The West faces the new Eastern Question

“From time immemorial Europe has been confronted with an ‘Eastern Question.’ In its essence the problem is unchanging. It has arisen from the clash in the lands of South-Eastern Europe between the habits, ideas and preconceptions of the West and those of the East. But although one in essence, the problem has assumed different aspects at different periods.”

This is how Sir John A.R. Marriott describes the Eastern Question in his classic text “The Eastern Question, An Historical Study in European Diplomacy.” This definition of the Eastern Question, though framed a century ago, has proved an enduring tool for understanding developments in our region.

Until the early years of the 20th century, the long-drawn-out process of the shrinking of the Ottoman Empire and its geopolitical sway was central to the Eastern Question. The fall of the empire and the establishment of the modern Turkish state in 1923 were sealed with the territorial and other terms of the Treaty of Lausanne, closing a major chapter in the Eastern Question.

Implementing the Kemalist vision, modern Turkey tied itself to Europe and the West, primarily strategically, but also politically and culturally. A key member of NATO and candidate for membership in the European Union, for many decades Turkey stopped being part of the broader Eastern Question as defined by Marriott.

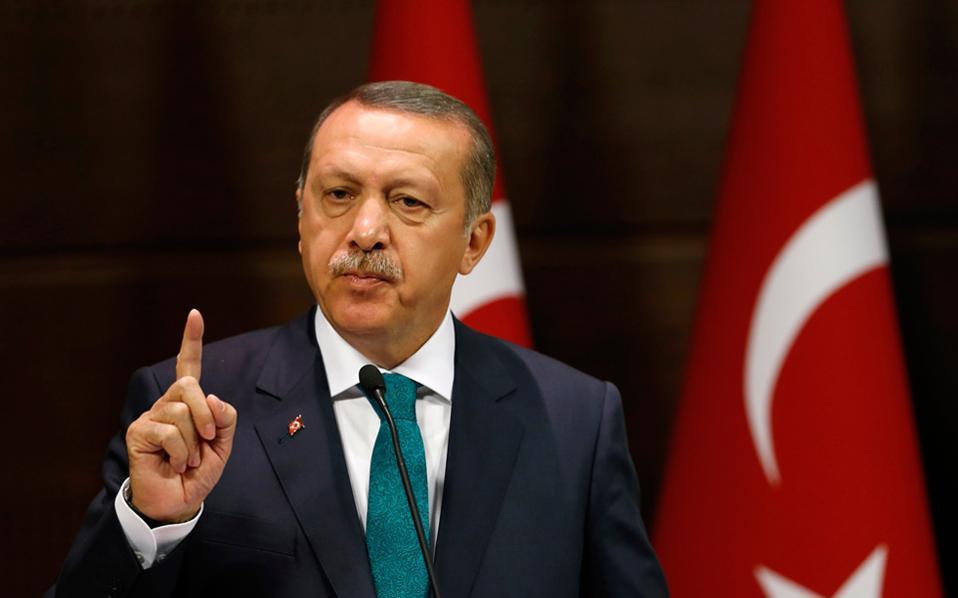

However, over the course of 15 years of ideological and political regression, Turkey, under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has revised its previous strategic choices and directions.

It is moving deeper and deeper into the world of Islam. It is systematically disputing the terms of the Treaty of Lausanne, trying to overturn it and ignoring the fact that it is the bedrock of stability and peace in the wider Eastern Mediterranean region. Ankara has adopted a “neo-Ottoman” strategy, projecting its power, presence and influence in former Ottoman territories from Syria to Libya and from Cyprus to the Caucasus, a region that includes the Aegean.

Thus, Erdogan’s Turkey, under the authority of a single man, is steadily diverging from the West. In an about-face from the orientation it adopted in the early 20th century, Turkey is the centerpiece of the new Eastern Question. In place of Ottoman contraction, we are witnessing neo-Ottoman expansionism. Turkey is shifting from historical ebb to a strategy of expansionist high tide. Viewed in this context, the attempted mass breach of Greece’s Evros border from Turkey by migrants last March is anything but an isolated incident. It was a clear, albeit indirect, clash between East and West on the Greek and European border. This dangerous play was averted by a firm Greek response supported by Europe. But this must not lead us to underestimate the importance of that attempt to weaponize the migration crisis.

The “Blue Homeland” policy that Turkey, in defiance of international law, is persistently invoking against Greece, Cyprus and other Eastern Mediterranean countries – including Israel and Egypt – is the practical expression of Turkey’s revisionist strategy. A strategy that, apart from anything else, is blocking important European energy developments. The procurement of the powerful non-NATO S-400 missile system is another expression of Turkey’s aspiration for strategic autonomy.

Europe and the US now find themselves having to manage the “Turkish problem” as a new and serious dimension of the Eastern Question in the 21st century.

Paragraph 35 of the recent conclusions of the European Council could not be clearer: “The EU will seek to coordinate on matters relating to Turkey and the situation in the Eastern Mediterranean with the United States.” With this prospect in mind, the European Council gave High Representative Josep Borrell two mandates: (a) to prepare a report and policy proposals on Turkey and (b) to take forward the proposal of a multilateral conference on the Eastern Mediterranean.

The EU’s political condemnation of Turkey’s conduct coincided with Washington’s decision to impose sanctions on its NATO ally, suspending delivery of defense equipment and know-how due to Turkey’s failure to abide by key strategic choices of the Alliance. These sanctions – imposed for good reason – sparked strong reactions in Turkey and further exacerbated tensions in the Alliance resulting from the two incidents involving the Turkish Navy and the French and German naval forces in the context of Operation Irini, which is enforcing the arms embargo on Libya. But Turkey has also long created tensions through its conduct toward another NATO ally, threatening Greece with war if it should exercise its rights under international law.

The serious rifts Turkey is causing in the cohesion of the North Atlantic Alliance are more than obvious. Where do we go from here? What policy should the US, Europe and Greece – as a directly threatened ally – adopt against Turkey?

Due to its major economic interests in Turkey, the EU is in an awkward policy position: It is trying to rein in Turkey’s geopolitical aspirations without pushing it away from the West. The US has also adopted a carrot-and-stick approach.

In my recent address during the parliamentary debate on the budget, I raised these concerns and argued that the West – the European Union and the US – will first have to halt Turkey’s dangerously destabilizing policy and only then move forward to a positive agenda for cooperation, with strong conditionality and strict prerequisites and conditions.

In other words, the West’s policy on Turkey must be based on the triptych of “containment, dialogue, partnership.”

This is the blueprint of Greek foreign policy, as implemented by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. A multidimensional policy that combines diplomatic and military deterrence with three main goals: (a) responding to and limiting our neighbor’s unlawful and aggressive actions, (b) preparation, based on international law and treaties, of a clearly delineated dialogue launched through the exploratory talksm and (c) working to restore beneficial bilateral cooperation with respect for good-neighborly relations.

Of course, this requires a lasting detente. Not just a short break followed by a return to tensions. Not blackmail, threats or violation of rights.

The Turkish leadership has to realize that the emergence of a new kind of Eastern Question and conflict with the West will not work in its favor, regardless of any temporary boost the authors of the revisionist strategy might see in their domestic popularity.

Giorgos Koumoutsakos is Greece’s former alternate minister for immigration and asylum policy.