Contentious geopolitics

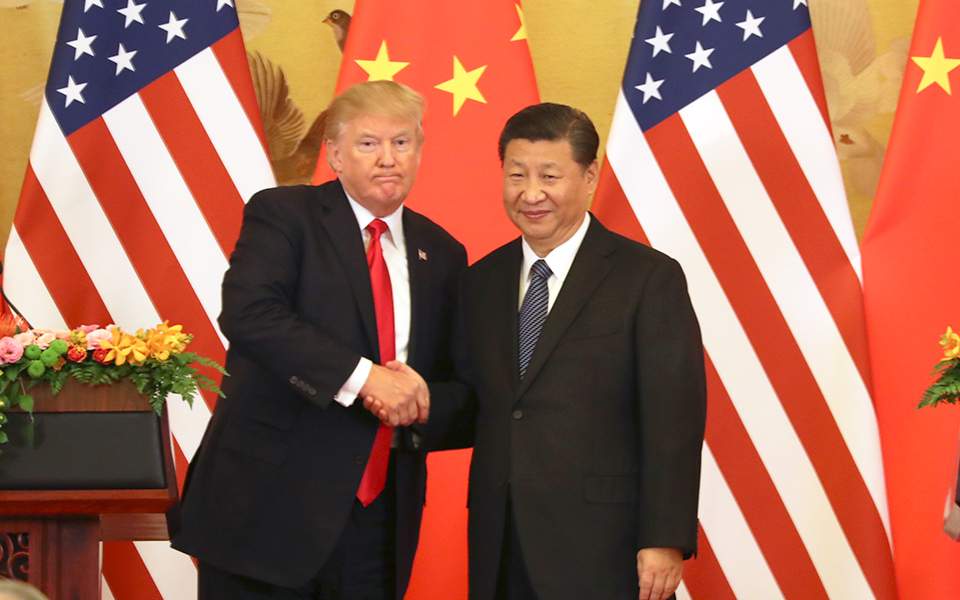

Whatever the current state of the US-China trade war, Asia’s geopolitics are fast becoming more contentious. Presidents Trump and Xi may have made some progress toward compromise at the recent G20 summit in Buenos Aires, but both the substance and timing of next actions remain in doubt, and there's a real risk that Trump, in need of a political win at home, will simply declare victory and walk away without resolving long-term sources of conflict.

In the meantime, Trump’s “America First” foreign policy and his willingness to take trade action against US allies in the region even as he picks new fights with Beijing, have created more space for an increasingly ambitious China to expand its commercial and political influence.

Trump’s explicitly confrontational approach to Beijing resonates with many of China’s neighbors. Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and many others are concerned that China’s growing economic clout is shifting the region’s balance of power in ways that leave them vulnerable. They have good reason to hope that Trump can force China to open more of its markets to foreign products, cut back on subsidies for Chinese companies, and stop forcing the transfer—or stealing—the intellectual property of foreign firms.

But it’s impossible for these governments to consider Trump a reliable ally. Beyond the problem of US tariffs on their goods, his decision to abandon the Obama administration’s commitment to join the Transpacific Partnership—an enormous trade deal that has moved forward without Washington—and his erratic statements on policy all signal they would be wise to hedge their bets on US intentions. It doesn’t help that investigations of his presidential campaign and administration are certain to intensify in 2019, and that it’s not at all clear how the opposition Democrats now think about trade.

In this environment, China will press ahead with its ambitious expansion, and while its investment strategy, centered on its Belt Road Initiative (BRI), has global implications, Beijing’s focus remains squarely on China’s dominance in Asia. Part of BRI’s purpose is to pull the region’s economies closer to China, while boosting Beijing’s strategic influence inside each country. Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Pakistan, Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar have all received substantial Chinese investment in recent months, and the US-China trade war has only increased China’s need to develop new markets for its output and new producers to provide the products that China imports.

Chinese leaders are now well aware that this expansion is creating a backlash in Asia, and elsewhere, as policymakers and companies in neighboring countries see threats embedded in Beijing’s plans. Earlier this year, Malaysian Prime Minister Mohammed Mahathir ordered the cancellation of three Chinese investment projects inside his country and suspended a fourth over concerns they would leave his country deeply indebted. Chinese investment has also become a source of debate in upcoming elections in Thailand and in Indonesia, where a form of Islamist populism is fueling anti-Chinese anger.

In Pakistan, we’ve seen a much more dramatic recent statement of anger directed toward China. Last month, gunmen launched a deadly attack on the Chinese consulate in Karachi. The apparent motive was Chinese investment in a region of Pakistan claimed by separatists. China is a crucial large-scale investor in Pakistan’s economy, particularly as the Trump administration loosens traditional ties with Pakistan’s government. Yet, concerns inside already indebted Pakistan about what China will demand when Pakistan can’t repay its Chinese lenders is on the rise. Call this China’s “debt-trap diplomacy.” It’s a problem more governments are now thinking about.

Even in the Philippines, where President Rodrigo Duterte has actively courted Chinese infrastructure investment, there is a backlash against China’s growing economic reach. Duterte has dropped his country’s territorial claims in the South China Sea, an area where China’s military expansion has drawn international attention, and has so far won little tangible to show for it. As a result, Duterte’s rivals are now accusing him of selling out the country’s interests. It’s an issue that will roil Philippine politics long after Duterte is gone.

Yet, despite the doubts and fears of China’s neighbors, its lasting influence is still Asia’s overriding reality. All these countries need good relations with Beijing—to grow their economies, create jobs, and maintain their political stability. They will manage the risks and opportunities their relationships with China as best they can. What role the United States intends to play in Asia remains the crucial unanswered question.

Ian Bremmer is the president of Eurasia Group and author of Us vs. Them: The Failure of Globalism.