Remembering the Spanish flu, a century later

It was a Sunday night a few weeks back and Marianna Theodoropoulou kept looking at her watch. She was determined to be on her balcony at 9 p.m. sharp to applaud the country’s hospital doctors and nurses battling the coronavirus crisis. “I had a personal reason, apart from the gratitude I wanted to express,” she tells Kathimerini. Her grandfather, Georgios Gavalas, was a doctor who died treating patients of the Spanish flu in 1918, and her applause was for him as much as for today’s frontline medical workers.

She grew up listening to stories about her grandfather and remembers her grandmother showing her treasured items like his medical degree from March 2, 1901, and a faded sepia photograph of the elegantly lanky young man with a faraway look in his eyes. The stories haunted her. “I never could have imagined that we’d be experiencing such a similar situation a century later,” says Theodoropoulou.

Tzortzis, as he was known, was born in the village of Emborio on the southern Aegean island of Santorini. The youngest of five in a family of grape farmers, he managed to attend medical school in Athens and returned to the island to work as an obstetrician and gynecologist.

“He traveled to the surrounding islands a lot to visit patients and met my grandmother Maria in Anafi. They fell madly in love, got married and moved to Athens, where my mother was born,” says Theodoropoulou.

Two years later, in the summer of 1918, their lives were turned upside down as the Spanish flu made its first appearance in Greece in late July. While the situation at first seemed under control, it deteriorated rapidly over the course of a few months. When Tzortzis was called on to help, he accepted without a second thought. He threw some clothes into a suitcase and said goodbye to his toddler daughter and wife, instructing her not to leave the house unless absolutely necessary, to wash her hands diligently, to change and wash her clothes often and to treat the smallest of symptoms with antiseptic gargles and inhalations – the only known response at the time. He was assigned to a field hospital in Oropos, eastern Attica, which had been set up after facilities in Athens became overwhelmed.

Schools, universities and public services were the first to shut down, followed later by cafes, but nothing could stop the virus on its path of destruction as it demonstrated an insatiable appetite for life. Theodoropoulou’s grandmother had no way to communicate with her husband and didn’t even know he’d gotten sick before being informed that he had died – aged just 41. She wanted to retrieve his body but was forbidden from approaching the area and was told that he’d be buried at a cemetery there.

As the pandemic made its way through Greece, 27-year-old journalist Konstantinos Faltaits studied events on his native island and published his findings the following year in a book where he vividly describes a “disease that befell the earth like an evil curse,” hitting Skyros “with a ferocity akin only to the plagues of the Middle Ages.”

Anastasia Faltaits, the writer’s granddaughter and vice president of the museum on Skyros named after him, went back to the book a few weeks ago. “I read it from a different perspective today and I admit that I lost sleep over it. It gave me a knot in my stomach because of the situation today. There are incredible similarities, not just in terms of the disease, but also in people’s behavior. Then, just like now, there were people who helped, others who lost control and others still who took advantage of the difficult situation,” she says.

According to her grandfather, the virus reached Skyros in the early fall. No one knows how, though it was likely brought by someone returning from Athens. Most of the houses at the time were crammed around the island’s castle and even though people stayed indoors, the virus spread with incredible rapidity through the population. Faltaits’ book includes facsimiles of telegrams from local authorities to Athens, desperately asking for medicines and supplies to deal with the outbreak, though the state’s response appears to have been limited to a recommendation for setting up a sanitation committee and a small shipment of baking soda and a few injections that disappeared within a day.

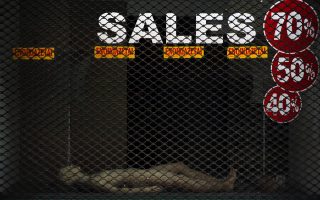

The outbreak tested personal relationships and stretched the island’s social fabric. “You read of people who tried to help the dying. Brave doctors (who also became sick) and regular people who offered to help by delivering a plate of food to their neighbor or later, when burials became a serious issue, dug graves and carried bodies. There were also tradesmen who profiteered on basic supplies or sold shrouds at exorbitant prices,” says Anastasia Faltaits. Skyros had a population of 3,200 at the time; two-thirds did not make it through the pandemic.

“The scenes described in the book are terrifying, especially when you consider that we nearly experienced a similarly difficult situation today,” she says. But there was light at the end of that tunnel too, as treatments improved, and by December 1918 the plague had run its course. Despite the enormous losses and economic hardships, the survivors were gradually able to return to some semblance of normalcy.

Over in Athens, the newly widowed Theodoropoulou moved in with her brother and slowly got back on her feet. She was able to get Tzortzis’ body exhumed three years later and took his remans to Anafi for burial. “She loved him so much; she dreamed of him every night until she died,” says the couple’s 75-year-old granddaughter, thinking of her grandfather and how history is repeating itself 102 years later.