The WWII plundering of a Jewish family’s property

Marios Sousis remembers a rather grim man – always well dressed in a white shirt and bow tie – making frequent visits to his family’s Athens home after the end of the Nazi occupation. A mere child at the time, Sousis could not know that this man was a lawyer – and his family’s only chance at reclaiming possessions plundered by acquaintances and neighbors after his father was shipped off to a concentration camp.

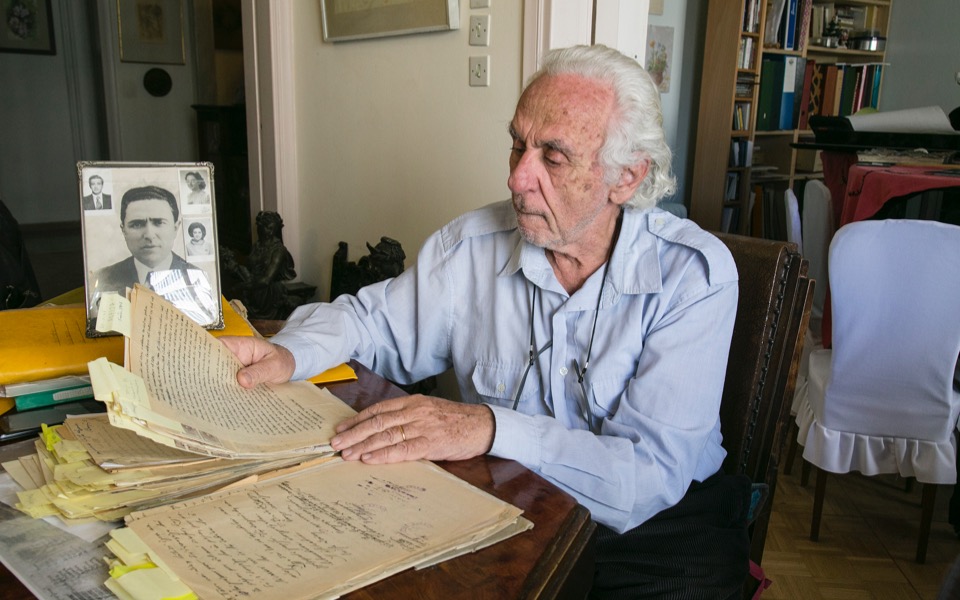

“My mother and I rarely discussed these subjects after the occupation. It was a past we wanted to forget,” says Sousis. “But she kept all these documents. Out of intuition, maybe? Who knows? They’re testaments of an era.”

He shows us a folder stuffed full of papers so fragile they look like they may disintegrate at a touch. His wife discovered them in a closet recently while spring cleaning: These yellowing papers are the case records of the trial against the plunderers.

These judicial documents, with dates starting a few weeks after the last German troops departed from Athens in 1944, provide a detailed description of the Sousis family’s tribulations. Close study also reveals how a section of society regarded Greek Jews during a turbulent time that brought out the best, but also the worst, in people.

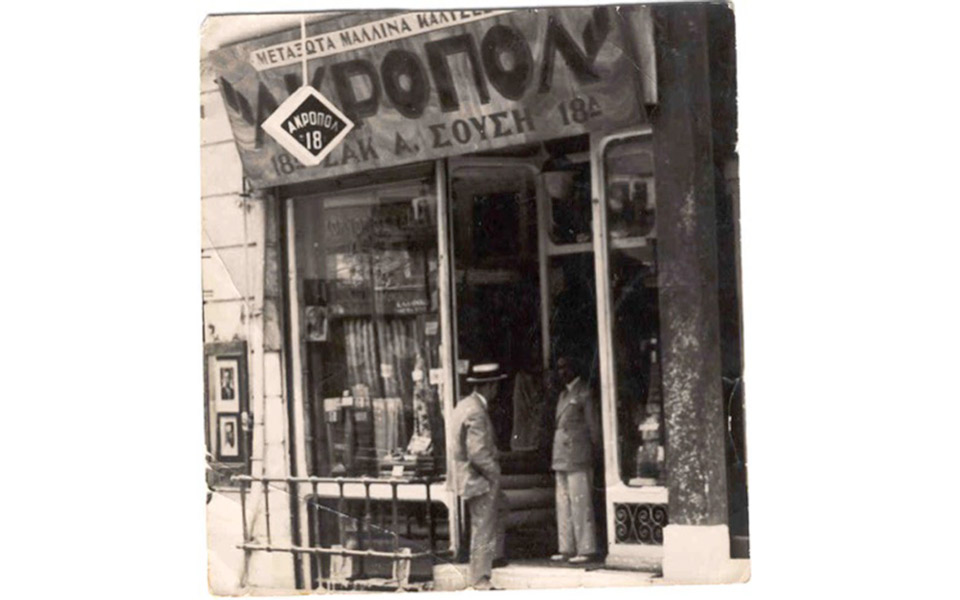

Before the arrival of German forces, the Sousis family’s store had for years been a fixture at 18 Ermou Street in downtown Athens. A simple glance inside showed why it was called Akropol: rows of replica Doric columns supporting shelves of silk fabrics and luxurious European coats.

As news started trickling into Athens about the persecution of the Jews in Thessaloniki, store owner Jacques Sousis decided to take action to protect his property. As his wife Louiza later testified in court, he decided to entrust his merchandise “until the calamity was over” to a neighbor who had a furniture workshop on nearby Voulis Street. In July 1943 porter Spyros Ionas admitted to transporting loads of silk stocking, coats and fabrics worth a total of 2,000 pounds sterling from the Ermou store to the Voulis Street furniture maker. The operation took four trips and Ionas took different routes each time so as not to raise any suspicions.

The Sousis family hid for a while with friends in the northern suburb of Halandri. At some point, Jacques told his acquaintance with the furniture shop that he wanted the Akropol merchandise back. The latter refused and, according to Louiza, threatened to turn the family in to the Nazi authorities. The Sousis family was planning to escape to Egypt, but never made it.

The court documents show that the furniture maker had a lengthy criminal record that included convictions for the kidnap, rape and attempted murder of a 15-year-old girl in the southern Athenian suburb of Glyfada, as well as embezzlement and escaping prison.

Despite the precautions he took, Jacques was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned with other Jews in Haidari, west of Athens. Knowing his life was in danger, he begged a fellow inmate, Raphael Paritsis, to find his wife and tell her to try to reclaim the merchandise. “Please. If I don’t make it, they will be destitute,” Jacques told Paritsis, according to the court records.

Paritsis was due for release because he had been baptized a Christian and was also married to one. But Sousis was headed to Auschwitz, where, according to records found by his son Marios, he was assigned to the “Special Command Units” – Jewish prisoners forced to take bodies from the gas chambers to the crematoriums.

“It was unconscionable, terrible. A man, a merchant minding his own business, looking after his family, being forced to burn bodies,” says Marios.

Jacques was tattooed with the number 182679. He didn’t make it back.

Later in court, the furniture maker denied all charges and even accused Jacques of gambling and owing him money. As his witness, he called another shopowner who had plundered the Sousis family’s wares and against whom another judicial proceeding was pending. The court was not convinced and in September 1945, the 48-year-old furniture maker was indicted to stand trial.

“From 1943, the Greek manifestation of Hitler’s curse began to show signs of a sadistic mania aimed at eradicating the ill-fated race to which Sousis belonged,” the judges wrote, rejecting the furniture maker’s testimony. They also added – relying on yet another stereotype – that Sousis could not possibly have owed large amounts even if he gambled “given his race’s fondness for money.”

They further ruled that it was unlikely Jacques Sousis had lied as his final words to Paritsis before he was taken to certain death were tantamount to a last will and testament to his wife.

The prevailing climate at that time is also evident in another part of the ruling: “The Israelites in question, with a quaking heart and aware of their fate, starting taking as many measures as possible to safeguard their assets and lives.”

The months passed but the defendants never faced trial as the case was settled out of court following a 1946 law aimed at easing pressure on the country’s overcrowded prisons that had brought the prosecutorial service to a standstill.

Jacques Sousis’s former employees did what they could to help Louiza, working at the shop without regular pay and taking home a part of the earnings from sales in a bid to get the business back on its feet. Nevertheless, in a country that was still in the grips of strife, their efforts failed.

After numerous setbacks, Louiza and later her children eventually managed to restart the family business, expanding it to new headquarters and into exports, and keeping it alive until the 1980s.

“I’m not bitter,” says Marios Sousis, closing the folder with the documents he plans to use to write a book. “It’s over. Now we must look ahead.”