Is Greece really a 6, and Turkey a 7, in their 1-to-10 relations with Russia?

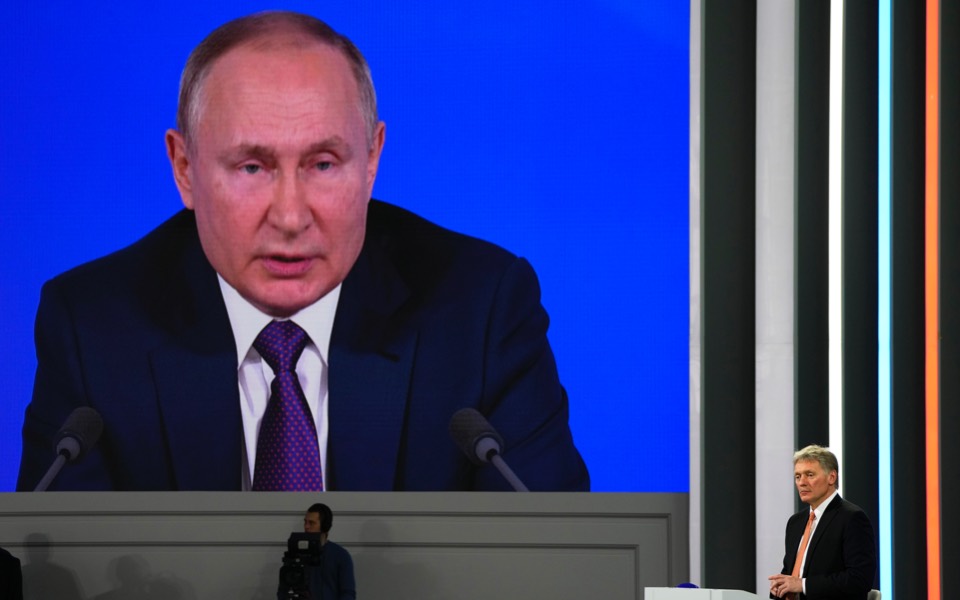

Earlier this month, Dmitry Peskov, Vladimir Putin’s presidential press secretary, was interviewed by Maria Sarafoglou of Antenna TV. Peskov has been called President Putin’s “right-hand man.” He’s a Turkologist, speaks fluent Turkish, and was a high-ranking member of Russia’s diplomatic delegation in Ankara for nearly a decade. Peskov is an important figure when it comes to Russia-Turkish relations. His interview offers insight into the geopolitical significance of Greece and Turkey at a time of rising tensions between Russia and the West. Decisions made in Athens and Ankara are now understood to be part of a higher-stakes conflict.

When asked if Greece would ever be hostile to Russia, Peskov responded, “No, never,” but then underscored Greece’s treaty obligations tethered it to NATO’s hostile expansion toward Ukraine, and Russia’s border. When Peskov was asked to rank Russia-Greece and Russia-Turkey relations from 1-to-10, he gave Greece a 6, and Turkey a 7. While arbitrary, the rankings are illustrative. Peskov asserts that NATO’s deployment of soldiers and military hardware in Greece, particularly Alexandroupoli, is a troubling aspect of Greece-Russia relations. Further on, Peskov critically compared Greece to Turkey, pointing out how Turkey is not fully committed to NATO, while Greece is, “you know, your old friend Turkey, despite being a member of NATO, has very developed relations, militarily and at the technical level with our country. We are undertaking bilateral projects with them, because Turkey is so sovereign that it can take decisions despite being a member of NATO because those are in its best interests.”

Russia and the West face off in various geographic regions, but it is Russia’s geopolitical concerns over the Black Sea region that make Greece and Turkey strategically significant. Russia’s relations with its five Black Sea neighbors are problematic. It is engaged in military hostilities with Georgia and Ukraine, while Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey are NATO members. Russian ships sailing from the Crimean port of Sevastopol must pass through Turkey’s Dardanelles Strait and onward through the Aegean Sea, which is controlled by NATO member Greece. From the Black Sea, Russian gas flows to Europe and Turkey. From Sevastopol, Russia approaches the Mediterranean, the Atlantic and the Suez Canal, while its navy accesses its naval base in Tartus, Syria. Without question, for Russia, the Black Sea is of great strategic importance. Around the Black Sea, Russia and Turkey are mutually interested in keeping extra-regional powers out. By compartmentalizing their relations, Russia and Turkey are engaged in a seemingly cooperative competition. This cooperation arises out of Turkey being a large consumer of Russian gas, and its ambition to become an energy transit hub. As well, Russia is building nuclear-powered energy reactors for Turkey, thereby lifting it to the ranks of a nuclear energy-capable country. Russia and Turkey have also shown a willingness to trade influence in the Black Sea for influence in Syria. The greatest threat to Western interests, however, stems from the strategic military cooperation that Moscow and Ankara are now engaged in.

Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 missile system is a near declaration of independence from NATO. The presence of technologically advanced Russian radars in NATO’s frontier prompted the US to remove Turkey from the F-35 fighter program. Ironically, in one move, Russia obtained a military presence in Turkey, and cleared the Turkish skies of F-35 jets. According to Peskov, Russia is optimistic that its Turkish partners will obtain a second battery of S-400 missiles.

On the matter of Ukraine, President Putin vowed that NATO deployment of weapons or troops there will trigger a response. When asked about Turkish drone sales to Ukraine, Peskov took issue, saying they could embolden Kiev to seek military solutions. Realistically, Turkish drones have no impact on Russia’s ability to overwhelm Ukrainian defenses. Their presence can, however, serve as part of a casus belli for a Russian invasion. In prior statements, Peskov recognized Erdogan could influence Ukraine toward meeting Russia’s demands. Tellingly, Turkey and Russia examine Ukraine outside of the NATO context.

Peskov spoke of a special spiritual, religious, relationship between Greece and Russia. While accurate in the historical context, Moscow is at odds with the Ecumenical Patriarchate. When Hagia Sophia was reconverted to a mosque, the silence from President Putin was deafening. If the Ecumenical Patriarchate were expelled from Turkey, Moscow could claim ecclesiastical leadership of Orthodox Christianity.

When asked about Russian support for Greece in the Aegean and Mediterranean, Peskov reiterated Turkey’s position and recognized the severe effects on Turkey’s national interest. There was no mention or concern for Greece’s rights or national interests. Turkey’s gunboat diplomacy in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean benefits Russia by undermining Cypriot, Greek and Israeli efforts to provide the EU with an alternative energy source.

In contrast to Peskov, Gerard Larcher, president of the French Senate, told Tom Ellis of Kathimerini that the Eastern Mediterranean is not a Turkish sea and that defense agreements providing for French armaments and mutual defense with Greece mean to stabilize the wider region. France’s position is in line with a series of US legislative enactments, such as the Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act, which works to upgrade Greece’s strategic standing in the Eastern Mediterranean. Additionally, the National Defense Authorization Act of 2022 calls for the sale of F-35 Joint Strike Fighter jets to Greece, which with the upgrade of its current fleet of F-16s, and acquisition of French Rafale jets and frigates, Greece’s defense capabilities in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean are greatly improved.

The emerging Russia-Turkey axis is overturning the power balances from the Black Sea to the Eastern Mediterranean – consequently transforming Greece into a NATO frontline state. Viewed in this way, Turkey’s relations with Russia look more like an 8, if not a 9, and Greece a 5, if not a 4.

Andreas Akaras, Lawyer, Business & Government Affairs, Advocate For The Humanities and Science, & Founder Saint Andrew’s Freedom Forum, Washington, DC.