Inspiring confidence, unafraid of cost

I came to Greece on leave from the International Monetary Fund in May 1991 to work for the Constantinos Mitsotakis government, which I believed could pull Greece out of the crisis. From my position as the prime minister’s chief economic adviser, I tried to contribute to this effort with the experience that I had gained in stabilization programs in my 11 years at the Fund.

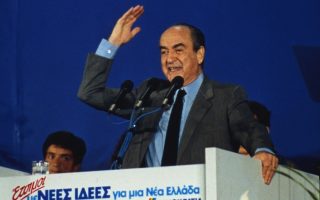

What I found in Greece was unprecedented, even compared to my experience in Latin America. Protest marches and rallies in downtown Athens against the economic policies being pursued were an almost daily occurrence. Molotov cocktails and stones being thrown at police and the destruction of public and private property were a matter of course. Newspapers ran the same headlines almost every day: “Tough days ahead,” “Hunger without end,” etc. It was in such a climate that the government was trying to bring some order to fiscal chaos and to liberate the economy from the bonds of statism, under incredibly adverse economic and political conditions. State-dependent business interests and labor unions fought it tooth-and-nail. It also faced opposition from within the governing party.

One of the first incidents I remember was the liberalization of the fuel market. Up until then, prices were set by the state and did not change according to fluctuations in the cost of imported fuel, meaning that consumers never got the incentive to save entailed by rising international prices. In one meeting at the prime minister’s office, all of the relevant ministers and agencies were present, and each was trying to kick the can to the other. Commerce Minister Andreas Andrianopoulos did not want the liberalization to be associated with price hikes. He asked Finance Minister Yannis Paleocrassas to absorb the increase in the budget by reducing the tax on fuel. Paleocrassas reacted forcefully, leading the prime minister to turn to the representative of the retailers and then to Vardis Vardinoyiannis, asking the refinery to absorb the price hike by reducing its profit margin. The answer: “Mr President, we’re only just getting by.” In the end, prices went up.

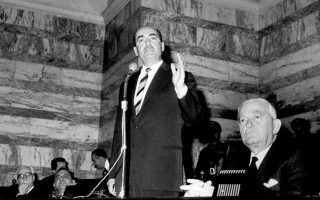

Mitsotakis inspired confidence. He spoke openly about all the issues, never made promises he couldn’t keep, was direct and honest. “There is no such thing as vested rights and fixed expenses,” he often told his ministers. He made difficult decisions that carried a political cost. Issuing two mobile telephony licenses to private companies, which ended OTE’s monopoly, and his attempt to privatize OTE were two such decisions. There were those in the government who were quick to express their opposition. “If asked, I will say I wasn’t present,” said the minister whose brief included OTE at the end of a meeting on the subject.

Toward me, Mitsotakis acted as a father, trying to get me acclimatized to Greek reality. “This isn’t New York, my dear,” he said when I suggested auctioning the properties of debtors to Ktimatiki Bank. “This one’s going to get us in line,” he’d tell his ministers about me in jest.

After I came back to Greece for good in 2011, I would meet with him regularly in his office and discuss the bailout programs. “You tell the troika that we sacked thousands of employees from the overindebted businesses that were managed by the Organization for the Reconstruction of Enterprises. You can’t have a smaller state without fewer employees.”

The Mitsotakis government realized that there was a large amount of government debt off the books. It began the painstaking task of tidying up public finances by issuing special “remediation” loans that increased public debt by 22 percent of GDP. This hidden debt stemmed from the forfeiture of guarantees granted in the 1980s, on debts of agricultural cooperatives and other businesses in which the Agricultural Bank (ATE) had a stake, as well as debts of state-controlled companies toward ETVA and other state banks. These efforts were completed as part of Greece’s bailout commitments in 2012-13, when ATE and ETVA were liquidated and their healthy assets were absorbed by Piraeus Bank.

There was also a lot of hidden debt from claims of the Bank of Greece on the Greek state, which appeared on the central bank’s balance sheet but were not included in the state debt. The 1992 Maastricht Treaty created greater urgency to properly account for these debts, as it prohibited the central bank from funding the government. The debts were settled with long-term treasury bonds and the practice of printing money to cover deficits was laid to rest. As Greece’s current representative at the IMF, Michalis Psalidopoulos, explains in his book “The History of the Bank of Greece,” this measure increased public debt from 88 percent of GDP in 1992 to 110 percent in 1993.

These measures increased the transparency of public finances and cleaned up the balance sheets of the banks and the central bank, while at the same time paving the way for Greece’s convergence with other member-states that wanted to join the eurozone. Steps were also taken to modernize and liberalize the economy that set the foundations for future growth. The biggest public works (the Athens metro, the airport at Spata, the Attiki Odos highway, the Rio-Antirio bridge) were designed by Stefanos Manos during the Mitsotakis administration, and attracted significant private capital and European funds. The social security reform of 1992, spearheaded by Manos and Dimitris Sioufas, staved off the system’s bankruptcy for decades. State-owned companies became limited liability corporations, allowing the state sell up to 49 percent of their shares. Taxes were reduced significantly, price controls were abolished and the lifting of exchange barriers was set into motion. If the Mitsotakis government had not been brought down prematurely, the country’s course would have been very different and bankruptcy could have been prevented.

* Miranda Xafa is a senior scholar at the Center for International Governance Innovation and a member of Drassi. She served as director of prime minister Constantinos Mitsotakis’s economic office between 1991 and 1993.