Electoral rule reform: The change we (don’t) need

Recently the debate about changing the electoral system was revived following a proposal by small centrist opposition party To Potami to adopt the German electoral system. This is a mixed-member proportional system where voters select their representative MP in a single-member district ballot and their preferred party list in a second national-district ballot. According to the proposed rule, the distribution of seats in parliament would be much more proportional compared to the current rule – a disproportional system that assigns a majority premium (a 50-seat bonus) to the plurality winner of the election.

This isn't the first time the electoral rule has come up for discussion. Ever since Greece's traditionally stable two-party system collapsed – resulting in record levels of electoral fragmentation in the May 2012 elections – many other small parties (including the once-dominant PASOK) have expressed the need for a more proportional electoral system.

As is always the case in any major institutional reform – especially electoral reform – the trade-offs that introducing any significant changes may entail need to be carefully examined. It is now widely accepted among scholars who study electoral rule reform that the key trade-off which policymakers are faced with is that between representativeness and accountability. While proportional rules result in a more accurate reflection of citizens' preferences in parliament, they also make the prospect of coalition governments more likely. On the other hand, more majoritarian rules tend to generate stable single-party governments, which are less representative but, in principle, more accountable; people know which policy mix they have selected and whom to hold accountable if that policy package is not delivered.

However, the above is not the only trade-off that we need to worry about. As we found in our recent study,1 electoral rules can have important effects on the degree of party-system polarization: More proportional electoral systems generate strong centrifugal incentives for parties to adopt more extreme policy positions, while more majoritarian electoral systems (such as the one currently in place in Greece) generate strong incentives for parties to moderate their political platforms and converge to the center. This follows from the fact that majoritarian systems generate strong incentives for each party to capture the center and win the election outright, which, in turn, translates into a disproportional amount of parliamentary power. That is, less proportional systems – unlike what popular wisdom would have us believe – tend to induce more moderation and result in a less polarized party system. Therefore, introducing a more proportional electoral system (such as the German one) might not be a good idea after all: Further polarizing an already highly polarized and fragmented party system might put the final nail in the coffin of party-system stability, which Greece has been seriously lacking over the past few years.

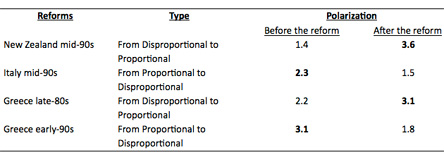

Empirical evidence that we have gathered confirms the above point as it suggests that major electoral reforms (that is, changing very disproportional electoral systems to very proportional ones and vice versa) are strongly associated with significant changes in parties’ positions and the overall level of party-system polarization. Despite the fact that such reforms are not very frequent, all existing examples seem to corroborate the presented view. A systematic empirical analysis of a series of electoral reforms in a sample of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member-states suggests that the above pattern is extremely solid: Majoritarian reforms are linked with less polarization, while the opposite is true for more proportional ones. For example, the electoral rule reforms in New Zealand and Italy brought about a steep and significant change in those countries’ polarization levels. Perhaps more importantly, in Greece, the electoral reforms of both the late 1980s (from a disproportional rule to a very proportional one) and the early 1990s (from a very proportional rule to a very disproportional one) went hand-in-hand with significant alterations in party-system polarization. It is noteworthy that polarization levels in all these cases shifted in the expected direction (see Table 1).

Table 1. Electoral reforms and party-system polarization levels (measured by the distance between the most distant platforms on a 0 (left) to 10 (right) scale, using data from the Manifesto Project Data Set version 2012.

Of course the electoral rule is not the only determinant of party-system polarization (the number of parties, economic conditions, and other factors also play a crucial role). But since the electoral rule clearly affects parties’ payoffs and thereby their incentives to moderate or move toward the extremes, one should seriously take all these considerations into account when designing an electoral reform. This is particularly the case with Greece and the proposed electoral rule reform. The undeniable need to adjust the winner’s bonus to a more reasonable level (as the 50-seat bonus reflected the balance of power under the old two-party system) should not lead us to adopt a system that would further destabilize an already polarized and highly fragmented political system. Thus, in light of the recent debate in Greece on electoral reform, our research suggests that a more proportional electoral system would most likely further increase party-system polarization and, in addition, could have a series of negative implications for voters' welfare and the stability of the party system.

First, under a more proportional electoral system the aggregate level of party-system polarization would increase further. In fact, most Greek voters are still relatively moderate – despite six years of austerity – and strongly support the country’s participation in EMU. Therefore, in his quest for the support of those centrist voters who can grant any party the electoral victory (and, of course, the 50-seat electoral bonus) Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has gradually moved SYRIZA toward more moderate pro-EU positions; a simple comparison between SYRIZA’s 2015 manifesto and its manifesto back in 2012 is quite telling in that regard. It is hard to see why SYRIZA would have adopted such a pro-EU position in the absence of the centripetal incentives that the current electoral rule provides. If a marginal increase in centrist votes can only translate into a couple more extra seats, why risk splitting the party by adopting a more moderate pro-EU platform and thereby marginalizing the more radical anti-EU elements of SYRIZA?

Second, under a more proportional system voters' welfare would further decrease as a result of limited accountability. Proportional systems result in coalitions between parties that have strong incentives to propose very distant (polarized) platforms during the pre-electoral campaign period. As a result, the final policy outcome, which directly affects voter welfare, is a combination of very distinct (and polarized) platforms that no voter has actually voted for. In turn, this further delegitimizes the political process by disassociating the end policy outcomes from voters’ actual choices at the ballot box. As a result, any attempt to increase citizens’ representation by making the electoral system more proportional might have additional unintended consequences: Not only would we sacrifice democratic accountability and policy moderation but, at the same time, we might even undermine the legitimacy of the political process.

Finally, a more proportional electoral system would further exacerbate the current fragmentation of the party system. Despite all the critique – warranted or not – leveled against Greece’s old two-party system and its former traditional parties of government (PASOK and New Democracy), it is no exaggeration to argue that Greece experienced one of the most politically stable and economically prosperous periods in recent history partly thanks to its stable two-party system.

Therefore, despite all the good intentions, it might not be such a good idea to introduce the German mixed-member proportional electoral system after all. One might say that we have had enough German-inspired “reform” already.

But then, what are the elements that a new electoral system should have?

Firstly, it is still the case that the new system has to be less favorable toward the winner at the expense of the runner-up. The current 50-seat bonus is a remnant of another era that does not reflect current political realities. Secondly, the party allocation of most parliamentary seats should take place at the district and not the country level. For example, if a party gets 30 percent of votes in a specific district, it should accordingly be assigned about 30 percent of the parliamentary seats from that district independently of its country-wide vote share. A third, and perhaps most important, change should be the breaking-up of large electoral districts that generate incentives for political corruption and clientelistic practices. Breaking large electoral districts into smaller – perhaps even single-member – ones would not only increase transparency and representativeness but also – in conjunction with the district-level allocation of seats – generate strong incentives for parties to form pre-electoral pacts and coalitions (much like the case of municipal elections). Parties that are close enough would have clear incentives to form pre-electoral pacts in order to elect representatives. This, in turn, would mitigate both polarization (the distance between parties’ platforms) and also the ferocity of electoral competition. Moreover, the creation of pre-electoral pacts would increase accountability and voter welfare; voters would have a much clearer menu of options to choose from. For example, if we had had such an Anglo-Saxon type of system during the last elections, SYRIZA and Independent Greeks (ANEL) would most probably have nominated a single candidate in each district while the more moderate pro-EU parties (New Democracy, PASOK and Potami) would have had strong incentives to do the same.

Last but not least, we should note that a system with the described characteristics would make the election of representatives from small radical parties much harder. Hence, the rule would still be disproportional – maintaining the centripetal forces that we desperately need – without an explicit award to the plurality winner. This fact should force non-moderate parties to choose between becoming more moderate (as in Italy where the communists collaborate with other progressive and socialist parties during elections) or vanishing, since they would need to form pre-electoral agreements with other parties to be represented in parliament. This is an additional non-negligible advantage of a single-member-district system over more proportional rules in light of the growing extremism of the political system.

1. Matakos, K., Troumpounis, O. and Xefteris, D. (2015), Electoral Rule Disproportionality and Platform Polarization. American Journal of Political Science. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12235

Konstantinos Matakos is an assistant professor of economics in the Department of Political Economy at King's College London.

Dimitrios Xefteris is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Cyprus.