Alekos Fassianos (1935-2022): The voice of past and present

I was relatively new at Kathimerini when I interviewed Alekos Fassianos for the first time, at his home, in the late 1990s. The entrance was like some magical gateway into a universe designed entirely by him, from the door handles to the lighting fixtures on the walls. I sat down on the sofa in a state of wonder and observed every small detail. Kind and intuitive, he sensed my awkwardness and became more talkative, something he was not accustomed to. He also paused between sentences, as if speaking was hard for him. This was certainly not the case when it came to drawing. An inveterate doodler who drew on napkins, menus and paper tablecloths at tavernas, his hand moved like mad as, in single strokes, it formed cyclists, swimmers, boats and houses. It was as if the pencil or the paintbrush were an extension of his hand that was driven by an almost supernatural force which gave each line shape and substance.

He told me his entire life story in that first interview, starting with his grandfather who was a priest at a church right beside the house where he was born in Agioi Apostoloi, northeast of Athens. He associated his early childhood with the smell on incense and the darkness of old Byzantine churches illuminated only by candlelight. The saints with their halos and military dress were the heroes of his fairytales, armed with lances, slaying beasts. In central Athens when he was older, he would wander the streets around Vathis Square and watch the people in this poor neighborhood struggling to eke out a living. But he also visited the Acropolis and all the other museums in Athens on outings with his mother, a philologist with a passion for ancient history.

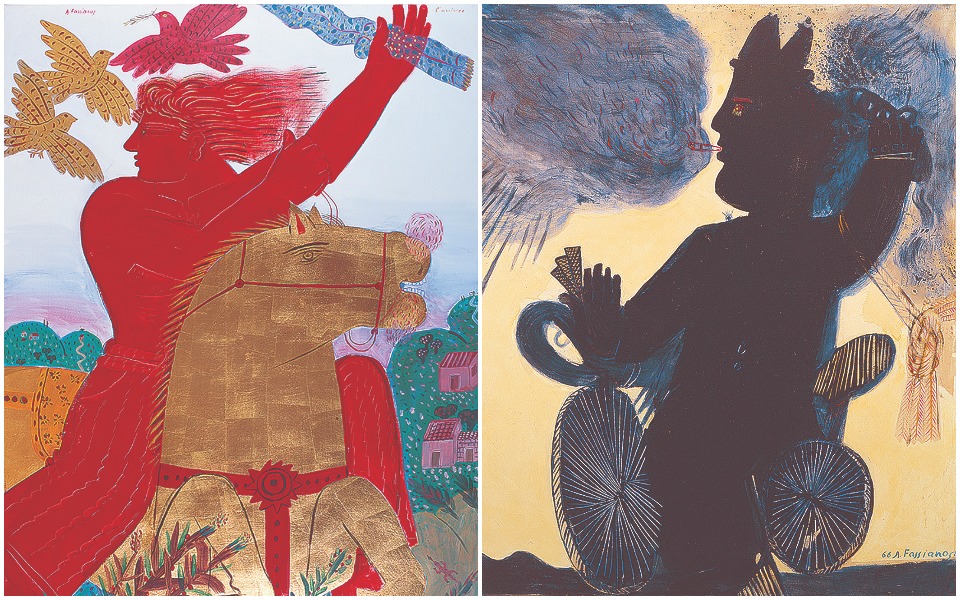

All the figures on the icon screens, the ancient vases and the city streets melded – he used to say – into one in his mind. “I was unconsciously creating my future art in this setting. Without such scenes and symbols, where would I be?” he stressed.

His father was a musician and he learned to play the violin from a young age, which is what took him to the Athens Conservatory, where he met composers Yannis Markopoulos and Mikis Theodorakis. But art was his true calling, so he passed the exams to get into the Athens School of Fine Arts in 1955, where he was taught by such greats as Yiannis Moralis and Yannis Tsarouchis. He also hung out at the legendary Cafe Brazilian, spending countless hours in conversation with Odysseas Elytis, Takis Sinopoulos, Eleni Vakalo, Miltos Sachtouris, Andreas Embeirikos, Costas Tachtsis and other influential figures of the arts and letters. He developed a profound interest in literature and poetry during those years and went on to illustrate numerous publications for them.

“These people were such a treasure trove to me that I wanted to express my gratitude and admiration in some way,” he said. It was the same with stage design, which earned him a special place in the Greek theater.

A scholarship in 1960 changed his life by sending him to Paris, where he studied lithography. Just as growing up he had been surrounded by streets named after great Frenchmen like Victor Hugo, Charles Nicolas Fabvier and Francois-Rene de Chateaubriand, in Paris he soon joined the circles of great intellectuals of that time, like writers Jacques Lacarriere and Yves Navarre. He also met Greek artists Vassilis Sperantzas and Nikos Stefanou, with whom he went on to create the famous studio in the Athens district of Kallithea. It was in a house with palm trees that the three rented when they returned to Greece from France in 1963 and lived up until the start of the dictatorship in 1967. The three friends became known for their parties and sense of fun and the house was a place of debate, discussion and synergies. It was also where his signature “little men,” symbols of the Greek middle class, were born.

“I did the first smoking cyclist there,” he reminisced during our first interview. “I was standing at the window looking at the sky when it came suddenly, inspiration, like the light of the Holy Spirit, to paint a man riding a bicycle with a cigarette in his mouth and smoke and hair billowing out. The room seemed to fill with clouds as I painted it.”

Fassianos returned to Paris when the military regime took over in Greece and that was when his career really took off, with shows at the gallery of Alexander Iolas, among others. French critics and art aficionados regard Fassianos as the artist who created the enduring connection between the gods of Olympus and mythology, to the Byzantine saints and on to the modern Greeks living under a totalitarian regime. He may also have been the last Greek to create such a marriage, thanks to his education and experiences.

Fassianos returned to Paris when the military regime took over in Greece and that was when his career really took off, with shows at the gallery of Alexander Iolas, among others. French critics and art aficionados regard Fassianos as the artist who created the enduring connection between the gods of Olympus and mythology, to the Byzantine saints and on to the modern Greeks living under a totalitarian regime. He may also have been the last Greek to create such a marriage, thanks to his education and experiences.

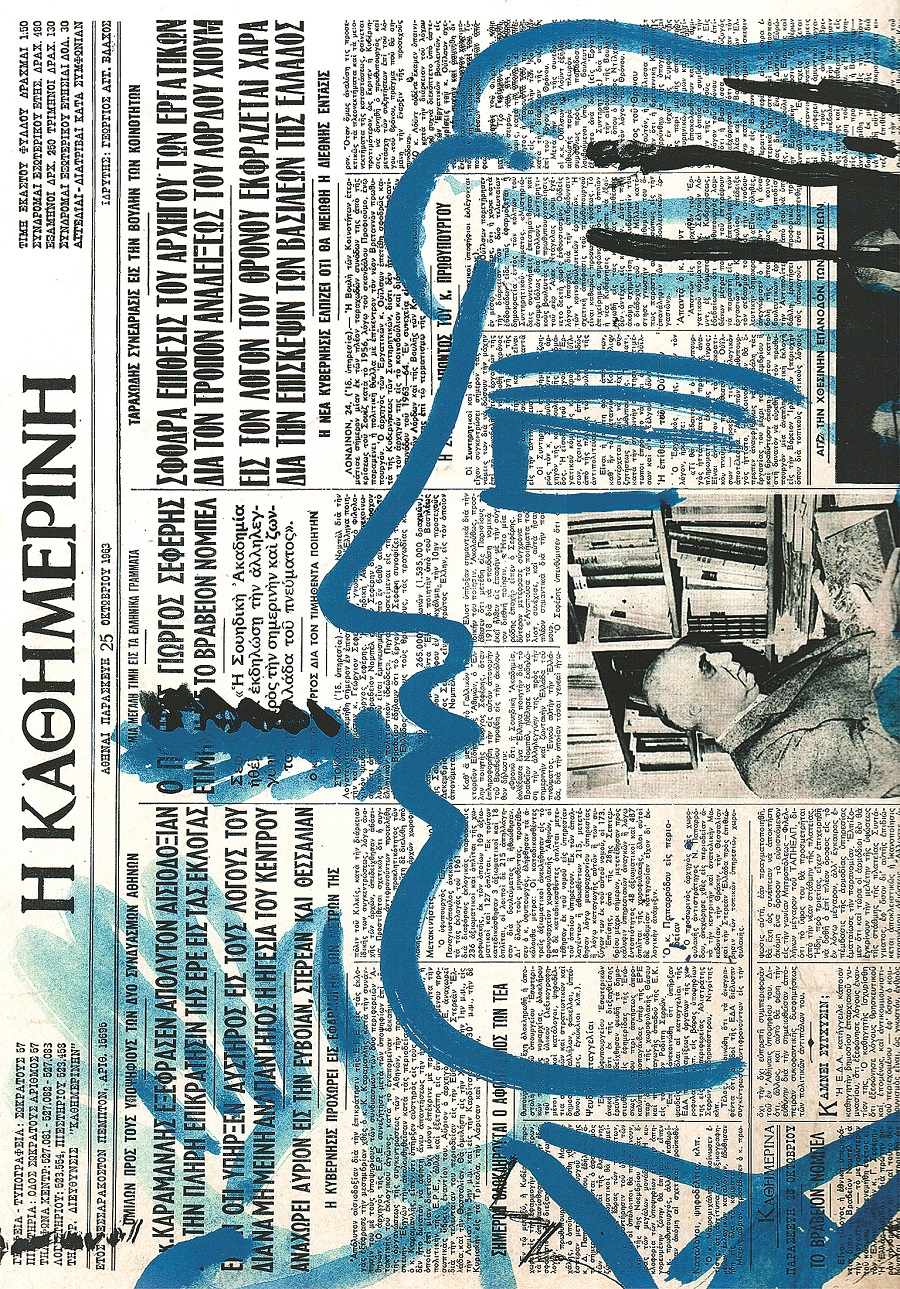

The last time I saw Alekos Fassianos was in 2019, when he gifted Kathimerini a painting from a charity auction held as part of the newspaper’s celebrations of its 100-year anniversary.

“Wait,” he said, as I was preparing to leave. And he gave me a small painting with a bright-red figure that now looks at me affectionately from across my desk.