John Travlos, anatomist of ancient Greece

A man of action rather than words, of simple ways and profound intellectual powers, John Travlos (1908-1985) was an archaeologist’s architect, with the ability to envision the whole from a fragment. Thanks to his painstaking work, he is also responsible for an impressive number of buildings and monuments in Attica and beyond that we tend to take for granted.

“He had the gift of complex thinking,” says Angeliki Kokkou, an archaeologist who worked with Travlos for 20 years and author of a richly illustrated book on his life and work, published recently by Kapon (in Greek).

Travlos’ contribution was significant both in volume and importance, and it unfolds in Kokkou’s biographical narrative. Perhaps his most famous project was on the restoration of the Stoa of Attalos at the Ancient Agora in the 1950s and his work at the Archaeological Site of Eleusis. Over the course of a lengthy and full career, however, Travlos worked on a plethora of excavations and archaeological studies for monuments that embody the enduring qualities of Hellenism.

“John Travlos: His Life and Work” begins with Kokkou’s personal assessment of his contribution and personality, and evolves into a retrospective of his career, covering its biggest milestones and also offering a glimpse into the mind of a brilliant scientist. Balanced and well researched, the book is largely based on Travlos’ archive, which was donated by his family to the Archaeological Society at Athens.

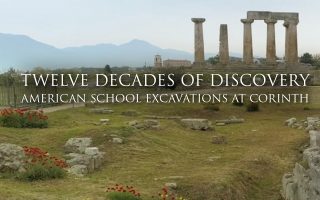

“He kept detailed records of all of his projects,” says Kokkou, noting that a large number of Travlos’ drawings and studies are held by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), with which he worked closely on the excavations at the Ancient Agora. Travlos had also entrusted Kokkou with a part of his private archive.

The Athens Polytechnic architect was as knowledgeable about and interested in Byzantine and modern monuments as he was in ancient ones. Kokkou worked with him on the monumental edition “Ermoupolis,” published in 1980, while shortly before the dictatorship, in 1967, he had published the now-classic photo book “Neoclassical Architecture in Greece,” with Commercial Bank of Greece. His study on the urban evolution of Athens from prehistoric times to the early 19th century (Kapon, 1960 and 1993), meanwhile, is still regarded as a seminal piece of work.

“It takes a lot of happy coincides in a person’s life and a certain intellectual and spiritual endowment for them to do what they are destined for,” writes Vasileios Petrakos in the new book’s prologue. Travlos, he adds, “seemed favored by the fates.”

It is now 35 years since he died, yet Travlos remains largely unknown to the general public. This is partly because of his character – “he was low-key,” says Kokkou – but also because of his complete immersion in his work.

At the Ancient Agora excavations with the ASCSA, Travlos played a pivotal role in the final result of the Stoa of Attalos’ restoration, a momentous task that had started in 1949. His ability to locate the exact position of ancient structures and to visualize them as part of a whole was a talent he had cultivated through extensive research and study.

His involvement with Eleusis, regarded as one of the toughest of Greece’s archaeological sites, started at a young age when one of his professors, Anastasios Orlandos, introduced him to the head of the Greek Archaeological Service, Konstantinos Kourouniotis. Travlos worked with the archaeologist on the Sacred House in 1937, but the onset of the war brought the project to a halt and the young architect went off to join the Second Regiment of Bridge-Builders. We have some marvelous drawings from that time which he sent his family in his letters.

An avid sketcher, he also left wonderful drawings of neoclassical Athenian houses that he did in 1929, at the age of 21.

He returned to Eleusis after the war and in 1950 published another seminal study on the sanctuary.

Travlos was born in Rostov, southern Russia, in 1908. His father was in commerce and in 1912 his mother took her five children (he had four sisters) and settled in Athens, on Dafnomili Street in the downtown district of Exarchia. He had a middle-class upbringing and graduated from the Varvakeios School before attending the Athens Polytechnic. Apart from Orlandos, one of the country’s foremost authorities on Byzantine architecture, he was also taught by the renowned architect Dimitris Pikionis.

He enjoyed walking in nature and around the city, drawing and exploring, and was able to strike out further after acquiring his first motorcycle in 1933. That was the same year that he met his wife, Alexandra, with whom he went on to have two daughters. He continued to live in central Athens, in a building on the corner of Alexandras Avenue and Loukareos Street, where he lived from 1960 until his death in 1985.

As a young man, Travlos also sketched Attica’s Byzantine churches, only to go on to restore one of the capital’s most important such monuments, the Church of the Holy Apostles in the Ancient Agora.

His passion for neoclassical architecture, moreover, led to the challenge of renovating the Dekozi-Vouros Mansion so that it could be turned into the Museum of the City of Athens (by Lambros Eutaxias), where we have the only model of Athens from 1842, also the work of Travlos. He also did the Mela Mansion on Sofokleous Street for the National Bank of Greece, among a plethora of other projects that testify to the brilliant mind and talents of this important architect.