The slow rehabilitation of a tragic hero

Last Saturday in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, a memorial service was held for a man who died 22 years ago and who, when he lived, was forgotten or, at best, remembered as insane and insignificant. Today, that forgotten Greek is gradually coming to be seen as a martyr in the struggle against colonialism and racial discrimination.

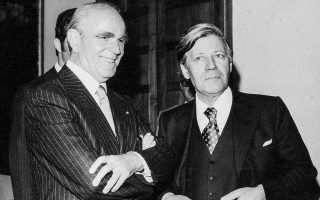

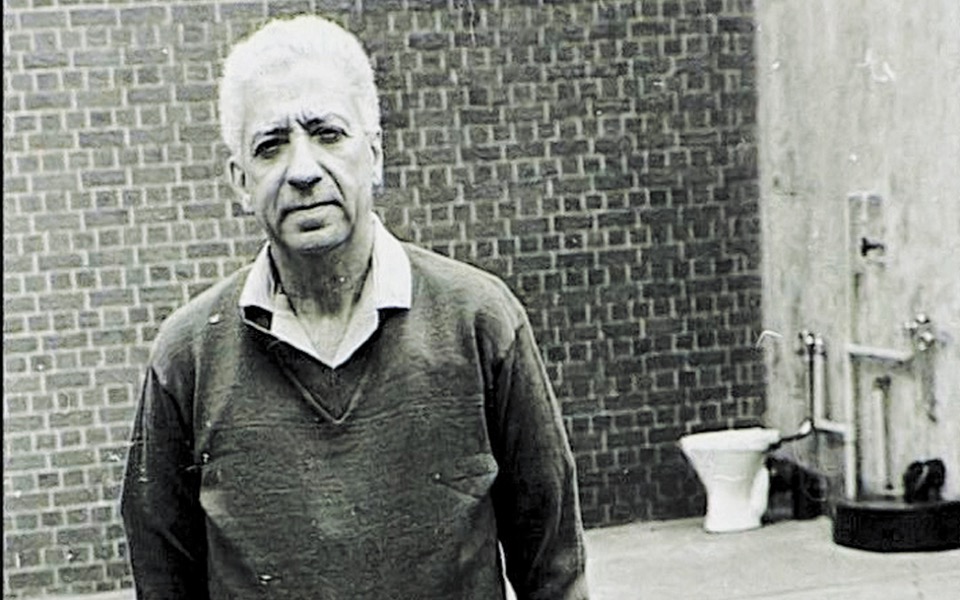

In September 1966, when Dimitri Tsafendas killed the architect of South Africa’s apartheid system, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, stabbing him to death in Parliament, it was almost immediately described as the work of a lunatic who ostensibly carried out the act at the bidding of a tapeworm inside him. The judge at his very brief trial ruled that just as he could not judge a “a dog or an inert implement,” he could not judge the heavyset 48-year-old man before him. Tsafendas was not sent to a psychiatric hospital but disappeared into the harsh prisons of South Africa. When he died in 1999, aged 81, he had spent 33 years behind bars – longer than any other South African prisoner.

Dimitri Tsafendas was born in Mozambique in 1918, the son of Michalis Tsafandakis from Crete and Aimilia Williams, the daughter of a German father and a Mozambican mother. The two were not married. When Tsafandakis married a Greek woman from Egypt, Dimitri grew up with the other children of the family, learning only at the age of 17 that he was not born of the same mother.

The story that was established after the assassination – that Tsafendas was a madman – suited everyone. The apartheid regime would not have to accept that a political opponent had been hired as a parliamentary messenger and had managed to assassinate the prime minister despite the massive security apparatus across the country; Tsafendas escaped the death penalty; the black liberation movement was afraid of the regime’s wrath, especially as Tsafendas had acted alone and it had not had any involvement in the deed; Tsafendas’ family, like all Greeks and other minority groups, wanted the issue to close as quickly as possible so that the hostility toward them would end and they could get on with their lives.

After the end of apartheid, Tsafendas was moved to a psychiatric hospital, where he remained until his death. Very few people attended his funeral. His grave was marked by a stone with a number.

The man who had struck at the heart of a sick regime was himself condemned as being sick. It was this “shabby, old lie” that a young academic from Durham University, Harris Dousemetzis, set out to debunk when he began to investigate the case in 1999. He interviewed 137 people and studied some 12,000 pages of documents in the archives of South Africa, Britain, Mozambique and other countries. In previous years, there had been some references to Tsafendas in a couple of books and studies, and two documentaries (by Manolis Dimelas of Greece and Liza Key of South Africa), which noted that Tsafendas did not appear mentally disturbed. But no one had carried out such a detailed and long examination as Dousemetzis did. Among the revelations was Tsafendas’ statement to the police after his arrest, in which he declared, “I was so disgusted with the racial policy that I went through with my plans to kill the prime minister.” Nowhere was there any mention of a talking tapeworm.

“The more I learnt about Tsafendas’ character, his activism and life-long interest in politics, in particular his loathing of apartheid and colonialism, the more I felt that a major historical injustice had taken place in portraying him to the world as a lunatic and his assassination of Dr Verwoerd as an apolitical and mindless act,” Dousemetzis writes in the prologue of his gripping and very moving narrative of an unbelievable life, one full of political commitment and adventure, “The Man Who Killed Apartheid: The Life of Dimitri Tsafendas (Jacana Media, 2018). “I felt a moral imperative to expose one of the greatest cover-ups in apartheid history and reveal the truth about a brave and humble man who was treated so foully by history.”

Among many revelations, Dousemetzis describes how Tsafendas embraced his (anarchist) father’s love of freedom, listening to tales of the Cretans’ heroic resistance to oppressors. From an early age he began to act against the Portuguese colonial authorities in Mozambique and earned himself a police file. The book details Tsafendas’ travels, his many brushes with the law, and his unswerving commitment to the struggle against colonialism and racial discrimination. Dousemetzis has compiled a 2,192-page, fully detailed report of evidence to the South African minister of justice, asking for the record to be set straight regarding Tsafendas and the political nature of his act. In this, he was assisted by five prominent South African jurists, including the late George Bizos.

The truth about Tsafendas is gradually becoming known.

Last Saturday’s memorial service in the Greek Orthodox Church was conducted by Bishop Ioannis of Zambia (and acting bishop of Mozambique), who, as a priest, had met Tsafendas in prison and has been decisive in helping rehabilitate his memory.

The message that Patriarch Theodoros of Alexandria sent to be read at the memorial is highly significant.

“Despite the efforts to besmirch his character and to describe him as mentally disturbed, Dimitri Tsafendas was a true fighter for human rights, a missionary for freedom and a genuine martyr, having spent the greatest part of his life in prison and suffering indescribable torture,” the patriarch wrote. “We all have a holy duty towards Dimitri Tsafendas, this ecumenical Greek and fighter for freedom, to rehabilitate his memory and to put him on the pedestal that he deserves.”

Among messages read at the memorial service were those from the Communist Party of South Africa, which has pledged to construct a fitting tombstone and monument for Tsafendas, veteran anti-apartheid fighters Ronnie Kasrils and Alex Moumbaris, and prominent jurists.

“He was driven by his passionate belief in classical Greek democracy’s injunction to raise one’s hand against the tyrant,” Kasrils said of Tsafendas. “The tragedy of his life was that his act for freedom was not acknowledged by the liberation movement, even unto this day, and that the falsehood that he was insane created by the apartheid regime was never contested. Tsafendas suffered in agony and in isolation. It is only just and right that he should be remembered as a man who sought freedom and justice for the oppressed and honored as a freedom fighter.”

Moumbaris, who had spent some time in the same prison as Tsafendas, and who escaped after serving six years of a 12-year sentence, wrote: “He is the bravest man I have met. He was a tyrannicide (Τυραννοκτόνος). Glory to his name. I regret that he finished his life in a hospital that looked so much like a prison and only a stone to mark his grave.”