The rebirth of Greek exports

The Greek economy has been experiencing something of a small miracle in the past few years with the rebirth of the country’s exports, something which has gone largely unnoticed because of the rising current account deficit since the start of the pandemic. The causes of this shortfall are very different to those that drove up the external deficit in the 2000s.

Greece at the time had sustained significant losses in competitiveness, which caused imports to rise and exports to stagnate. In contrast, over the past three years, Greek competitiveness has been at a historic high. The 2020-22 current account deficit was due mainly to the plunge in tourism revenues (in 2020 and 2021) and, more recently, sky-high international energy prices. These significant yet ultimately temporary developments stand in the way of appreciating the transformation of the Greek export market.

To be more specific, Greece has become a much more extrovert economy. Based on data from the European statistical agency, Eurostat, exports of goods and services in 2010 accounted for 22% of Greece’s gross domestic product (GDP). In 2021, that almost doubled to 41%. In 2010, Greece ranked last among the countries of the European South in exports of goods and services. In 2021, in GDP terms, it exported more than Italy, Spain and France, and came close to reaching that of Portugal, a country regarded by many analysts as a paradigm of a successful development model shift toward greater extroversion.

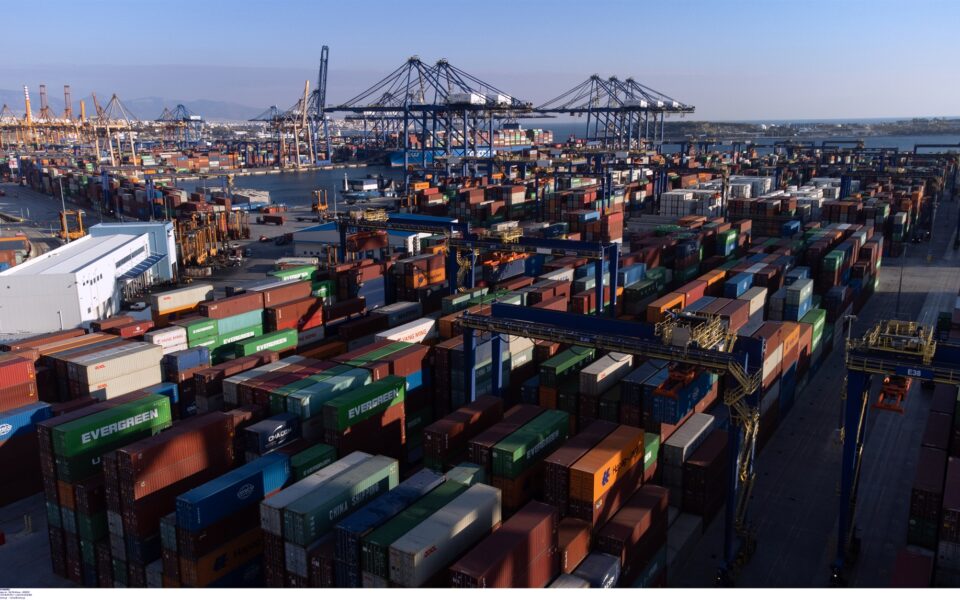

Greece’s exports, moreover, are no longer almost entirely restricted to tourism and transport services. In the past three years in particular, it has made impressive inroads in goods exports. Based on figures published by the country’s statistics office, ELSTAT, total exports in 2010 came to 21.2 billion euros, or 9.5% of GDP, shooting up to €40 billion, or 22% of GDP, last year. In the first six months of 2022, exports of goods came to €26 billion, which is 40% higher than the first half of 2021.

Then we have the fact that Greece’s export base is becoming increasingly diversified. World Bank data show that in 2021 Greece had six categories of goods whose exports surpassed 1% of GDP. Before the Greek debt crisis began, in 2008, it had just one, and that was petroleum products.

Based on figures published by the country’s statistics office, ELSTAT, total exports in 2010 came to 21.2 billion euros, or 9.5% of GDP, shooting up to €40 billion, or 22% of GDP, last year

The country has also made remarkable progress in the export of high-tech products. Here, too, the World Bank reports that in 2020, such products accounted for 13.2% of all industrial exports, a rate that is higher than Italy’s (9%), Spain’s (7.7%) and Portugal’s (7.1%), coming close to that of Germany (15.5%). This represents a deliberate qualitative leap that significantly improves the country’s non-price competitiveness. It is the result of tax incentives introduced in 2013 for investments in research and development, which were increased in 2020. As a result, R&D investments jumped to 1.5% of GDP in 2020 from 0.6% in 2010, contributing to the production and export of high-tech products.

The slowdown of global growth caused by the energy crisis is, without doubt, a bane on the global export market. For Greece, however, the crisis also presents certain opportunities. Europe and the West, more generally, are turning to policies for strategic autonomy, which means repatriating investments from third countries and making major investments toward energy independence.

This substitution of offshoring with nearshoring and friendshoring offers Greece the possibility of attracting a significant number of foreign direct investments (an area in which 2021 and 2022 have seen record inflows of funds) and Greek businesses an opportunity to further increase their share in European and Western supply chains. Thus, the negative income effect caused by the latest international crisis on Greek exports could be offset by a positive substitution effect, substituting foreign products with Greek ones, including in the area of energy.

This requires a further increase in domestic and foreign investments, which, in turn, depends on political stability and the continuation of reforms. If Greece plays its cards right, it may be able to pull off an Irish-style export miracle and become the wonder country of Europe in the years to come.

Michael Arghyrou is a professor of economics at the University of Piraeus and head of the Finance Ministry’s Council of Economic Advisers.