A push to relabel ‘shark attacks’

On the beaches of Western Australia, by California’s crashing waves and in sight of Hawaii’s blue depths, “shark attacks” are slowly disappearing, at least as a phrase used by researchers and officials.

Last month, two Australian states drew mockery when The Sydney Morning Herald reported that they were moving away from the phrase in favor of terms like “bites,” “incidents” and “encounters.”

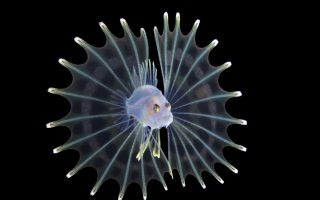

Shark scientists have long called for less sensational language, saying they want to change the public’s perception about animals whose population has plummeted by 71 percent since 1970, largely from overfishing. The disappearance of sharks threatens marine ecosystems and critical sources of food, they say.

Officials in some US and Australian states said they had chosen their language for precision, not political correctness.

“I can understand the sort of pushback to what we’re talking about, as a shift to kind of comical euphemism,” said Catherine Macdonald, a marine conservation biologist and the director of the Field School, a research institute in South Florida. “But I think that some of the shifts being described are actually a push toward greater accuracy and detail.”

Dr Macdonald and other scientists said that shark bites should be described as bites, but that context matters. There are more than 500 species of shark – small and colossal – and people meet them swimming, fishing, surfing and doing other activities.

“There’s a real disconnect between the human imagination of shark attacks and the reality of it,” said Toby Daly-Engel, the director of the Florida Tech Shark Conservation Lab. “A lot of what’s called a shark attack in society is actually provoked by humans.”

People step on small sharks, which snap. Divers have gotten too close. Unprovoked bites sometimes take place in murky water, Dr Daly-Engel said, as when a shark mistakes a surfer for a seal. But bites are extraordinarily rare, she said – globally, there are about 70 to 80 unprovoked bites a year, and about five deaths.

In Australia, the Queensland government offers guidance to minimize “your risk of a negative encounter with a shark.” Western Australia uses “bite” and “incident” in its alert system and sometimes “shark interaction,” if there is no bite.

Most unprovoked bites are reported in the United States, where the shift in language began in earnest in the past 10 years. A Hawaii government website notes that “dog bites” are called “dog attacks” in only extraordinary cases.

Whatever term is used, scientists stressed that sharks are wild and should be treated with caution and respect. The risk of a serious bite is extremely small – people are more likely to die from a bee sting – but shark bites can be devastating.

“If you’ve been in the ocean there was probably a shark near you, and it probably knew you were there even if you didn’t know it was there,” said David Shiffman, the author of “Why Sharks Matter.” Dr Macdonald’s team recently found a great hammerhead nursery off of Miami, for instance.

The shift from “attack” has drawn criticism from the founder of the Bite Club, a support group for survivors.

But Dr Shiffman said the new terms were “about being accurate without being inflammatory. Inflammatory coverage makes people afraid of sharks, and might potentially mean less support for their conservation and potentially support for their extermination.”

[This article originally appeared in The New York Times.]