Putin and Erdogan share common handbook

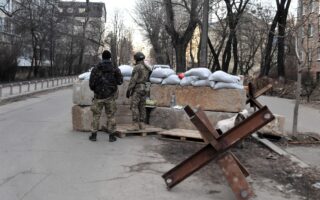

Following Vladimir Putin’s decree, we have entered a third and more dangerous phase of the conflict, with partial conscription and the early referenda constituting an admission of defeat on the part of the Kremlin, seven months after military operations began.

It seems that Moscow rested on the laurels of the territorial gains it made in the first phase of the conflict, when it adapted to its failure to take Kyiv and oust Volodymyr Zelenskyy, seizing control of Donbas (Luhansk and Donetsk), Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. Moscow did not believe that the Ukrainians – in spite of significant assistance from the West, and the US in particular – were in a position to question the faits accomplis created on the ground, and that, instead, they would focus on defending against the loss of additional territory rather than trying to retake some of the occupied areas.

But following Ukraine’s successes in the country’s northeast, and given the serious losses in personnel and problematic planning that led to the removal of a number of high-ranking officers and a drop in Russian morale, Putin’s options were limited. Thus, against the advice of certain of his interlocutors – including Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan – to the effect that he should seek a quick compromise, and in the wake of relevant urging from China and India, he decided to escalate in order to consolidate territorial gains.

The last time he did something along those lines in Ukraine, the predictions were that he would follow the doctrine of “escalation before de-escalation.” These predictions weren’t borne out, so I have serious reservations as to whether it will happen this time either. Besides, leaders like Putin want to show that they are uncompromising, being deluded as to the extent of their power. While a peak in a crisis often provides a window for negotiations, Putin appears to have adopted a “my way or no way” approach.

I fear that in the West, even after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we continue to underestimate not only the resolve of revisionist leaderships, but also their inclination towards an initially regional and later – why not? – global system running parallel to and undermining the existing liberal order. So, if we continue to employ a Western perspective – or unwarranted optimism based on wishful thinking – when interpreting the moves of Moscow and other revisionists on the global chessboard, we risk being hypnotized. Dmitry Medvedev was clear: “The Western establishment – in general all of the citizens of NATO countries – has to understand that Russia has chosen its own path. There is no going back.”

We should hear and read the Turkish leadership in the same way. Because the similarities between the rhetoric and methods employed by Moscow and Ankara against their neighbors and the West as a whole are clearly discernible. And what’s both interesting and problematic is that Turkey is part of the Western world, but over time it is becoming clear that it has lost interest in – or no longer sees the necessity for – showing allied solidarity by backing the decisions of the Alliance. It broke the NATO line with the S-400 purchase and, through its neutral stance on Ukraine, is currently undermining cohesion.

Beyond their authoritarian governing styles, Putin and Erdogan seem to share a common handbook on how to promote/impose their revisionist aspirations. Initially, through threats and intimidation, they try to break their neighbors’ will/resistance. At the same time, they militarize problems, threatening to use force to achieve their goals. This projection of their military might and the sense of post-imperial arrogance lead them to ignore international treaties and the UN Charter, interpreting them as suits their needs. They use hybrid tools (e.g. migration flows in Turkey’s case, cyberattacks in Russia’s) and propagate fake news to legitimize their actions (e.g. Greece is perpetrating crimes against humanity, and Ukraine genocide).

While underestimating their neighbors’ power, Moscow and Ankara paint them as a threat to their national security, not so much on their own, but as part of a plan of powerful states (in this case, the US) aimed at undermining Russian/Turkish sovereignty (because Putin and Erdogan are unpopular in the West). They weaponize minorities, meddling in the affairs of third countries on the pretext of protecting these minorities. They believe they need to correct history and the mistakes of their predecessors, caught up in their own personal vanity. They act like bullies, ignoring diplomatic practice and breaking institutional taboos to show that “anything goes” in the new global environment. They provoke artificial crises for possible future use, but they often find themselves at an impasse, having raised the bar of expectations.

In the end, inciting intolerance and fueling tensions, they project their own intentions and/or potential actions onto their opponents, acting as if they themselves were on the defensive and preparing the ground for a “preventive” counterstrike. This incitement technique is known as “accusation in a mirror” or “mirror argument.”

Constantinos Filis is director of the Institute of International Affairs and associate professor at the American College of Greece. “The Future of History,” edited by Professor Filis, is available from Papadopoulos Publications.