Tsipras reaps benefits of brinkmanship politics

The state of the economy has always been a pivotal issue in electoral campaigns. Political commentators, spin doctors and journalists tend to agree with former US president Bill Clinton’s 1992 slogan: “It’s the economy, stupid [… that wins elections].”

Political scientists have tried to put this claim to the test. Despite the diversity in political systems and contexts, a stubborn empirical pattern has emerged: Incumbents tend to get re-elected in good economic times and voted out of office in bad economic times. In other words, positive economic evaluations help governments stay in office, whereas negative economic evaluations make it difficult for governments to stay in power.

The economy, thus, became the exemplary paradigm of what is known as “retrospective voting”: Voters form voting preferences based on their assessment of either the incumbent government’s overall macroeconomic record (“sociotropic voting”) or the impact of the incumbent’s policies on their own personal economic well-being (“pocketbook voting”).

Few elections have challenged this conventional wisdom more than the September 2015 election in Greece. The coalition government formed after the January 2015 election dedicated all seven months in office to the renegotiation of the country’s bailout agreement with its creditors. As the process dragged on without any agreement in sight – thus igniting fears of an impending deadlock – the primary surplus evaporated and the overall state of the economy deteriorated. The situation became even worse after the bank holiday and the imposition of capital controls. Still, the incumbent won what ended up being an easy landslide, seeing only infinitesimal losses in its vote share. How can one explain this paradox?

To answer this question, we commissioned a phone survey (fielded by the University of Macedonia and funded by the universities of York and Cambridge) with a random sample of 1,018 Greek citizens on September 7 and 8 (the election took place on September 20). The survey results reveal some interesting insights on how voters evaluated the performance of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s first government and why the government did not get punished in the election.

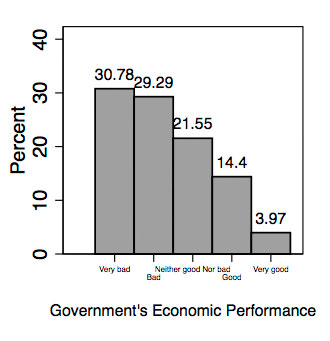

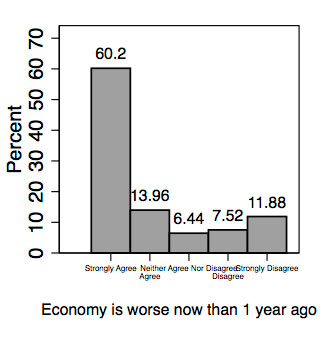

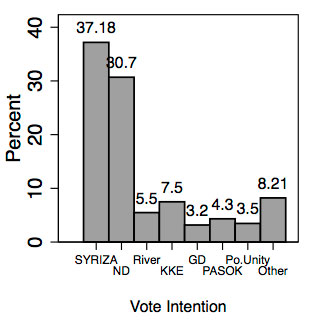

Before addressing this question, let us illustrate the puzzle. Voters re-elected a government which had avowedly had a disastrous economic record. Figure 1 shows three graphs. The first two confirm that the vast majority of respondents provide a negative evaluation of the government’s economic performance over its period in office. In the first graph we see that more than 60 percent of them characterize the government’s economic performance as either bad or very bad. Less than 20 percent of them gave a positive evaluation. The second graph shows that more than 70 percent of respondents believe that the economic situation had been better one year earlier. Finally, the third graph shows that, despite these negative evaluations, most respondents from the same survey declared their intention to vote for SYRIZA.

Figure 1: Economic evaluations and vote intention.

We believe that the explanation of this paradox lies in the distinction between effort and outcome. Effort here refers to how strongly citizens believed that the government had tried to achieve a positive result, whereas outcome here refers to the final agreement of the negotiation process.

Although the outcome was clearly negative, the Tsipras government repeatedly claimed that it was trying really hard to get a better deal. We argue that the government's electoral success is rooted in the fact that it was successful in distinguishing between effort and outcome and in deflecting the blame for the negative, growth-sapping aspects of the new bailout agreement to factors beyond its control, namely the intransigence of its creditors and the structural flaws of the eurozone. By assuming responsibility for the effort and attributing the bad economic outcome to institutions and agents operating at the European or even international level, it managed to escape the electoral defeat that usually awaits governments presiding over economic downturns.

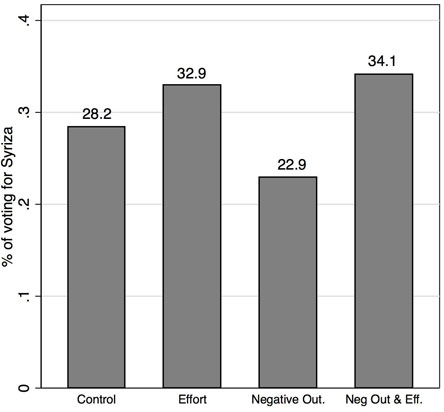

To test this claim, we designed a survey experiment. We randomly assigned respondents to four different groups. Apart from the control group, the other three received a statement (“cue”) about the government. In the first group, respondents received information about the government’s effort. It emphasized that the agreement was the result of a long and difficult negotiation process between the government and the creditors, but provided no information about the content of the agreement. The second group was informed about the negative outcome with a statement pointing out that the agreement would bring further austerity (taxes and expenditure cuts), but made no mention of the government’s effort. Finally, the third group of respondents received information about both the negative outcome and the government’s effort. The control group received no such prompting statement. After each of these preambles, respondents were asked how likely they were to vote for SYRIZA (on a scale from 1 to 5), the government party that assumed full responsibility over the negotiation strategy.

The results are shown below. The first column represents the condition with no reference either to the effort put in by the government or to the final outcome. It thus serves as a benchmark against which the other conditions can be compared. The second column shows how likely respondents are to vote for SYRIZA when emphasis is placed on the effort put by the government throughout the negotiation period (effort column). It can be seen that there is a substantial increase in the propensity to vote for SYRIZA as a reward for its effort. The third column, in contrast, shows that respondents are less likely to vote for SYRIZA when they are told that it achieved an agreement that prolongs austerity (outcome column). Finally, the last column of the graph suggests that, when effort is emphasized, pointing to the negative aspects of the agreement does not change things much compared to the standard effort treatment. If anything, it makes one even more likely to vote for SYRIZA. Our interpretation of these results is that the negative outcome signals both the difficulty of the task and the intention of the government to keep trying for a better agreement.

Figure 2: How vote intention for SYRIZA changes when thinking about effort and outcome.

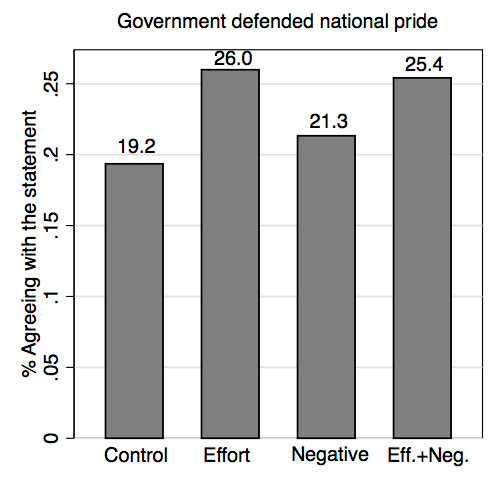

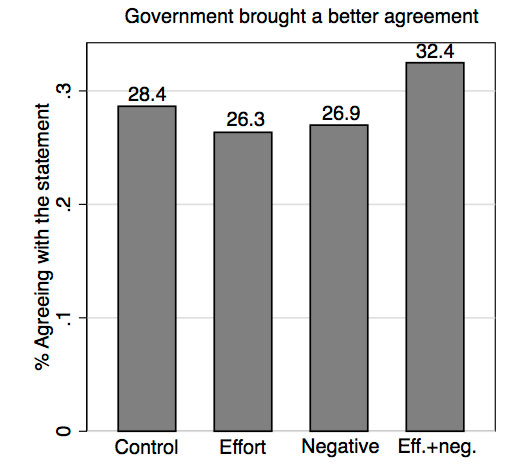

The same picture emerges when we look at more specific reactions to the final agreement. After the question on vote intention, respondents were asked to denote their level of agreement with the following sentences: “The government defended our national pride better than previous governments,” and “The government achieved a better agreement than previous governments.” Figure 3 below shows the percentage of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing with these statements.

We see that pointing to the negative aspects of the agreement does not make people more critical toward the government. On the other hand, pointing to the difficulty of the negotiation process makes people more favorable to the government and Tsipras in particular. Emphasizing that the government tried to improve conditions for Greek people in a very adverse environment seems to trigger two effects: Voters on average become more convinced that the government defended Greek national pride and that no better deal could have been achieved. This might help explain the increase in the likelihood to vote for SYRIZA described above. Finally, when both effort and outcome are mentioned, attention seems to be placed only on the former. Rather than causing a decline in the incumbent’s evaluation, reference to the introduction of new austerity measures seems to operate as yet another signal of how difficult the renegotiation task was and how committed Tsipras was to improving the conditions of the previous bailout program.

People did buy their core narrative, namely that they had fought hard to relax austerity measures for Greece. In fact, rather than driving down support, economic adversity seems to have served as a signal for the government’s resolve – after all, brinkmanship requires that one is actually willing to go to the brink.

Elias Dinas is an Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the University of Oxford.

Nikitas Konstantinidis is a Lecturer in International Political Economy at the University of Cambridge.

Also contributed to this report:

Ignacio Jurado, Lecturer in Politics at the University of York.

Stefanie Walter, Professor in International Relations and Political Economy at the University of Zurich.