A series of talks between Greece and Turkey, 1978-81

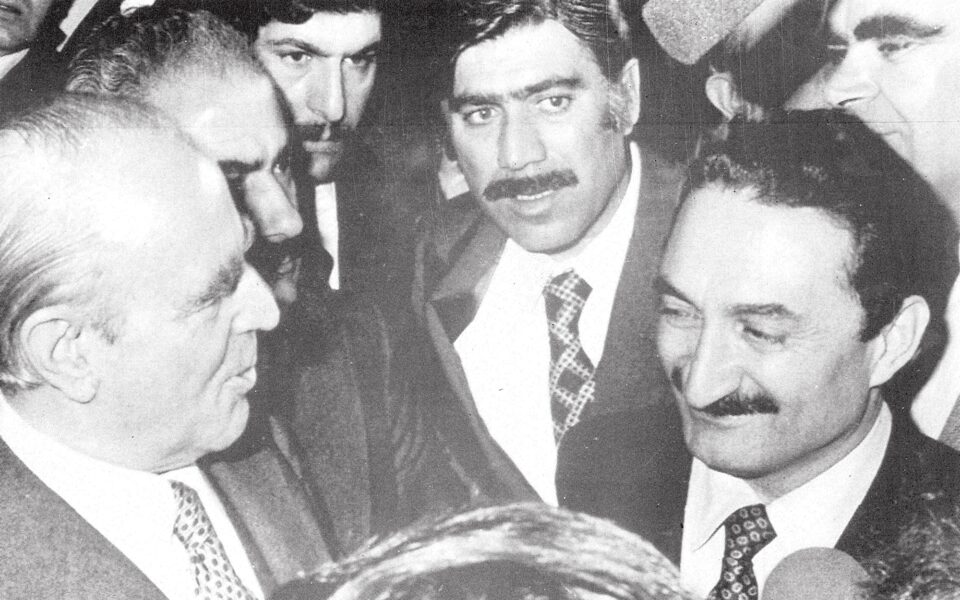

During a summit that took place in Montreux in 1978 between the prime ministers of Greece, Konstantinos Karamanlis, and Turkey, Bulent Ecevit, it was agreed that bilateral talks between the secretaries-general of both foreign ministries would continue. It was an attempt to maintain open lines of direct communication, at a senior level, free of the strain that emerges (or the expectations that are cultivated) when talks are held between political leaders. After all, during the Montreux summit it was made clear that the views of Ankara and Athens diverged on all issues that exacerbated Greek-Turkish relations, with the result that the prospect of reaching an immediate solution seemed unrealistic.

Over a span of some three years, there were a total of nine meetings between the secretaries-general of the two countries’ foreign ministries, Byron Theodoropoulos for Greece and, initially, Sukru Elekdag for Turkey. The first took place in Ankara between June 4 and 5, 1978, with the second following on September 18 to 19 of the same year in Athens. The third was held in Ankara on February 8 to 9, 1979, with the fourth in Athens from July 9 to 10, 1979. The fifth was in Ankara from February 18 to 19, 1980, with the sixth being moved to New York from October 3 to 5, 1980. The seventh moved back to Athens on December 4 to 5, 1980, while the eighth was held in Ankara from March 16 to 20, 1981. The final ninth talks were held in Athens from September 7 to 8, 1981.

Talks focused on three pressing issues. Firstly, the adoption of a political text that would lay out the foundations for a normalization of Greek-Turkish relations (for example, an non-aggression pact or a friendship treaty). The second issue was the delimitation of the continental shelf between the two countries in the Aegean. The talks also focused on issues relating to airspace and air traffic control zones in the archipelago. With the agreement of both sides, issues of minority communities, which were only brought up incidentally (and definitely by exception), were left out of the talks. Additionally, there was no mention of Cyprus, as the longstanding stance of Athens on the issue since 1974 is that Nicosia had the principal role and responsibility in managing it.

Non-aggression pact talks

The idea to sign a Greek-Turkish agreement was based on an earlier proposal by Karamanlis in April 1976. On this foundation, the secretaries-general prepared and exchanged plans for such an agreement, in which were portrayed the different approaches of the two sides. The cornerstone of the Greek plan was a provision for the peaceful resolution of bilateral differences based on international law. Within this framework was included an explicit statement ruling out the use of violence, which after all is something set out by the United Nations Charter. It also highlighted the need to adopt certain practical measures that would help reduce tension and cultivate an atmosphere of mutual trust. What could be considered examples of these were both the commitment that if either country was planning on purchasing new defense equipment to inform the other and providing early warning for the conduct of all medium- and large-scale military drills. The goal was on the one hand to avoid an arms race, and on the other to avoid misunderstandings and unnecessary tensions.

Turkey’s counterproposal was a wide-scale agreement that whether directly or indirectly touched on almost all bilateral issues. For example, the Turkish proposal for the acceptance of the inviolability of the Greek-Turkish border was accompanied by a provision for the “solidification” of both countries’ territorial waters. However, this “solidification” was in fact a diplomatic euphemism to impose on Greece the obligation to never extend its territorial waters in the Aegean beyond 6 nautical miles. Additionally, the Turkish plan referenced the need to limit defense spending; however, it linked it to the geostrategic role of each country. The Turkish officials perceived that as Turkey had increased geopolitical importance, and, by extent, that it should be allowed more leeway in acquiring new military equipment in comparison to Greece. Finally, the Turkish side was working to alter the recognition of the minority in Western Thrace as a national (Turkish) minority, rather than the religious (Muslim) one set out explicitly by the Treaty of Lausanne.

Continental shelf proposals

With the agreement of both sides, issues of minority communities, which were only brought up incidentally, were left out of the talks

The differences in the views held by the two countries were confirmed when it came to the issue of delimiting the continental shelf. Athens vehemently rejected the possibility of trapping Greek islands within a Turkish continental shelf. The most Greece could concede was to discuss the possibility of recognizing the existence of a Turkish continental shelf in the gaps between the Greek islands of the North Aegean, but under no circumstances would it extend any further westward. If this idea was implemented, Turkey would have acquired approximately 10% of the continental shelf in the Aegean in comparison to the 8% that it would acquire if the limit was fixed at the midpoint between these islands and the coast of Asia Minor. Greece consistently proposed that if a solution was not found during negotiations the issue be settled at the International Court of Justice.

As was expected, the Turkish side rejected the Greek proposals. Its main goal, as was confirmed during the successive rounds of talks, was to draw the line between the two continental shelves at the midpoint between the two mainland coasts. According to the Turkish side, the Greek islands of the eastern Aegean that are parallel to the Turkish coastline (from Samothraki in the north to the Dodecanese in the south) are not entitled to a continental shelf. Some effect, but still not a lot, on the determination of the midpoint would only be granted to the islands that are closer to the mainland coast of Greece. If this settlement of the Aegean continental shelf was not accepted by the Greeks, the Turks counterproposed that each country only have the right to explore and exploit areas exclusively within their territorial waters. Apart from that, everything in the remaining areas would be joint ventures between Greece and Turkey.

The two sides also had incompatible views on the issue of air traffic over the Aegean. Turkey sought to decrease Greek responsibility in the Athens Flight Information Region (FIR), as set out by international conventions. In essence, it wanted to divide the airspace of the Aegean into approximately two halves, with Turkey controlling the eastern part. The Greek side rejected the Turkish proposal, stating that if there was to be any change to the Athens FIR then an equivalent change should be made, on the principle of reciprocity, to the Istanbul FIR.

Talks on technical issues (including the conduct of aerial military exercises, the exchange of fighter plane information, and the creation of airways) also proved fruitless. The only positive development was the surprise retraction in 1980 of Turkish NOTAM (Notice to Airmen) 714, issued following the fifth round of talks in August 1974, which had stopped all air traffic over the Aegean.

Overall, the talks held between the two secretaries-general did not contribute anything positive of substance to the course of Greek-Turkish relations. Their utility lies in the maintenance of regular communication between the two sides. That aside, the views of Athens and Ankara remained unchanged. In essence, Greece put forward the need to communicate on the basis of international law, while Turkey’s counterproposal was that might makes right. The two sides did not find even the smallest margin for convergence of views, while frequently the talks got bogged down in the repetition of established views. After all, the secretaries-general did not have the authority to advance the issues beyond what had been set out by each country’s political leadership. Thus, inevitably, they were constrained to a series of innocuous parallel monologues that were stopped by the Greek side when PASOK came to power in October 1981.

Antonis Klapsis is an assistant professor of diplomacy and international organization at the University of the Peloponnese.