Don DeLillo on this crazy, puzzling world we live in

“It was Don DeLillo whiskey neat / and a blinking midnight clock.” This is the opening of the song “Gold Mine Gutted” by American alt-rockers Bright Eyes, and if singer-songwriter Conor Oberst was looking to describe the image of sophisticated solitude steeped in alcohol before going on to lament the gutted youthful innocence of his generation, he also achieved something else at the same time: to paint in poignant yet sparse terms the heroic loneliness felt by Don DeLillo readers, as they connect with heroes who are just like themselves, tossed and isolated in a world flooded by signifiers that are devoid of meaning and sending contradictory signals.

Reading DeLillo’s books is a mystical experience that brings flashes of insight. At the end though, the reader feels a part of a big community, not just of readers but of communicants in the secrets of a puzzling era. His work is not a psychological narrative of personal tragedies or family meltdowns, but embodies every individual particularity and every human experience in the panorama of life in the postwar era. History and politics, science and technology emerge as pillars of the entropic systems programmed by tech gurus and run by unreal magnates and political groups to torpedo madmen and terrorists.

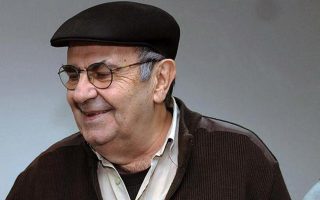

The multi-award-winning American writer and last year’s recipient of the National Book Awards Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, one of the few writers to be considered a living contemporary classic, spoke to Kathimerini just a few days before a scheduled visit to Greece to speak at the Onassis Cultural Center on March 16.

DeLillo is an intellectual writer who, through a plethora of ideas and subjects, has tuned into the impact of sundry conspiracy theories, one of the most resilient forms of social schizophrenia. So does he share the view of E.L. Doctorow, that “writing is a socially acceptable form of schizophrenia,” as he stated in a 1986 interview with Paris Review?

“I don’t think of writing as paranoid at all,” he says. “My work has at times addressed certain elements hovering in the culture of the 1960s and beyond. We became a paranoid society in the years following the assassination of President Kennedy and this tendency became instilled for a time by the violence and unrest that followed. Some of my fiction made note of this, but it wasn’t my paranoia; it belonged to the culture.”

Image

One of the recurring motifs in his work is the concept of image. Image can relate to the “the most photographed barn in America” in “White Noise” or to the reclusive writer Bill Gray in “Mao II” who agrees to be photographed for the first time in his career at an advanced age. For previous generations, a photograph was a proclamation of resistance against death. This association, however, has receded, if not disappeared almost entirely today thanks to the vast number of photographs produced on smartphones and recycled on social media.

“Maybe our visual sense is being reduced to the size of a cell phone image,” comments DeLillo. “A predominant experience today occurs when we see people making an image of themselves as they extend an arm and aim a cell phone.”

DeLillo portrayed the era of global terror toward the asymmetric threat of terrorism before its advent, particularly in “Mao II” and less so in “Players.” What is his reaction to the recent wave of terror?

“My thoughts concerning terrorist attacks are the same as other people’s. Immediate and deep,” he says. “When I attempt to write about such matters, I try to find a sense of the lives and minds of the characters involved. This is fiction that does not want to shrink in the presence of an important contemporary challenge.”

DeLillo will be publishing his 17th novel in May and, as he turns 80 in November, “Zero K” may be as seminal as his 1997 “Underworld,” considered the crowning moment of most of the ideas he had explored until then.

“I have no clear sense of a career reaching for an epitome in the novel ‘Zero K.’ The idea for the novel developed as a writer’s response to a visual image, which has occurred in my experience through the decades. Then, day by day, the characters and landscape take shape on the white sheet of paper in my typewriter,” says DeLillo.

The visual images shaped by sentences and paragraphs on a page have such an effect on him that at one point in his career he started writing one paragraph on each page in order to maintain as much control as possible over his sentences. How does a writer who is so obsessed with language feel when he can’t fully control it?

“I don’t feel betrayed by language; what I may feel at times is that I have to think more deeply into the possibilities inherent in an idea, or a scene, or a particular character’s experience from one minute, one gesture, to the next,” he answers.

Greece experience

DeLillo’s experience in Greece is one of the few parts of his personal life that he has delved into in interviews, confessing the benefits he gained as a self-exiled writer from 1979 to 1982, when he lived in Athens and used his house in the Kolonaki neighborhood as a base from which to also travel to India and other countries further east.

“My stay in Greece turned out to be crucial to my writing,” he says. “The language, the people, the history, the walls and monuments with their inscribed letters and words – all of this gave me a sense of the deeper involvement I needed to find in shaping a sentence, and of the visual component, the ‘architectural’ element that is present in letters and words. In a sense what I was doing was rediscovering the alphabet.”

His time in Greece, however, was not his only enriching European experience, as his acquaintance with great writers from the continent shaped his literary education in the early years of his career.

“I read a fair amount of European fiction when I was beginning to think of myself as a writer. I have no sense of direct influence in this matter – simply the deep appreciation that I experienced in reading work of such depth and range. Here was Faulkner, there was Camus. And those were probably my most rewarding years as a reader,” he says.

Today, it is DeLillo who is influencing successive generations of readers and writers with his significant legacy, another chapter in the identity of modern American literature, as it has been shaped by Philip Roth, Cormac McCarthy, Toni Morrison and Thomas Pynchon.

“I believe that certain writers, in their best work, have helped shape the environment in which we live and think. They open daily life, ordinary hours and minutes, to a range of insights that the reader might not otherwise experience,” says DeLillo. “The various Americas – Roth, McCarthy and others – are all set under a contemporary landscape that waits for younger writers to extend the vision, stretch the language.”

Don DeLillo will be speaking at the Onassis Cultural Center (107-109 Syngrou, tel 210.900.5800, www.sgt.gr) on Wednesday, March 16, starting at 7 p.m. Admission is free on a first-come, first-served basis, starting an hour before the event.