Short-story writer George Saunders makes thrilling foray into novels

Getting out of a pair of handcuffs was one of Harry Houdini’s oldest tricks. In 1904, during a performance in London, the illusionist was manacled in a pair on which a blacksmith had spent five years perfecting the locking mechanism, claiming “no mortal man” could pick it. It took Houdini more an hour and 10 minutes to get out of them. As he was held aloft by a roaring crowd, the master of escape wept.

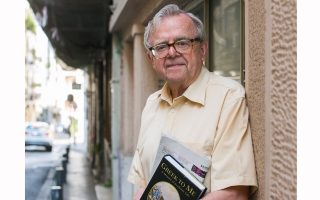

American short-story writer George Saunders often references Houdini for the fact that he constantly set himself tougher new challenges. “As an artist, the difficult thing is to think of new tricks – old tricks won’t work,” says Saunders, whose latest book, and first novel, “Lincoln in the Bardo,” was recently published in Greek by Ikaros.

Having earned Saunders the 2017 Man Booker Prize, “Lincoln in the Bardo” is a thrilling, touching and humorous exploration of life, death and the state of limbo, which unfolds when the American president visits the grave of his 11-year-old son Willie.

As he was writing it, Saunders often felt like Houdini himself. “Historical novel (mmm), Lincoln (mmm), death of a child… it’s like I’m saying, ‘I’ll write a novel from the point of view of a chicken,’” he told Kathimerini.

Like most things in his life as a writer, the 59-year-old started with the obstacles: “When I start a project my mind lists the problems first, (such as) that could be bad, corny, difficult – and that’s when you know you have a project. I was really worried about it but at this point of my career the danger is that I won’t be worried.”

Saunders was born in Amarillo, Texas, in 1958, and has a Greek connection on his great-grandfather’s side. He grew up on the outskirts of Chicago in a family with a great sense of humor and crazy stories. He studied engineering and worked briefly for an oil company that sent him to Indonesia. He had never been outside the USA before university and travel had such a radical effect on his view of the world that he shifted from the conservative to the left of the political spectrum. Then in 1986, at the age of 28, he was accepted into Syracuse University’s program of creative writing, where he had Tobias Wolff as a teacher and mentor.

Sipping on coffee out of a paper cup and dressed in a dark short-sleeved shirt and black trousers that he kept hitching up after forgetting to pack a belt, the writer was in Greece to deliver a talk on the occasion of Athens being 2018’s World Book Capital when he met with Kathimerini. Full of nervous energy, he talked about his days at Syracuse, his admiration for Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Carver, and his initial ideas of what a writer should be.

“I had a young man’s idea that a writer should be tough, drunk, uncompromising, and Toby was none of those things,” he said of Wolff. “He’s tough, but sweet, and I just watched him with his family, how he came in and did a beautiful class, wrote beautiful stories, and there was something about that which was liberating. You could be who you are. If you are a nice person be a nice person. I don’t have to behave in a certain way, live in a certain way or be at war, I just have to have a mind that’s original.”

Saunders now teaches creative writing at Syracuse in a program that takes just six of some 650 applicants a year. We asked him why short stories are so popular among American writers.

“We like to think of ourselves as being pragmatic and there’s an anti-intellectual tradition in America. So a young American writer is maybe less comfortable than other writers at having a big thematic intention. Maybe because they aren’t very well educated,” he said. “But they are pretty comfortable in the Hemingway-ish tradition, making something small and beautiful and then letting the truth pop out of that.”

Saunders is widely considered among America’s greatest short-story writers today, yet he doesn’t like to bother with the “big issues.”

“Writers like [Philip] Roth go in through the front door and change the house. I kind of come in through the basement window and f**k around in the basement. I tend to be a house thief: I look at the house and say, ‘Hmm, which window can I get in?’ I think I have something to offer in terms of class. I have written about it and I will write more because I think it’s very important and it’s been neglected,” he said. “I play a different lower game here. But I think if I play my different lower game passionately, I might be able to contribute something.”

The big issues come into play once he starts writing, though, asking himself questions he doesn’t know the answers to. So, in “Lincoln in the Bardo,” Saunders explored issues that are at the heart of American society, like slavery and racism, including in his narrative the voices of slaves interred in a mass grave.

“For this book I thought, ‘Slavery, no, that’s too hard.’ But then you are in a graveyard in 1862 and Lincoln comes in – you need some black voices in there. Then it becomes mechanical: They are not allowed in the graveyard. They are fenced in, why? They are in a mass grave, why? Suddenly you have all their stories. If you start the process and resolve to be honest, the world will flood into your book whether you want it or not,” he told Kathimerini.

Abraham Lincoln is a lot like Jesus in America’s political history, a figure who is known throughout the world for his role in the Civil War, for the abolition of slavery, for modernizing the American economy. The death of Willie, his third son, marked Lincoln, who visited the boy’s grave alone shortly after the funeral. The idea of writing something inspired by this tragic event had been in Saunders’s mind for some 20 years.

“There’s kind of a moment of truth, seeing that you’ve been resisting it because it’s difficult. That’s not good; that’s the end of your career if you do that,” he says. “But I’ve learned to trust a certain feeling of dread. It’s like when you see someone really beautiful and you want to talk to them and you are terrified. It’s a good feeling.”

The novel’s publication coincided with Donald Trump’s election as US president and while Saunders was worried that it would be regarded as overly patriotic, it actually helped readers see Lincoln and America in a different light. “You could feel people thinking like, ‘Look at this beautiful thing we had, we took it for granted and now it is changing so much.’”

Loss and grief are powerful themes in the book and when asked whether writing about death helped him come to terms with the notion of mortality, Saunders replied, “Only because it hasn’t happened to me!”

Saunders readily admits that there’s a lot he’s not at peace with. “I’m very neurotic, very nervous,” he said.

“As I get older I’m very aware that even if – God willing – I make it to the end of my life as it’s gone so far, without terrible losses, some health, some accomplishment, it’s just luck. You didn’t earn it,” Saunders said.

“The corrosive idea of American capitalism is that if you have a nice car, you earned it, you are a good guy, and if you don’t, it’s your problem. There’s no mercy in that, there’s no sense that everything can happen to anybody,” he added. “It’s in our politics too. If you are unfortunate, there is a sense that it’s your problem.”

Saunders, who recently turned to the teachings of Buddhism, was raised a Catholic, believing that “part of your power as a person was your mercy,” and finds the Trump presidency’s “America first” motto somewhat frightening.

“That’s a terribly thin thing to believe in. The ideas that should be behind that, of humanity and kindness and spiritual values, those aren’t there. And I don’t mean just Trump – the whole government is that way. So that doesn’t make it much of a culture.”