Urban explorer weaves a fresh narrative for Athens

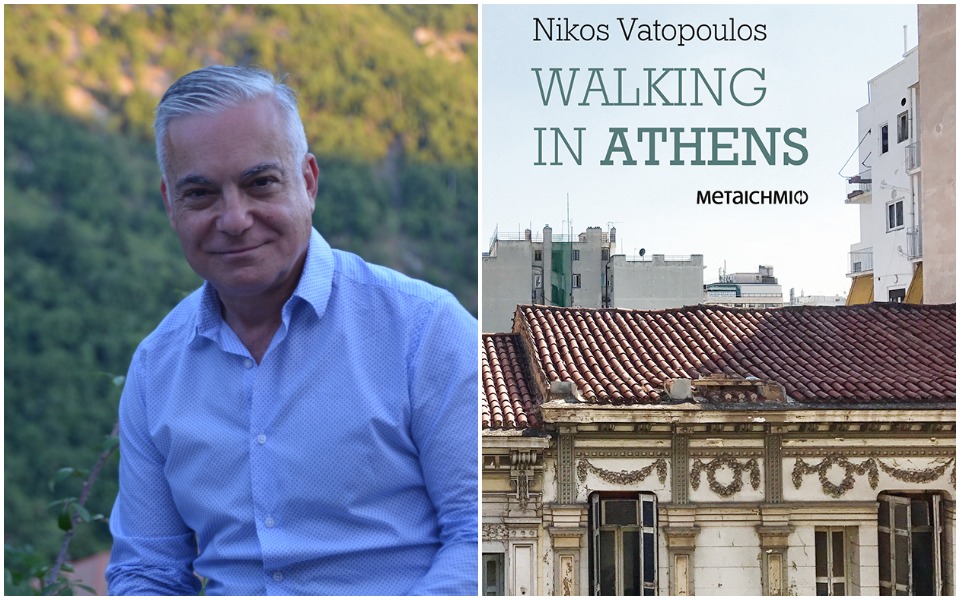

Defined by Athens, Nikos Vatopoulos has certainly worked hard to give something back to the city where he was born and raised. His prolific work as a journalist, writer, amateur photographer and urban activist has influenced contemporary perceptions of the Greek capital.

Vatopoulos would be the first to agree that Athens is not by any measure endowed with the picture-postcard beauty of its European counterparts. Fraught with contrasts and contradictions, this sprawling metropolis resists any straightforward classification.

“I used to be a staunch aesthete, offended by Athens’ shortcomings,” Vatopoulos says. “But I have since broadened the criteria by which I consider something beautiful or ugly. I am interested in what is interesting and in why something is there in front of me and in whether there is a way for it to go away if it bothers me,” he says.

The shift seems to convey a quasi-existential understanding that the aesthetic and cultural mess that is Athens needs to be embraced if one is to ever feel comfortable here. It’s an admittedly more mature and pragmatic outlook, more in line with the ideal of a city as a living system, a constantly changing whole that resembles an incubator of narratives and emotions such as those captured in his latest book, “Walking in Athens.”

The 181-page volume, recently published in English by Metaichmio (translated by Joshua Barley), is a collection of articles written for Kathimerini newspaper where Vatopoulos works as cultural editor. Vatopoulos, a keen-eyed street wanderer-turned-archaeologist of the present strolls the capital’s emblematic boulevards and meandering backstreets documenting robust and humble buildings, neat houses and crumbling ruins. In the process, he chronicles the succession of human lives, cultural changes and civilizational shifts. It is a gentle albeit thoughtful exercise.

Born in downtown Athens in 1960, Vatopoulos moved toward adulthood as the city’s urban and social transformation was in full swing. It was a highly optimistic period which however bequeathed the capital with a controversial architectural legacy (though one that the writer does not shy away from). Now standing at what appears to be the close of Greece’s brutal 10-year crisis, Vatopoulos refuses to give up his optimism about Athens. The financial meltdown has naturally left deep scars on the urban fabric, yet it has, at the same time, impacted the urban mind-set in a positive manner.

“The new generations that come to the fore will come to see this crisis – with the worst of it seeming to come to a close after a 10-year cycle – as a major rift in the city’s evolution,” he says. “It is important not just because of its absolutely obvious downward spiral but also because a large part of the residents of this city redefined their relationship with the urban environment.”

What compelled you to write these pieces? Was it a quest for a beauty or the desire to make a record of things that are being lost?

It was mostly an effort to understand this city, I would say. Even though I was born in Athens, grew up in Athens and my entire life is intrinsically linked with this city, I always felt there was room for me to go even deeper in understanding how it has been shaped and what makes it tick. I suppose that curiosity was my trigger, an enormous amount of curiosity about Athens, which obviously comes with an enormous amount of love. I want to understand it because I love it, so I think that this article series was the next stop in my relationship with Athens. I wrote about more obvious subjects in the first few years, but the series later led me to discover the unseen city – that is what interested me most; locating those reserves of a bourgeois culture (note: Vatopoulos uses the world “astiko,” which he defines as a kind of bourgeois, metropolitan culture, but without the baggage of class) that are usually not so apparent. If you don’t go looking for it, this treasure won’t just appear of its own accord. And I believe that Athens has a stock of buildings that basically illustrates its cultural evolution and is right there; we just have to see it to incorporate it into the city’s greater narrative. Athens’ modern story is enough for me; I am very interested in it.

In your book you talk about a new watershed in the city’s history: before and after the economic crisis. Do you believe this outlook will prevail in the future?

I do. I believe it has been a major watershed. I am part of a generation – like many other generations, of course – that has been defined by 20th century milestones. I believe that as the events of the 20th century move into the past, the new generations that come to the fore will come to see this crisis – with the worst of it seeming to come to a close after a 10-year cycle – as a major rift in the city’s evolution. It is important not just because of its absolutely obvious downward spiral but also because a large part of the residents of this city redefined their relationship with the urban environment. This is the important part, the psychological shift. And this, of course, has left a mark in the form of neglect. But apart from this, I believe the crisis gave the city space for a new beginning and in this regard I am somewhat optimistic about its prospects.

Where does that optimism come from?

Well, it’s partly who I am as a person, always positive and open to things, but I do believe that there is a critical mass of young residents that care about this city. Even those who cannot invest in the city in any way – be it economic, educational or in some other way – are ready to be useful as citizens. This may not be visible yet, but there is a greater proportion of mostly young people who want to be part of the city’s evolution than there was in the past. They also have a much sophisticated point of view.

What would be the glue to keep this city together – if it even needs such a thing?

Abolishing stereotypes, re-establishing the notion of Athens in a way that entails civic pride and inclusiveness. I believe that there needs to be plenty of social space in the new narrative for Athens; space for identity-shaping and for the city’s residents to redefine themselves. It is futile to approach Athens in terms that belong to the 1990s; it is unrealistic. Athens needs to develop a metropolitan identity, but with social cohesion – that is the most important thing.

Speaking of cohesion, is the absence of aesthetic cohesion a boon or a bane for the city?

I have vacillated in this regard. I used to be a staunch aesthete, offended by Athens’ shortcomings, but I have since broadened the criteria by which I consider something beautiful or ugly. I am interested in what is interesting and in why something is there in front of me and in whether there is a way for it to go away if it bothers me. On a recent tour of Neapoli and Exarchia I made an unplanned stop in front of two buildings from the 1980s that are, objectively, extremely ugly. I told my group: “Observe these buildings, because they too are a part of Athens’ reality. In order to understand Athens we need to also make room for them in our minds.” This is regardless of whether we like them or not, but this is an entirely different conversation.

Do you think that Athens struggles under the weight of its history? Does it need a new identity in which its Classical heritage is simply a part rather than a symbol of unattainable heights?

I believe in Athens’ continuum and I think it has been very bad for the city that new Athens has been cast as the result of the “darkness of the Turkish occupation,” a chasm that is nothing more than a notion, a construct of the modern age that rejected centuries of the Ottoman era (calling it post-Byzantine no less – another outrage) and which completely overlooks the period of Frankish rule (I bet only a handful of Greeks know that Athens once had a Catalan administration), etc. There is, however, a very interesting trend toward seeing Athens as a historical continuum, from the pre-Classical age to the present day, with fascinating peaks and troughs, of course, and all of which contributes to what we see and mainly to what we feel about Athens.

What gives you greater pleasure: a new, beautiful structure or the restoration of an old one?

I have never thought about it. I will say the former; the construction of a beautiful new thing. This is the greatest vote of confidence you can give to a city’s future. New beautiful buildings mean that people are envisioning their lives in this city in a much more succinct way. By no means do I dismiss the latter, though.

Which is your favorite Athenian street?

Patission. It may be because I grew up there, but I think that it exemplifies Athens’ urbanization in a very distinct way, while it also gives me this combination of joy and sadness.

Do you feel uncomfortable when you see a tourist walking around the “wrong” parts of Athens? What is this city’s biggest problem?

I used to, yes, quite profoundly. I am more relaxed about it now. But I also think that a lot of foreign tourists have changed too. I see many – and I don’t mean the mass tourism lot that’s obviously here just for a good time, which is also fine – who are interested in what is going on around them, who are not looking to stay in their comfort zone or for the obviously beautiful. I recently saw two tourists who weren’t lost walking along Liosion Street – they were having a wander and the look on their faces was very interesting.

Has any particular urban regeneration project from among the many that are put forward every so often caught your attention?

I believe the Rethink Athens project really should have been carried out. I think it would have helped Athens, added a lot of trees and fixed Omonia Square, which is a major issue. We Greeks are very swift to say no and very reluctant to sit down and talk.

Nevertheless, I read that the new mayor invited you for a discussion about the city. Did you make any suggestions?

Yes, we had dinner, but it was part of a busy schedule of many meetings with Athenians. What I told him – and he appeared interested in the idea – was about rooftops, which also have to do with the climate and with the city’s appearance. I think it’s a major issue. If you look out at Athens from Lycabettus or the Acropolis, you see that there has been no thought given to how rooftops could contribute aesthetically and ecologically. The many options provided by technology (you can have swimming pools, gardens, new-tech tiling, etc) in combination with incentives and tax breaks could transform Athens completely within five years.

You have already published dozens of articles, books and albums, organized exhibitions and founded the now-defunct Saturdays in Athens urban activist group, all about the capital. What else can we expect?

I want to keep writing books. I’m working on one now that will be published this fall, again by Metaichmio, which is my take on 23 Greek cities, an essay on the country’s undervalued urban space. I am an amateur photographer and would like to have a show, while I would also like to write a big book about Athens that would be about the city and people from my generation, about buildings and books, people and movies.