The Times’ landmark shift on the Marbles

The main editorial{ in The Times of London on January 11, describing the case for the restitution of the Parthenon Sculptures to Greece as “compelling,” marked a decided shift in the position held for several decades by the historic British paper – which has been expressing the decision-making establishment for some two-and-a-half centuries – and is much more important than we may think. It cannot go down as just another article in the international press siding with a just Greek claim that dates back to Otto’s time.

Even the most favorable public opinion polls carried out in the UK since Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ visit in November – during which he put the issue to his British counterpart and the public – and even other similarly positive publications like that in The Guardian on February 5 titled “The Parthenon Marbles belong in Greece – so why is restitution so hard to swallow?” cannot compare in gravitas and importance to the one in The Times because this is a paper that has expressed and occasionally even dictated British establishment policy.

Greek history has plenty of examples illuminating the country’s relationship with The Times and how the latter did not express itself just as a historic paper, but as something more than that. For example, it described the British fleet’s participation in the Battle of Navarino as a grave mistake that turned the Royal Navy into a tool of Russian expansion. It was no surprise that shortly after, George IV referred to the battle as an “untoward event.” Later still, following the abduction and murder of Italian and British travelers in Dilessi, The Times lashed out at Greece and called on the Great Powers to step in and take control. In September 1900, meanwhile, Prince George, the high commissioner for Crete, visited the Great Powers to gauge their intentions with regard to Crete’s unification with Greece. In Britain, he was advised to meet with renowned Times Foreign Editor Donald Mackenzie Wallace – later private secretary to the future George V – who even offered to write the prince’s report to the prime minister. Lord Salisbury, in turn, said that Crete’s political status could not change from autonomy to annexation to Greece.

The Times later appeared particularly supportive of Harilaos Trikoupis personally, only to become obsessed – via its Balkans correspondent James David Bourchier – with the idea of a “greater Bulgaria” as a bulwark against Russian expansion to the Mediterranean.

In the post-war era, as the Cyprus issue seriously tested Greek-British relations, The Times expressed the most uncompromising of the Foreign Office’s positions. Its stance on the parliamentary elections in Greece in 1958 is a typical example. But let’s go a little further back. In the fall of 1956, after Britain lost Suez, costing Anthony Eden the premiership, Britain further hardened its stance toward Cyprus, as the loss of its bases in Egypt made holding onto the island even more essential. On December 19, 1956, the House of Commons was presented with Lord Radcliffe’s proposal for Cyprus, which was linked to the secretary of state for the colonies’ famous statement on double self-determination – or, in short, partition. The Greek government rejected his proposal to turn instead to the so-called Foot Plan, named after then British governor of Cyprus Sir Hugh Foot, which was presented to Britain’s cabinet on January 6, 1958.

That was a particularly ominous meeting at Number 10 Downing Street, not because of the Foot Plan, but because Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had that very morning received the resignation of his finance minister, Peter Thorneycroft (later head of the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher), along with two junior treasury ministers, Enoch Powell and Nigel Birch. With the government in a state of collapse, Macmillan admitted in his journal that its stance on the Cyprus issue could not overlook the more uncompromising Tory members who did not want to jeopardize ties with Turkey. The Greek government then rejected the Foot Plan because, among others, it foresaw a Turkish base on Cyprus. So, after two of its plans for resolving the Cyprus issue were rejected, London became eager for a solution. That was exactly when a major political crisis unexpectedly broke out in Greece, when, on March 1, 1958, a no-confidence motion was submitted to the speaker of the House against the government of Konstantinos Karamanlis by 15 of its lawmakers.

Karamanlis described the fall of his government in 1958 as the result of a conspiracy orchestrated by the palace, the Americans, the British and certain close associates of his. “Each sought the fall of my government for their own reasons,” he said. “The foreigners wanted to force me to form a government with the other parties in order to put an end to the Cyprus issue. The others sought to weaken me in a manner that would put me under their control.”

In his book “A History of Missed Opportunities: The Cypriot Problem,” Evangelos Averoff-Tositsas argued that while it was impossible to say exactly what caused the crisis, it was certain it was very artfully encouraged by the agents of foreign governments. He pointed the finger at the British in particular, arguing that despite considerable pressure, the Karamanlis government was not retreating on the Cyprus issue and that a weaker government, a coalition, would ultimately have much less power to resist. “British displeasure in the Greek government was evident from many different signs, because throughout what followed, Great Britain’s stance toward Karamanlis and the National Radical Union (ERE) party was unfavorable. For example, The Times of London, often a Foreign Office mouthpiece, wrote that ERE would get 25% of the vote.” Instead, in the elections of May 11, 1958, Karamanlis won again – with 172 seats!

As for the Parthenon Sculptures, what was The Times’ position until then?

The newspaper itself admitted that until now, it has supported the British government in resisting pressure for the Marbles’ return. On January 23, 1941, Tory MP and later BBC chief Thelma Cazalet-Keir submitted to the House of Commons a question about what legislative measures the prime minister was proposing to adopt “to enable the Elgin Marbles to be restored to Greece at the end of hostilities as some recognition of the Greeks’ magnificent stand for civilization.”

To which Labour Lord Privy Seal Clement Attlee responded that Her Majesty’s government was “not prepared to introduce legislation for this purpose.” Attlee’s apathetic reply was similar in style to another statement made nine years later, in February 1950, by another Labour official, Minister for Colonial Affairs John Dugdale – a Times writer and close associate of Attlee – to the House of Commons on the Cypriot referendum on January 15, 1950 (in which 96% voted in favor of union with Greece): “There can be no question of any change of sovereignty in Cyprus.”

The question of the Parthenon Sculptures was raised again in the House of Commons 20 years after Attlee’s laconic response, when another prime minister, Macmillan, was asked on May 9, 1961 whether the Marbles would be returned to Athens, and he replied: “This is a complicated question which can hardly be dealt with without a great deal of consideration… There is a problem here. I will not dismiss it from my mind, but it raised important questions and would require, I imagine, legislation.”

The very next day, The Times lashed out at Macmillan, ridiculing his relaxed approach and calling on him to give up any idea of their return.

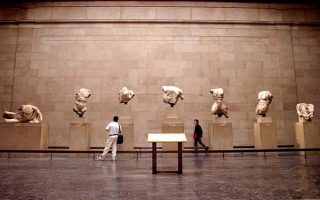

So what exactly can be found in the British Museum, looted by Lord Elgin in 1801 to 1804 and housed following the approval of the British Parliament on June 7, 1816 with 82 votes in favor and 30 opposed? Essentially it is 50% of the sculpted adornments of the Parthenon. These sculpted adornments, from the frieze, the metope and the pediments, present a story, with its own internal continuity. It is the birth of the goddess Athena and her victory in becoming the protector of the city of Athens, it is the Panathenaea processions, the Trojan War and the Gigantomachy, meshing to create the heavenly, temporal and mythical ideological foundations of the new Athenian Democracy, born as a result of the Persian Wars. In particular, the Parthenon’s frieze is the “perfect representation of the ideal of Democracy, as expressed in Pericles’ Funeral Oration,” according to John Beazley, the renowned professor of Classics at Oxford University. Of the 97 surviving pieces of the Parthenon’s frieze, 56 are in London, of the 64 surviving metopes, 15 are in London, and of 28 surviving pediment sculptures, 19 are in London. After the official visit of Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis to London in November 2021, and his successful reintroduction of the question of repatriating the Marbles, The Times, read by more than 1.5 million people every month, admitted that “times and circumstances change. The sculptures belong in Athens. They should now return.” In fact, in an article from February 14, 2022, they suggest that the sculptures could be replaced by 3D marble replicas.

In London, the Greek prime minister said that the issue was political and moral, not legal. The Times, a historic newspaper that has the same motto as the English crown, calls on all contemporary Britons to pursue a lofty, moral and regal act. To what extent will Britain respond?

The British Museum is regulated by a law dating to 1963. Its Board of Trustees comprises 25 members, with 15 appointed by the prime minister, five by the trustees themselves, one by the queen, and the final four are appointed by the Royal Institution. The current legislation allows the trustees to consider an item inappropriate to be held in the museum’s collections. This means it is possible for the trustees to decide, for moral reasons, that it is wrong to maintain possession of stolen property and that it would be wise to return the Parthenon Marbles, reuniting them in an act commemorating the most emblematic work of art of our global cultural heritage. If the trustees consider, based on Article 4 (3) of the 1963 Law, that they cannot release items displayed in the museum, then a change of the legal framework is certainly possible and it is something the British Parliament is experienced in doing. As we said, the issue is political and that is how The Times approached it, recalling the recent return of a fragment of the statue of the goddess Artemis from a museum in Palermo to the Acropolis where it was placed on the eastern frieze of the Parthenon.

There was a swell of widespread international support following Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ visit to London. The Times called on the British government to return the Marbles, as a special case that will not create a legal precedent, to the Acropolis Museum, which is “grand, safe and accessible.” On November 1934, British Under-Secretary of State for Air Philip Sassoon (a Rothschild on his mother’s side), a confidante of Winston Churchill and a supporter of the London museum establishment (as the president of the National Gallery), following a visit to Athens wrote to The Times that “despite the damage caused by the bombs of the Venetians and the Turks, I wonder if in the end the majestic ruins of the Parthenon and the gloried atmosphere of Athens would not be a better setting than the British Museum for the most exquisite marbles in the world.” It seems The Times has decisively adopted the view of the enfant terrible of the British economic and political establishment of the interwar period. The time has finally arrived when Lord Byron may prove to be more persuasive than Lord Elgin!

Konstantinos Tassoulas is Greece’s parliamentary spokesman.