Ideology’s orphans

These days it is as if there are no ideas nor strategies, only the opportunistic use of images and phrases, accusations and fairy tales, whenever this serves the interests of the speaker. Donald Trump might be the world’s opportunist-in-chief, but wherever we turn we see, to some or other extent, political leaders using whatever suits them to achieve their aim, without any plan as to what they really represent or believe – nor what they will do after getting their way. In Greece and Britain we have seen politicians at a loss after their victories, despite triumphal roars, and Italy might follow soon.

The collapse of the Soviet Bloc, globalization and the breakneck speed of technological and communications developments killed off the ideologies that had determined the past century. These same forces grant great power to each group and every individual.

It will be interesting to see the academic studies on the impact of Trump’s tweets on the election, as these brief comments jumped unrefined out of the candidate’s brain at any time of day or night and found millions of receptive readers. Not everyone’s tweets or posts will influence anyone, but this is probably the first time that one person can express himself in such a direct, blunt and sometimes unhinged way and influence so many others immediately. Till now, initial thoughts developed over many years before swaying multitudes; obstacles and new questions that needed answering either strengthened them or killed them.

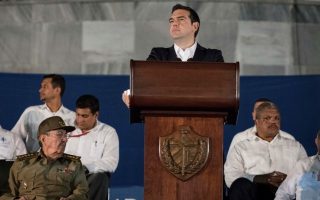

When technology allows us to immediately reject whatever we do not like, this is not ideology at work. When we can laud or damn people or events according to our own interests – when we see Fidel Castro only as a revolutionary hero or as a dictator – we do so according to our own interpretation of things, that which makes us feel justified in our rage or our choices. Because so many of us are doing this at the same time, all day, the field of ideas is broken up, full of noise, images and feelings; it is nothing but an endless, drifting cloud of memories and desires. In this fallout, more and more people seek safety in those who appear most decisive in their aim to achieve power. This “ideology” of the strong dominating the rest is a driving force of politics and can either strengthen democracy (when institutions fight back) or destroy it.

In Greece we are not looking for a strongman. We seek only what is now the luxury of being able to think, to live beyond today. And whereas citizens have become beggars for a little stability, our politicians still strut about like generals in mighty ideological wars.