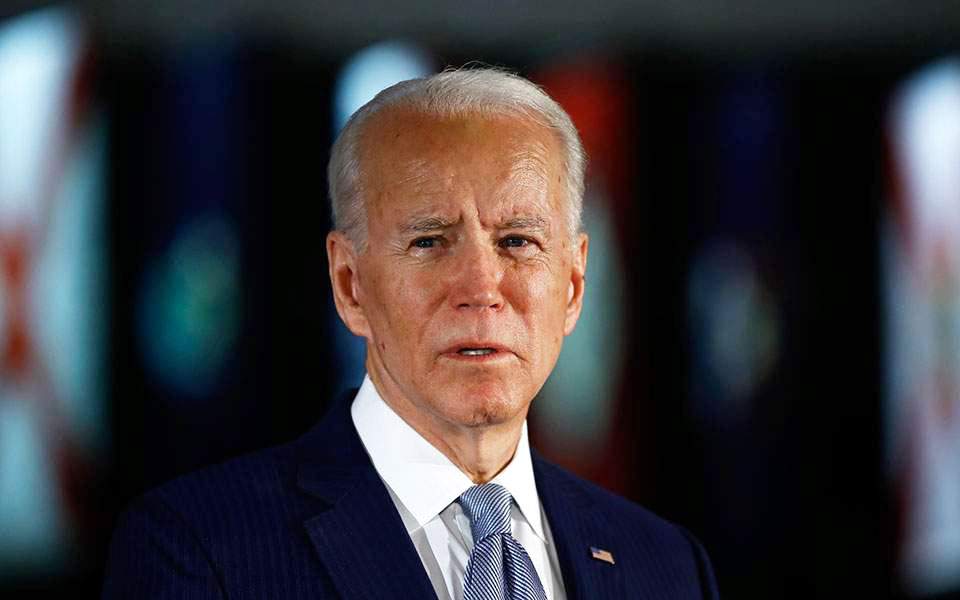

Joe Biden: America’s incoming multilateral, transatlanticist president

In many respects, }Joe Biden is a known quantity on the foreign policy level. A committed internationalist, Biden believes in the value of alliances, treaties, open economies and US leadership. He is a strong advocate of the transatlantic partnership, with an almost perfect attendance record at the annual Munich Security Conference, the equivalent of Davos for defense and geopolitics. His personal relationships with global leaders span across every continent. Having served as both chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and co-chairman of the NATO Observer Group, he was picked in 2008 as Barack Obama’s running mate to complement his then-lack of foreign policy experience. And as vice president for eight years, he had a pivotal role in complex foreign policy situations such as Cyprus, Ukraine and Iraq.

But the world has changed in fundamental ways since Biden left office in January 2017. Populist and nationalist forces have gained power in several countries. Authoritarian leaders have exploited new technologies to become more assertive domestically and internationally. Transnational challenges, including climate change, pandemics, cyberwarfare and nuclear proliferation, have worsened. Meanwhile, America has become increasingly isolationist, with vast implications for multilateralism and international cooperation.

When he is sworn in as president on January 20, Biden will inherit a divided America and a chaotic international order. As such, he will focus on closing the gap between domestic and foreign policy. His primary objective will be to tackle Covid-19 and to rebuild the US economy. At the same time, he will attempt to heal the nation from lasting social and racial unrest, a vicious campaign season, and the horrifying scenes of armed rioters breaching and trashing the US Capitol on January 6. Believing that economic security means national security, he will seek to utilize diplomatic and technological tools to make US foreign policy have a stronger impact on America’s middle class. Geo-economics would play a central role in this effort.

From early on, the Biden administration will signal a renewed US commitment to international institutions and multilateralism. It will rejoin the Paris Climate Accord and the World Health Organization on day one. It will seek to revive the Iran nuclear deal and to agree with Russia to extend the New START treaty on limiting strategic nuclear arms. It will join forces with other nations to halt the spread of Covid-19, while coordinating closely on the development and distribution of vaccines and therapeutics. At the core of this foreign policy agenda will be a global Summit for Democracy that Biden has pledged to convene during his first year in office, aiming to advance human rights and to confront nations that are backsliding – from China and Russia to Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

Revitalizing transatlantic relations would be a key tenet of this strategy. It is no coincidence that Biden’s first international calls as president-elect were with four European leaders – Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, Boris Johnson and Micheál Martin. Biden has signaled that his administration would immediately be ready to forge a new common agenda, stirring the EU-US relationship from a protracted period of antagonism toward a more equal partnership.

Initiating a strategic economic dialogue on trade, tax and technological policy would start the relationship on a strong footing. A symbolic early visit to Europe, perhaps featuring an address before the European Parliament, would showcase a strong commitment to US-European bonds. With three major multilateral convenings all taking place in Europe next year – the G7 in the UK, G20 in Italy, and COP26 (the UN Climate Change Conference) in Scotland – there is scope to present a united transatlantic front on the international stage. Against the backdrop of Merkel’s expected departure later this year, and an increasingly active French foreign policy in and around Europe’s periphery, Biden’s relationship with Macron – which has yet to be developed – will be a key one to watch.

As EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell recently wrote, the Trump era has moved Europe to reconsider its role in the transatlantic alliance, by being more prone to securing its own strategic autonomy, be it on security and defense – subjects that have caused considerable friction in recent years – or on public health, supply chains, and key technologies such as 5G. Reimagining Europe’s role in the transatlantic partnership has the potential to make the relationship more resilient to future shocks and disruptions. This is welcome news for the Biden administration, which needs a stronger Europe to address transnational threats and to effectively deal with China’s growing assertiveness.

Tapping into the recently launched US-EU Dialogue on China, the incoming US administration appears determined to coordinate closely with its European allies – which view China simultaneously as a partner, competitor and systemic rival – to counter Beijing’s digital authoritarianism, unfair trade and investment practices, and human rights abuses, among other concerns. The EU-China investment deal announced on December 30 surprised many in Washington – mostly because of its timing, rather than its content – and even though it is likely to be an irritant in the early days of the new administration, it will not prevent the US and EU from spearheading a new multilateral coalition to balance China. Transatlantic allies are expected to work together from early on to reach common ground on how to appropriately and effectively confront Beijing, all the while maintaining avenues of cooperation to deal with global challenges such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the climate crisis and arms control.

Biden has repeatedly – including in his victory speech on November 7 – called for America to lead “not by the example of its power, but by the power of its example.” The recent images of chaos at the US Capitol – and America’s go-it-alone stance internationally over the past four years – have complicated this task, to say the least. Nonetheless, Biden’s track record as champion of multilateralism and transatlanticism will shape his presidency. It is no secret that his foreign policy will be different to Trump’s. A critical question that remains is how it will be different to Obama’s.

Filippos Letsas is a Washington-based foreign affairs analyst.