Historic neighborhood caught up in red tape snarl

Like her mother and grandmother before that, Anna Gerardi was born in Anafiotika, the picturesque neighborhood on the northeast side of the Acropolis hill. Her great grandfather has bought the tiny house, Number 29, in 1906 from the man who had built it.

Measuring just 29 square meters, it basically comprises one room that has been separated into two areas and a tiny kitchen annex, with a small bathroom tucked away behind a curtain. As a child she would hear how the original owners of the homes in the little neighborhood chose to live on the Acropolis because of its resemblance to the castle hill of their native island, Anafi, and were able to do so after being given the green light from King Otto.

Gerardi recently decided to make a few minor improvements to the property before passing it on, in turn, to her son. She went to the Archaeological Service to get the necessary license, only to be informed by an employee there that she did not formally own the house. “You should have moved out years ago,” the employee said.

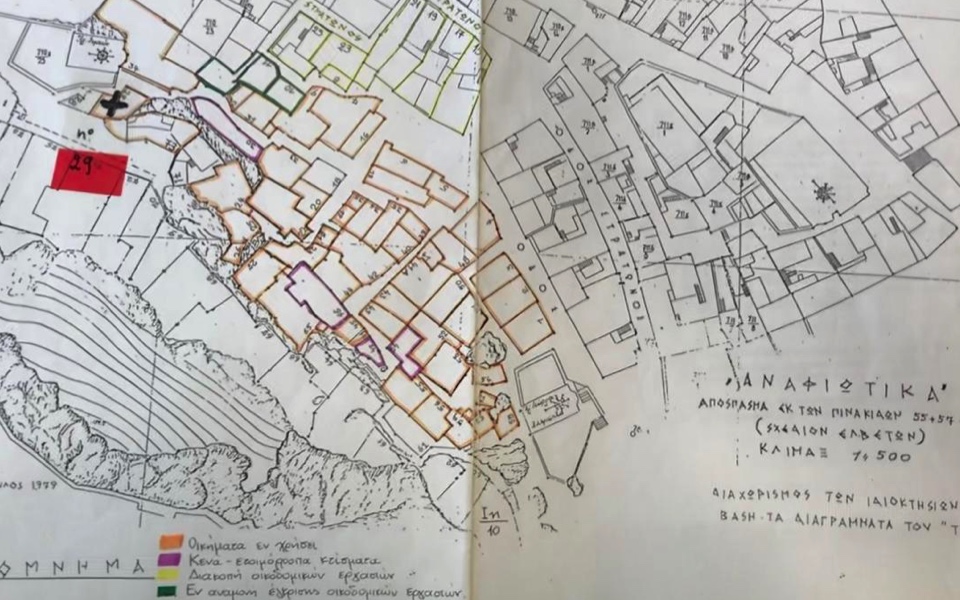

Gerardi was shocked. She knew that the property’s legal status was vague, but she had the purchase contract from 1906 and the inheritance contract from 2013, when her mother died. The titles had been transferred at the records office and she paid property tax regularly. None of this, however, was as clear as it seemed because her home, along with another 74 properties in the area, had been expropriated in 1973 and now officially belong to the Greek state.

Kathimerini was granted access to the Culture Ministry’s files on the neighborhood, finding hundreds of documents that tell the complex tale of one of Athens’ most popular tourist spots and shed light on the state mechanism’s inability to manage the area.

Anafiotika’s first homes were built during King Otto’s reign in 1832-62 by builders from Anafi tasked with constructing the palace and other royal buildings who could not afford the cost of living in the expensive city center. They pooled their resources and built the first cluster of homes together, usually at night so they could sidestep various laws. The authorities initially condemned the emerging neighborhood because it was within the archaeological zone surrounding the Acropolis.

The records show numerous complaints from state authorities saying that the neighborhood was an affront to the ancient citadel above it. But with Greece being notorious for allowing temporary things to become permanent, the 80 small houses that comprised the neighborhood managed to survive for more than a century, maintaining the social homogeneity. Even though the fear of appropriation was a constant in their lives, the owners always regarded it as something that would happen “in the future.”

They first heard of the state’s plan to take ownership of the properties in 1967, when one of the owners applied for a license to add a window. Eviction notices were sent to all the owners over the next few months and they were told their compensation money was waiting for them at the Deposits and Loans Fund. Nine houses were spared – whether by mistake, good fortune or design, no one knows. Many owners, including Gerardi’s parents, decided not to cash in their compensation payments in the hopes that this would halt the appropriation process. That didn’t happen, of course, and they lost their right to claim the money.

The ministry’s initial plan was to demolish the row of houses nearest to the top of the Acropolis in order to free the ancient path up to the citadel. Ten owners handed over their keys and left, but the remainder refused to budge, citing different reasons: “They claimed old age or ill health, others swore and blasphemed,” wrote the civil service employee tasked with trying to reason with them. It took six years for that first row of houses to go – and another 20 for the ancient path to be opened.

The remaining owners knew that it was just a matter of time before their homes went as well. They launched a campaign to save them, with the support of the Athens University School of Architecture, the National Technical University of Athens, several prominent politicians, journalists and others.

Georgios Dontas, who served as the director of the Acropolis from the late 1960s to the early 80s, also defended the drive to save the rest of the neighborhood, saying that the top row of houses was the only one that really had to go. He wrote in a memo that the surviving homes were a “monument of vernacular architecture and their loss would be a blow to Athens.” His vision to have Anafiotika listed for preservation and restored never materialized.

The newcomers

Over the next decades, every change of leadership at the ministry would trigger a new round of debate about the future of the surviving houses. Teams were sent out every so often to knock on doors and record who lived where. Some of the houses were abandoned by their owners, others acquired new tenants. There was an architect, for example, who had rented a house from its previous owner in 1979. He loved the property and took excellent care of it, making repairs when needed despite several oral and written objections from the Culture Ministry.

In a letter to the authorities, he explained how he stopped paying rent once he found out that the property was actually owned by the state. But he did not move out. He stayed and took an active interest in the Anafiotika’s fate. He later wrote a letter to the ministry thanking it for allowing him to live at the foot of the Acropolis. “The house will be delivered to you at some point in the future, intact and restored, so long as it is not slated for demolition, something that I deplore and, as a citizen of Athens, would fight,” he wrote.

The ministry’s records contain dozens of appeals from foreigners and Greeks asking to be allowed to live in the empty houses. The area’s residents also received dozens of similar appeals, usually as notes slipped under their doors, from tourists, students and artists, but also architects and civil engineers keen to study the architecture from up close.

The official response to efforts to take over the houses was mixed. Sometimes, for example, the ministry would actively try to evict squatters; at others, it would let them stay on, on the condition that they paid a squatter’s fee to the Archaeological Fund (it came to 5.93 euros every three months). One internal Culture Ministry memo admits that the situation with the squatters was putting the authorities in an “extremely difficult position (…) given that we are responsible for the space but cannot intervene to restore order.”

The situation also angered a number of the former owners, who saw the squatters as audaciously benefiting from the authorities’ callousness, and appealed to the ministry to cancel the appropriation. The documents reveal that this option was discussed at some point but was rejected on the grounds of “safeguarding the state’s reputation.” Subsequent requests by the former owners have been turned down, though without any explanation of what is to become of Anafiotika.

The fact is that whatever purpose the appropriation was intended to serve has had 47 years to transpire. In the meantime, the constantly dwindling number of owners and squatters, some 40 altogether, continue to take care of the buildings and their surroundings on their own, without any contribution from the state.

An abandoned construction site at one end of the neighborhood serves as a constant reminder of what the people of Anafiotika can expect from the state. It was, ironically, supposed to become a museum on life in Athens, located on the site of seven demolished houses. Construction on the project started in 1996 and was abandoned within a few months as it did not have the necessary licenses.

The Central Archaeological Council pulled the plug on the project in 1998, but the site was never cleared and is not only an eyesore seen by thousands of tourists every day, but is also a health and safety hazard. A memo warned as much after inspectors were sent to the site a couple of years ago, who described it as a “breeding ground for insects and rodents, with negative effects on the health of residents and passers-by.”

A few lackluster efforts to clean it up have been made over the years, but the Culture Ministry appears unable to carry out the task. The cost, sources tell Kathimerini, is prohibitive.