The journey and the sacrifice

Odyssey, tragedy, deadlock. The three words that sum up each of the chapters in Nikos Pilos’s 17-minute black-and-white documentary trilogy “Dying for Europe,” which makes its Greek debut at the ongoing Thessaloniki festival, have been routinely used by international media to describe Europe’s refugee crisis.

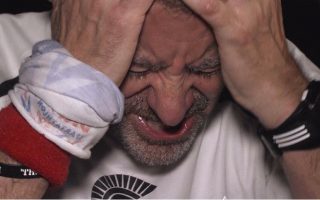

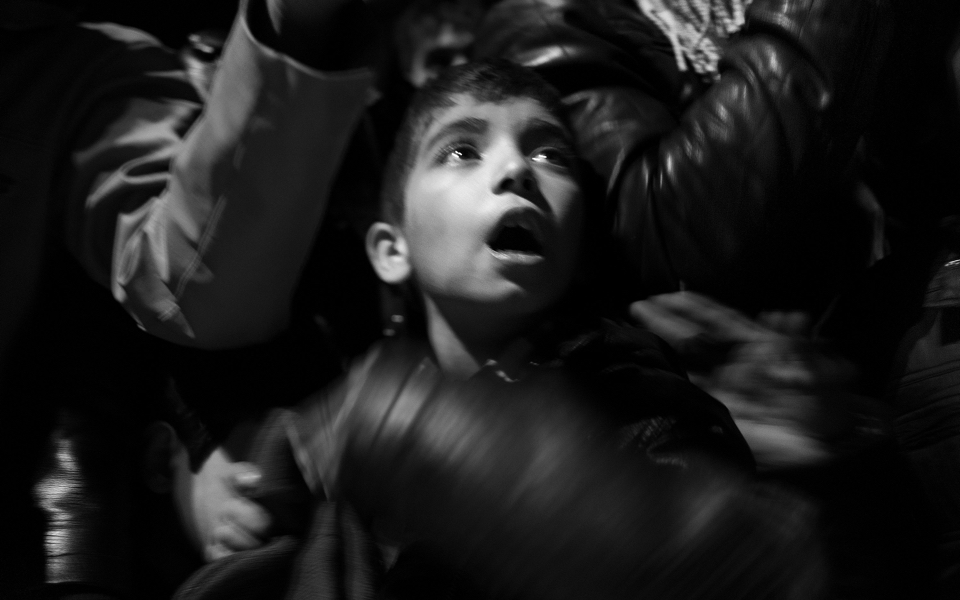

However, there is nothing cliche about the crisis itself. And this powerful and emotive film lays bare the harrowing reality of displacement in a way that inevitably makes the mind cling to the project title’s eerie, literal interpretation. When the boat carrying Youssef Hamo and his family sinks off the eastern Aegean island of Kos, the 56-year-old Syrian refugee has to grapple with the loss of his wife, son and daughter, while another son is missing.

Shot over a period of eight months, the short chronicles the perilous journey of the wretched masses, the tragedy of loss, and the eventual closure of the so-called Balkan route that left thousands of people stranded on Greek soil.

Yet although human suffering is the dominant element in the whirling vortex of Europe’s refugee crisis, it is not the only one. Kathimerini English Edition caught up with the award-winning photojournalist for a discussion on the personal and professional challenges that come into play in documenting a theme where ethical, humanitarian, political and aesthetic issues intersect.

Born in Athens in 1967, Pilos has over the past three decades documented conflicts, natural disasters, poverty and cultural shifts across the globe, including the overthrow of Romania’s communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, the breakdown of former Yugoslavia and the Iraq war.

His work has featured in major media publications including The New York Times, Time, The Financial Times, and The Guardian. It has also brought him numerous awards, most recently second place in the 2017 World Press Photo Digital Storytelling Contest's Short Form category for his film “Trapped,” on the shutdown of the Balkan refugee route to Northern Europe.

Although coverage of the refugee crisis has brought Pilos closer to home, the stakes, he says, are nothing less than the very survival of European values.

What compelled you to explore this subject? How long did the project take and what was its goal? What does it add to an issue that has been so widely discussed already?

I was driven by the fact that members of my family and close circle have emigrated and I still have relatives in America. I have been interested in this subject since the 1980s, when thousands of refugees from Eastern Europe came to Greece looking for a better life. I dare say we did not treat them in the best possible manner.

The project was shot over a period of eight months and addresses the question: What does someone need to sacrifice to reach Europe? The answer is given by the survivor Youssef as he describes his family's deadly journey from the Turkish coast to Kos frame by frame. The narrative closes with the fence placed on the border between Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, effectively closing the Balkan route and the path of thousands of refugees to Europe. Trapped behind the barbed wire, they unwittingly become the symbol of a modern version of isolationism, nationalist fervor and xenophobia.

Even though the timeline follows that of the Balkan route, it describes the overall collapse of united Europe's values.

What kind of psychological impact can such a project have? How easy is it to compartmentalize it and not take it home with you?

Of course there is a lot of psychological pressure in situations like this, pressure that freelancers like myself have to deal with on their own or only with the help of their close environment, unlike people who work for major agencies that give them all the help and support they need in the field and later. When you've been doing this for years, there are no compartments. You just learn to cope.

Is it possible not to become personally involved in this kind of work?

Learning how not to become personally involved is a lengthy process that comes automatically as time goes on and you mature professionally. It is also the factor that helps you limit the psychological pressure and allows you to record the events around you objectively.

Which moment or scene has had the biggest impact on you?

There are so many but in this particular project what really shocked me was the stoicism of one of our documentary's protagonists, Youssef, toward the loss of his family in the Kos wreck.

How do you respond to criticism regarding graphic images like those of the Kos wreck? Are there instances when the victim, their families or viewers need to be protected? Can constant exposure to such images lead to compassion fatigue in the public?

To begin with, let me say that I disagree entirely with the term graphic images. If you look at the global coverage, it was images such as these that influenced public opinion and changed the course of events on a number of issues. I can cite many examples, starting with the photograph of the toddler Aylan on the beach of Bodrum. Or a Greek one from in the inter-war years in Thessaloniki showing the mother of a tobacco worker mourning over her son's body lying on a door, killed by a police officer during a tobacco workers' protest, a photograph that inspired one of the greatest pieces of modern Greek poetry, Yiannis Ritsos's “Epitaphios.” Or the world-famous photograph of the young girl running away from a napalm bomb in Vietnam that helped change the course of the war. Or that from Biafra of a vulture waiting for life to leave a bloated half-dead boy so it can devour him, which galvanized the United Nations into action. Or the photograph by Robert Capa of a democratic army soldier dropping dead from a bullet in the Spanish Civil War. And hundreds more.

I want to stress that this conversation started in the mid-1990s when businessmen replaced traditional media publishers. This resulted in content being more or less determined by advertisers who did not want to see such material next to their ads.

Naturally such images need to be published with caution, but I do not believe that they weaken the message. The message can be so strong that the US government prohibited the publication of images of dead American soldiers in the last Gulf war. It took three before The New York Times, I believe, flouted the ban and directly opposed the Bush administration.

There are, of course, many cases where the victims and their relatives need to be protected. I will agree that there is no reason to publicize the photograph of a car crash victim, but I would not say the same of the photograph showing [slain rapper] Pavlos Fyssas in his girlfriend’s arms shortly before he died. This was a historic event and not only should it have been published, but the photograph should serve as the main image in any march against fascism, refreshing the memories of older members of society and teaching the young ones.

In the case of the Kos shipwreck, the material was published with the surviving father’s approval.

Do you find yourself facing moral quandaries in this line of work? Is it odd to present such an ugly subject in such a “beautiful” way?

I started out in the 1980s, at a time when the media had full access to all social and political developments. There were no privacy laws, so, perforce, you had to set the limits on what was morally acceptable and what was not. It’s still a constant process.

What we are looking at here is not a spectacle but reality, and each individual has the choice whether to watch or ignore it. As for the artistic aspect, this is a matter of each photographer’s style.

Were you inspired by a particular project for this film and why did you opt for black-and-white?

Filming in black-and-white was intended as a response to the ephemeral. Images of the refugee crisis that were shown time and time again on news bulletins and others that were buried in the miscellaneous file serve as the threads of a narrative that has escaped the confines of a classical news feature and aims at sending a powerful political message to united Europe, a notion founded on the principles of open borders and democracy.

What do you do that is different to other photographers? What are the dividing lines between photojournalism and other related forms like documentary filmmaking?

I don’t think I do anything different to my colleagues. Technology is giving us new means of expression and it is only natural to use them – this is what evolution is about, after all.

I also don’t see that there are any differences between photojournalism and documentary filmmaking. It is the same narrative in a different medium. As a photojournalist you are looking for a moment and as a documentary filmmaker you want an entire scene to tell the story. Photography and documentary film are arts that were created to reach out to a broad audience and this is precisely what photojournalism and documentary filmmaking do.

Can they bring change or are they simply preaching to the converted? Is the onslaught of fake news a defeat for documentaries?

I don’t believe that viewers have had an overdose of tough images.

The difficulty of a photograph changing something in the present doesn’t have to do with who takes it but with the fact that mainstream media, mainly, are losing their credibility and therefore have shrinking influence. In the age of social media, of course, a message can reach a lot of people in a lot of different ways.

I also don’t believe that fake news influences or is a blow to documentaries. After all, it is as easy to expose a fake photograph as it is to manipulate an image with digital technology. Also, most fake news is exposed for what it is within a very short period of time.

“Dying for Europe” | Crew: Director: Nikos Pilos, Second Unit Camera: Arsinoi Pilou, Iraklis Demertzidis, Giorgos Grilis, Script: Natasha Blatsiou, Video Editor: Pantelis Liakopoulos Music Sound Designer: Orestis Kaberidis | Screenings: Frida Liappa Theater, Wednesday, March 7, 8.30 p.m. and Pavlos Zannas Theater, Friday, March 9, 12.45 p.m.