Greek physician at NASA’s ground control

He was monitoring the astronaut for every second of his spacewalk, intently keeping track of the data on his screen for almost seven hours. He was monitoring his heart rate, his oxygen levels, the amount of CO2 in his helmet, the smallest change in his body temperature. Even his metabolism rate was important, the speed at which the astronaut was burning through his energy reserves. Nothing could be left to chance. When someone is working to repair the International Space Station, you cannot risk fatigue and exhaustion.

In September, French astronaut Thomas Pesquet was conducting another walk into space to continue work on the installation of solar panels. At NASA’s Mission Control Center in Houston, Adrianos Golemis was one of his links to Earth, his own personal doctor. “Directly monitoring medical data from the astronaut’s suit is a very intense experience. At the same time, it is also a great level of responsibility,” he tells Kathimerini. “You have to have the right level of nerves and be aware that you must to make decisions in a very tight timeframe.”

Golemis has been working as a member of the European Space Agency’s medical team since 2018 and is based out of Cologne. In 2019, just after completing his training, he was assigned as the second doctor of Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano’s mission and now he has just finished monitoring 43-year-old Pesquet on his most recent mission. “Aerospace medicine is not a recognized specialty in most European countries. Joining the ESA is a combination of effort and luck, there is no predetermined route,” he says.

He studied medicine at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and later finished his postgraduate degree at the International Space University in Strasbourg. In 2014 he spent a year at the Concordia Station in the Antarctic, where, among other activities, research relevant to space medicine is conducted. In 2018, he responded to the call of the Austrian Space Forum for volunteers and was short-listed for an experiment in Israel’s Negev Desert. If he had made it to the final six, he would have spent a month testing a space suit prototype in conditions similar to those on Mars.

Pesquet arrived at the ISS in April 2021, but his medical observation began in February 2020. “We try to ensure that the astronaut is in peak physical health and is not likely to develop any new illnesses or conditions or injuries prior to their flight,” says Golemis. A special, personalized box is created for every astronaut containing the medications they will take with them to space. “There are conditions that we expect to appear when someone journeys to outer space. During the first couple of days, due to the lack of gravity, there can be issues with orientation. The body is confused, as it does not have the floor as a point of reference, and that can create issues from nausea to headaches,” he explains.

Even blood flow is affected by the lack of gravity. “The human body is made to distribute blood equally. When there is no gravity, more blood moves toward the head, which is why sometimes we see astronauts with swollen faces during their first days in outer space,” explains Golemis.

Emergencies

For the same reason, if cardiopulmonary resuscitation is required in an emergency, the procedure looks nothing like it does on Earth. As the astronaut doctor explains, the lifesaver will have to stand on the opposite wall of the space station, and with straight legs and extended arms press on the patient’s chest. Any conventional attempt at chest compressions will fail, for as long as they are in orbit the person doing the resuscitation will not be able to take advantage of their own bodyweight.

Golemis has yet to be called upon to manage an emergency situation. However, the ESA, in cooperation with NASA, is always ready for the unexpected. Even if someone exhibits an extreme allergic reaction, they are ready to guide the other astronauts in helping save their life.

The human body in space

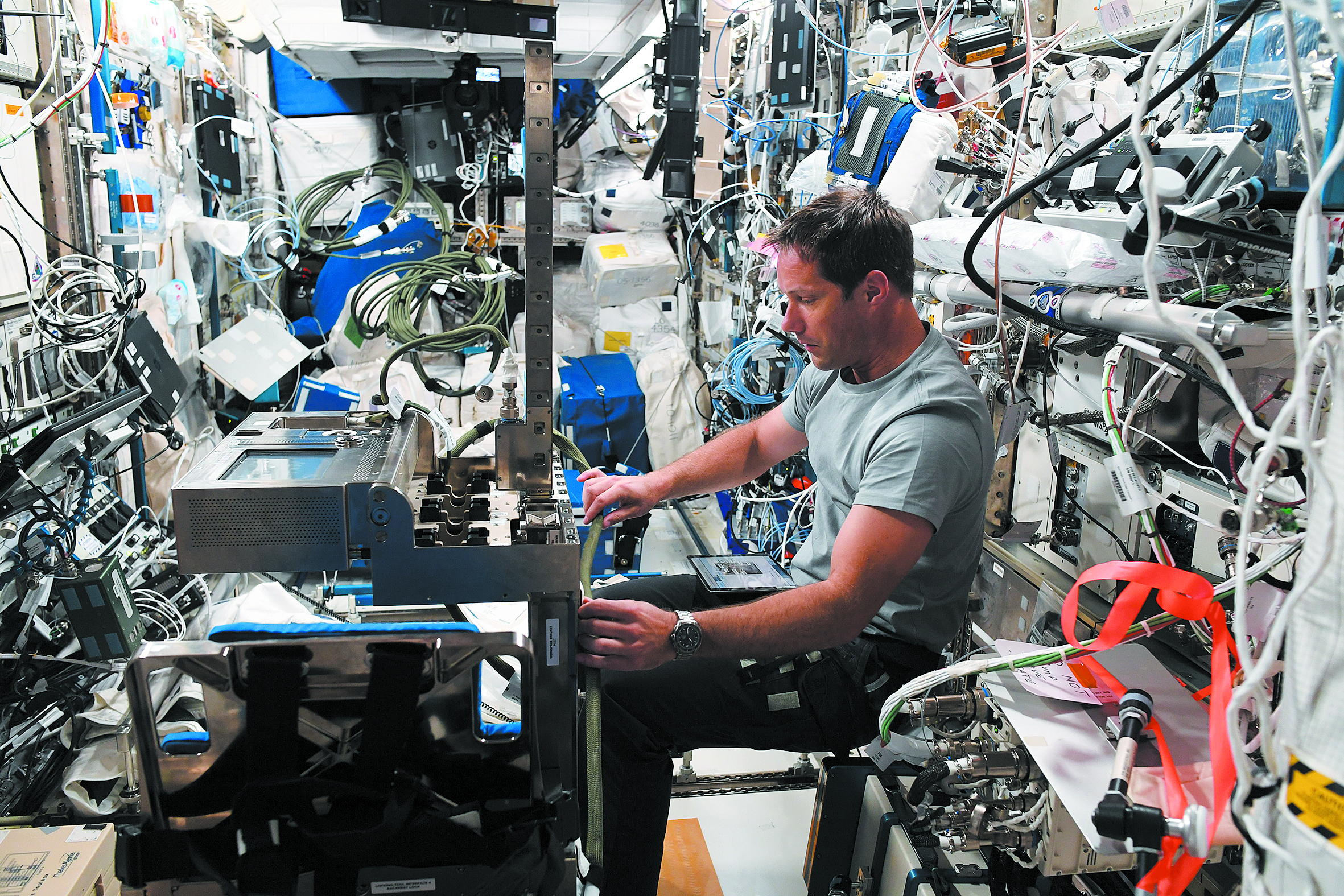

French astronaut Thomas Pesquet returned to Earth on Monday. While he was at the ISS he and Golemis got in touch once a week for a remote clinical assessment. “Our role is to monitor and evaluate the results of the preventive medical exams that are conducted in orbit and to give guidance if any other issues arise,” says the 34-year-old doctor. “At the same time, we help with other issues relating to the astronaut’s psychological condition. It is not sustainable to continually ask someone who is isolated in outer space for so many months to carry out so many tasks in a day. We are there to protect the astronauts from being pushed beyond their limits, potentially risking their health.”

Beyond Golemis, the medical staff includes a psychologist, biomedical engineers, and physical trainers and physiotherapists. During the mission they can monitor the astronaut’s hematocrit, and they conduct stress tests two or three times in a six-month period, the usual length of a mission. “In outer space, muscle mass and bone density are diminished, as are the heart’s capabilities sometimes,” explains Golemis.

Astronauts are also called on to examine their eyes using ultrasound technology two or three times over the same period, as it is possible they might develop spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS), a condition of the eyes’ nervous system. After an extended stay in outer space and zero gravity, some astronauts are affected by sight problems that usually subside following their return to Earth. However, the symptoms can persist.

Radiation

The impact of outer space on the human body does not stop there. Anyone keeping track of an astronaut’s health must take care to monitor their exposure to radiation. “On Earth, due to its magnetic field and the atmosphere, we are sufficiently protected from radiation,” says Golemis. “However, when someone is at an altitude of 400 kilometers, which is where the ISS is, they are exposed to more radiation. And after so many months in orbit it adds up. To deal with it before it becomes an issue, every astronaut must not go past a certain level in their career, to avoid future risks of developing cancer or cardiovascular disease.”

A colleague of Golemis was at the spot where Pesquet landed on Earth. The Greek doctor awaited the astronaut’s arrival in Houston and traveled with him to Cologne in a plane stocked with medical equipment. What will now follow is a period of rehabilitation.

“It usually requires a minimum of three to four weeks for an astronaut to readjust to life back on Earth,” says Golemis. “The readjustment is not an easy process and, in some way to a smaller degree, I experienced it too following my return from the Antarctic. We must ensure that an astronaut who returns from space will have time to spend with their friends and family. That is very important.”

The issue of communication between astronauts and their families was particularly difficult for the medical team due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Before vaccines became available, they had to weigh the risk of infection from the new virus and judge whether an astronaut could visit his family during his downtime while preparing for the mission.

Golemis is hoping to go on a spacewalk of his own. He has already responded to the recent call by the ESA for new astronauts. Over 22,000 people have replied in total, with 280 from Greece. “Without a doubt, I want to be where they are,” he said.