As Golden Dawn nurses wounds, far-right newcomer surfaces

European Parliament elections gave observers of the far right in Greece something to smile about as Golden Dawn lost nearly half of its votes compared to the previous EU ballot in 2014. But it was not all good news. As the neo-Nazi party nursed its wounds, the ultranationalist pro-Russia Greek Solution (Elliniki Lysi), a newcomer, staged a surprisingly strong showing, taking 4.18 percent of the vote and one seat in the increasingly Euroskeptic EU assembly.

Support for Golden Dawn dropped from 9.4 percent in the 2014 European Parliament elections to 4.88 percent on May 26. The party’s candidate for Athens mayor Ilias Kasidiaris won 10.53 percent compared to 16.12 percent in the 2014 local elections, while Ilias Panayiotaros, running for Attica regional governor, took 5.59 percent compared to 11.13 percent five years ago.

Inner-party friction appears to be a key reason for the decline of the country’s dominant far-right party. It was most recently illustrated in the decision of leader Nikos Michaloliakos to ditch the party’s three incumbent MEPs and put Yiannis Lagos, a Piraeus MP from Golden Dawn’s old guard, at the top of the party’s EU ticket.

“This sort of party depends on a tight inner circle to survive. Such cohesion can only be ensured by a strong leader,” says Vassiliki Georgiadou, a political scientist at Panteion University who recently penned a genealogy of Greece’s far-right parties.

One of the three EU deputies, Eleftherios Synadinos, left Golden Dawn last year, accusing the leadership of nepotism and corruption. Synadinos, a former army lieutenant general who went on to set up his own nationalist grouping, said he was requested to regularly submit a chunk of his MEP salary to the party coffers.

In September 2013, Greek police arrested Michaloliakos and more than a dozen senior party members following the fatal stabbing of anti-fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas by a party supporter. A month later, Parliament voted to cut off state funding to Golden Dawn on the grounds that its chief and several lawmakers were charged with involvement in a criminal organization. The move deprived Golden Dawn of a major financial resource – an estimated 873,000 euros that year. The number of Golden Dawn’s local organizations gradually dropped from 75 to around 50. Analysts say the impact of that move underscored the significance of institutional checks against political extremism.

“We saw Golden Dawn lose momentum as soon as the institutions took action,” says Georgiadou.

At the same time, judicial proceedings have evidently limited the violent activism of Golden Dawn, frequently accused of attacking migrants and leftists.

“The party could not possibly appear to confirm the allegations while these were being examined by the judiciary,” Georgiadou says.

The trial is still ongoing. The defendants’ testimonies are to begin later this month. Apart from triggering claims of political persecution by party officials looking to attain martyr status, analysts say one cannot safely predict what the impact of a potential conviction would be on the party.

One case study is Belgium’s far-right Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest), the repackaged version of Vlaams Blok (Flemish Block) which dissolved after a court convicted the party of racism in 2004. The regrouping did not prevent the party from staging a successful comeback.

Georgiadou remains cautious about drawing parallels between the two cases. “Charges against Vlaams Blok concerned racist statements. In the case of Golden Dawn, we are dealing with criminal offenses,” she says.

Observers say that even if Golden Dawn were to rebrand itself (the party has reportedly already registered the name Greek Dawn), its outlook would be dim.

“They would need to develop a second body of officials who are not so well known or popular and pass on the power to them. I don’t think that a successor suffering from such organizational shortcomings would be able to sustain Golden Dawn’s current popularity,” Georgiadou says.

New solution, new problem

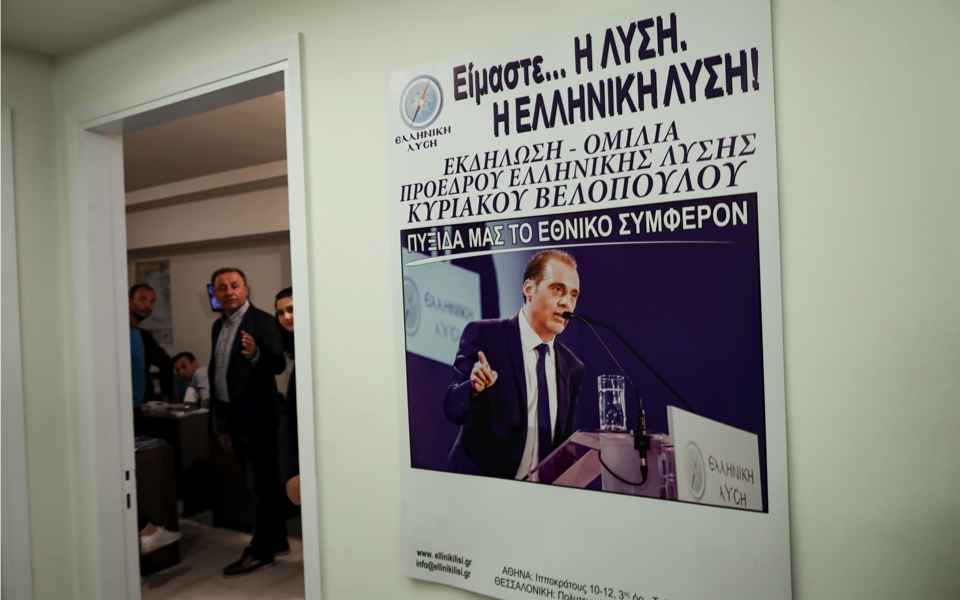

While Golden Dawn took a bruising in European elections, a new force has burst onto the scene.

After electing a representative to the European Parliament on May 26, Greek Solution has set its sights on winning even more seats in the Greek House after a snap election scheduled for next month. According to exit poll data, 12 percent of Golden Dawn supporters gave Greek Solution their vote (another 12.6 percent of Golden Dawn’s voters migrated to New Democracy).

Unlike Golden Dawn, which depended on grassroots action and an extended network of local chapters across the country, Greek Solution is a top-down party built on the back of TV exposure and, some say, Russian funds (the party denies the allegations). Born in Germany to Greek emigrant farmers, its 53-year-old leader Kyriakos Velopoulos was elected as an MP with Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS) in the northern port city of Thessaloniki in 2007 and 2009 before joining the ranks of center-right New Democracy between 2012 and 2015. Velopoulos, a former journalist, is widely viewed as a snake oil peddler for selling items such as “letters written by Jesus” or hair-growth potions on fringe TV programs. His shows are rife with wacky conspiracy theories. In March, he claimed that last summer’s deadly wildfires in eastern Attica were part of a Zionist plot to facilitate the transfer of Chinese exports to Western Europe.

“He should not be underestimated as a mascot,” says Georgiadou, drawing parallels with Giorgos Karatzaferis, who recently stepped down as leader of his TV-based nationalist LAOS party that has failed to recover following its fatal decision to support the Greek bailout in 2012. “Velopoulos is a nucleus. If more pieces are added, you’ll get a mosaic,” Georgiadou says.

Amid the fake news and conspiracy theories, a steadier pattern appears to be emerging, including a Greek-centered analysis of the world, opposition to the European Union, a call for a return to a national currency and an emphasis on national, self-sufficient production. Speaking after European elections, Velopoulos laid out his Orbanesque vision of “a Christian Europe without Islamists.” He added that Greece should lay a minefield and build a wall along the northeastern border with Turkey to stem the flow of “illegal migrants.”

Done deal

Analysts are cautious about the extent to which Greek Solution was boosted by opposition to the name deal signed in June 2018 between Greece and what is now the Republic of North Macedonia, despite the fact that the so-called Prespes accord dominated much of domestic politics over the past year.

“I am not even sure that the Prespes deal remained an issue during the pre-election campaign,” says Georgiadou. “The issue served a strategy and then ran its course,” she says, adding that although played up by the media, reactions were in fact marginal, also in northern Greece.

Figures indicate that hardliners were not rewarded by voters. New Democracy candidate Katerina Markou, a fervent critic of the agreement, performed poorly in the Euro poll, collecting just 29,781 votes – ending up very far behind the party’s top vote-getter Stelios Kymbouropoulos, who garnered 419,759 votes.

If the agreement had had a meaningful impact on the outcome, analysts say, that would also be evident in SYRIZA’s performance. But that did not happen. Exit poll data suggest that the issue failed to galvanize SYRIZA’s left-wing voters. An estimated 5 percent defected to smaller parties left of SYRIZA, including former finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’ DiEM25.

“Prespes is a spent issue. I do not think anyone will invest in it anymore,” says Georgiadou, adding that its trajectory was reminiscent of the clash between the state and the church in the early 2000s after a reformist PASOK government decided to remove religious affiliation from identity cards and to force a referendum on the issue.

Fresh competition

Despite its unexpected showing in European polls, Greek Solution has already been hit by three resignations in the runup to the national election, indicating that the political substance that glues it together is not of the enduring type. However, if the party makes it into Parliament next month, access to state funding would enable it to better consolidate itself also by developing a network of local organizations.

“It may well prove to be a flash party, or not. It’s too early to tell,” Georgiadou says. “One thing we do know though is it will be treated differently from now on. It will be seen as a competitor.”