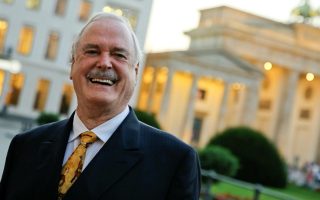

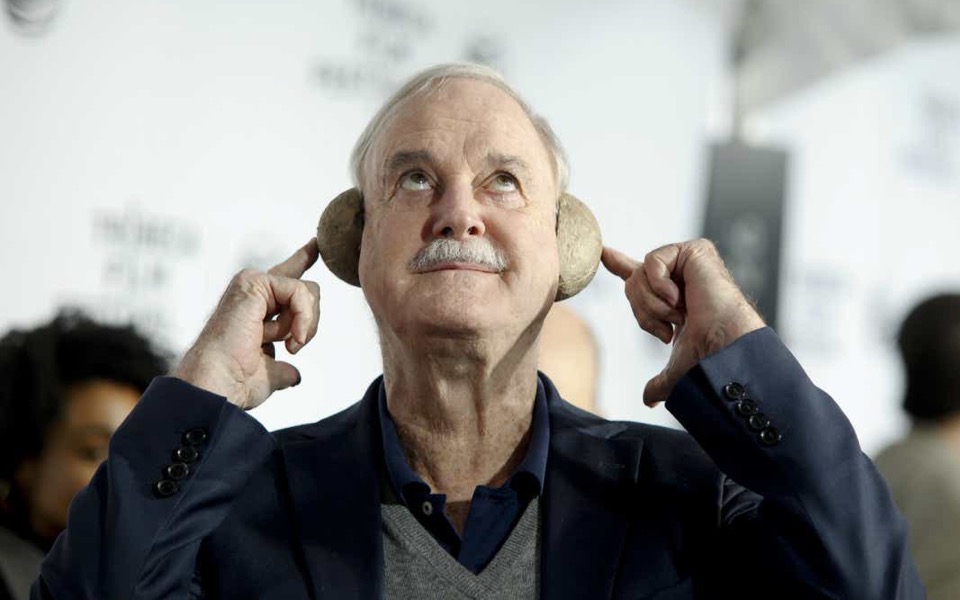

For Monty Python star John Cleese, ‘life is a comedy’

“Some people think life is a tragedy and we are all going to die, and some people think life is a comedy. I belong to the second group,” John Cleese tells me from the other end of the telephone line.

For the British comedy actor and co-founder of the legendary Monty Python comedy group, death and what he sees as its humorous side are an endless source of material. Thinking back on the “Dead Parrot” sketch from Monty Python’s legendary “Flying Circus” series, first aired in 1969, or the memorable (and shockingly hilarious) eulogy he delivered for his friend and comedy partner Graham Chapman in 1989, the 79-year-old Cleese seems comfortable with the subject.

“I always had a catholic sense of humor. I don’t mean Roman Catholic, I mean wide parameters. I sometimes enjoyed quite subtle humor and sometimes slapstick. I enjoy those and everything in between but in later years I think I’ve become more amused by what I call black humor, which is often humor about things that make people uncomfortable, like death,” he says.

And what is comedy to the man who created the Ministry of Silly Walks? According to French philosopher Henri Bergson, he says, laughter is a social sanction against automatic behavior, which means that “when people fall into automatic behavior rather than proper behavior they become fundamentally ridiculous and we laugh at them.” The British, says Cleese, “have a strong sense of irony, which in many ways is a delight. But it has also to do with the fact that they are uncomfortable with emotion and they would rather deal with it in an indirect way rather than a direct way and irony is the way they choose.”

On the thorny issue of political correctness, Cleese argues that it “can be a source of humor because it’s a good basic idea taken too far by people who have no sense of humor themselves and do not understand the philosophical nature of humor.”

And what is the philosophical nature of humor? “That all humor is critical but it’s only cruel if it is offered in a cruel way. The vast majority of humor is among our friends and families. It’s fun, gentle and teasing, which if you look at it carefully is a bit critical but never unkind. In fact that kind of affection and teasing often bonds people together.”

But what about the risk of offending people?

“You simply have to understand – and people seem to forget this – that people have different senses of humor. With politically correct people it is a bit like everyone is having a good time and then the maiden aunt or the maiden uncle comes downstairs and everyone stops moving around and laughing a lot and behaves very gently, very correctly, until the maiden aunt or uncle decides to go upstairs again and everyone continues to have fun. The question is: Are we going to take as arbiters the people who are most sensitive, the most easily upset?”

Increased sensitivity, which Cleese says tends to be more prevalent among younger audiences, is one of the reasons why Monty Python may not have the same resonance today as it once had, even though the group’s videos continue to enjoy immense popularity on YouTube, the comedian says.

“I’m aware that a lot of the younger generation is, I think, contaminated by some of the more extreme political correctness ideas and probably would find things that would offend them. But they will find things to offend them anywhere,” he adds. “It is like they think humor hurts people. What I like about some of the best people is that they can laugh at themselves. They would hardly laugh at themselves if that hurt them.”

A Cambridge law graduate, Cleese made his career debut with “The Frost Report” at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, going on to work as a writer and actor on numerous productions in Britain and the United States, which is where he met fellow Python Terry Gilliam and his first wife, actress and co-writer of the successful “Fawlty Towers” television series, Connie Booth.

He was fortunate, he says, to have “escaped” from a life as a lawyer. “I have decided in the last 10 years that comedians are more valuable than I ever thought they were before because they bring a certain balance to a world that is going very, very bad,” he says.

He later teamed up with Chapman, Gilliam and the rest of the Monty Python crew (Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Michael Palin) to launch the “Flying Circus” series, going on to “Fawlty Towers” fame in the mid-1970s and exploding onto the international big screen in 1989 with the screenplay for and a starring role in the hit romcom “A Fish Called Wanda.” Together with Chapman, Cleese is credited with writing some of Monty Python’s most memorable work and in contrast to what most people believe, it was an exhausting process.

“We worked very, very slowly, and I always have. Graham and I would write 3.5 minutes of good dialogue every day. Some days we would have an off day and the next we would write 7 minutes. That is not a lot. But if you manage that for five days a week, you get about 20 minutes, and with other writers that’s more than enough material for a show.”

Turning to the influences that shaped the work of Monty Python, we talk about 19th century nonsense literature and writers such as Lewis Carroll. Cleese adds the poetry of Edward Lear and the novels of Robert Louis Stevenson and Jerome K. Jerome’s “Three Men in a Boat,” which his father, Reg Cleese, said was the “funniest book ever written.” “There’s always been a strip of comedy and absurd writing, even during the times of British history when we were most grim and humorless, like the Victorian era,” he says.

Cleese has spent the past few years touring the world with his solo show, “Last Time to See Me Before I Die,” which he will be bringing to Athens’ Herod Atticus Theater on September 20 as part of events celebrating the British Council’s 80th anniversary in Greece.

Does he have any experience of Greek humor? “I’m afraid I haven’t. I think your 2,000-year-old comedies were fascinating, but it is hard to see how much people actually laughed at it,” he says.

“The only thing I would like to note is that there are many people in my family who have been very distinguished in your country’s history. There was Sophocles, Pericles and this Cleese: I’m the latest of a long line of distinguished Greek comedians,” he quips.

Our conversation inevitably turns to Brexit, as Cleese has publicly supported Britain’s departure from the European Union. “I’m not quite as concerned as anyone else,” he says. “I think it would be absolute chaos for a time but I don’t think deep down that it will hurt many people and after that we will find a way to do business with each other. It seems to me that we like the Europeans and Europeans quite like us but what is infuriating is not our relationship to the Europeans but our relationship to a particular political framework that’s been worked out. We will work out another one and in a few months’ time people will wonder why we were in a panic.”

On Greece’s own close call with Grexit, Cleese argues that the country “was treated really badly for the interests of the German bankers, so I’m not a big fan of the EU.”

We also discuss the comedian’s controversial tweet a few months ago in which he said that London was “not really an English city anymore.” He stands by that claim. “It’s true; it has become so cosmopolitan that it has no English feeling about it,” he says, adding this is not his view, but that of friends visiting from abroad.

“But if you say that then you are perceived to be a racist. Which is complete nonsense. I’m all for people coming to England bringing their cultures with them, but I would also like to combine that with an interest in the parent culture, the culture of the country they come to live in,” he says. “If I came to live in Greece I would make a point to learn about Greece’s history, I would learn to speak Greek as well as I could and I would be interested in the Greek culture and political scene. I’m all for cosmopolitanism, but I think the parent culture does not need to be neglected to the point where we can’t really see it any more.”

Tickets for John Cleese’s show at the Herod Atticus Theater on September 20 can be purchased online at www.viva.gr or by phone at 11876. The show starts at 9 p.m.