A warm embrace for Ukraine’s children

How the coordination of different stakeholders in Athens and Kyiv has allowed 10 young orphans to escape the war and find safety

Just before midnight on Good Friday, Heracles Moskof, Greece’s special secretary for the protection of unaccompanied minors, called Sofia Kouvelaki, CEO of The HOME Project, an organization that supports unaccompanied child refugees, to announce the news: “The children have just crossed the border at Promachonas [in northern Greece],” he told her with great relief.

Moskof hung up and figured he might squeeze in a few hours’ sleep before meeting the youngsters. But it wasn’t to be: Every hour, the chief police officer of each region the bus carrying the Ukrainian children passed through would call him, informing him of their progress.

At 5 in the morning, they called him again to tell him the bus had reached its destination, the shelter of The HOME Project. “But we are here, and we do not see it,” he replied anxiously, as he waited with Kouvelaki. As it turned out, the bus was parked 100 meters away because the road was too narrow for it to approach the shelter. They ran toward the bus, the driver opened the door and, one by one, the little ones emerged. They were exhausted from the long journey and one of the girls, just 4 years old, stumbled, fell and started crying. They hugged her and her tears immediately stopped, giving way to a big smile. It was a very moving moment for everybody, after two months of persistent efforts, the first 10 orphaned children from Ukraine had just arrived in Greece, and they were safe.

When Kouvelaki and Moskof first discussed the issue, it was at the outbreak of the war. They spoke to Deputy Minister of Migration and Asylum Sofia Voultepsi and informed her about the data they had received from war-torn Ukraine: “Some 170,000 children were in institutions or foster families. They were at risk. In Greece, there are 300 empty places at child protection organizations. We can help them and host them,” they told her. Voultepsi agreed and spoke to the prime minister. “Of course they are welcome. If you need any help, just tell me,” Kyriakos Mitsotakis said. Voultepsi, Moskof and Kouvelaki immediately got down to work. Back then, of course, they could not have imagined how difficult the project was going to be.

From the beginning they followed the prescribed procedures based on protocol, and in close cooperation with the Ukrainian Embassy in Athens they got in touch with the ministries and other authorities concerned. Voultepsi remembers one of the first web conferences she and Moskof had with two Ukrainian ministers responsible for child protection. As they were talking, they suddenly heard air raid sirens. The two Greeks froze. “Do you maybe want to stop?” they asked. “No, we continue,” the Ukrainians responded. They thanked the Greeks for their interest and told them about the rumored horrors that other big organizations have confirmed: In regions that fall under Russian control, children disappear and are taken to Russia. “We know that they will be safe in Greece, but we do not want them to spread all across Europe and to lose track of them. They have to be accompanied by people we trust,” they told them.

The very next day a memorandum of cooperation was signed in which the Greek side committed that the children were not to be given up for adoption and that they would return when the war ends.

Ranging from 10 months to 17 years old, these children had either lost their parents or their parents had permanently lost custody of them before the war even broke out

After that, at three different times, there was information that a group of children – each time a different group – would arrive. But something would always happen at the last minute and the mission would be canceled. In the middle of a war, with all humanitarian corridors closed and without child protection mechanisms, no one was ready to make the decision for the children to leave the country.

As the weeks went by, Kouvelaki and Moskof realized they had to take action outside the strict protocol. They contacted dozens of people in Ukraine. From the metropolitan of Kyiv to Ruslana (the 2004 Eurovision winner who had taken on the role of the ambassador of child protection), not to mention people in the field who had a clear picture of the conditions and the needs at specific orphanages. That’s how they learned about the orphanage from where the 10 children finally came to Greece: Ranging from 10 months to 17 years old, these children had either lost their parents or their parents had permanently lost custody of them before the war even broke out. But the problem was that their caregivers had to stay behind with the other children at the institution, so an appeal was made in the area in order for three nursery teachers who would accompany them to Greece to be found.

When they were found, the phone call that everyone was waiting for was made to Greece. The children, they said, should leave immediately. It was Holy Wednesday and at the ministry they began to organize the evacuation. The original idea was to organize air transport – an airplane would be rented with the help of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). But time was of the essence and finally the solution was given by a contact of Voultepsi in Ukraine: the expatriate Pantelis Boubouras, who undertook the transport of the children with a bus, and two drivers who would drive alternately for 33 consecutive hours without stopping.

The journey

On Holy Thursday, 16 people boarded the bus (the children of the caregivers also came to Greece). Each orphan carried with them a small suitcase with a few clothes and a folder with their history. Only the 10-month-old had a few toys to play with during the long trip. They did not know a lot about the country that would host them. They said farewell to the staff at the orphanage and the bus set off. People in both countries were carefully watching the progress of the bus online until it was out of the areas that were being bombed.

Meanwhile, the team of The HOME Project had 48 hours to reorganize the shelter that would host them: to find staff, basically translators, as they did not speak English, but also to make internal changes in the shelters so that all 16 people from Ukraine could stay together.

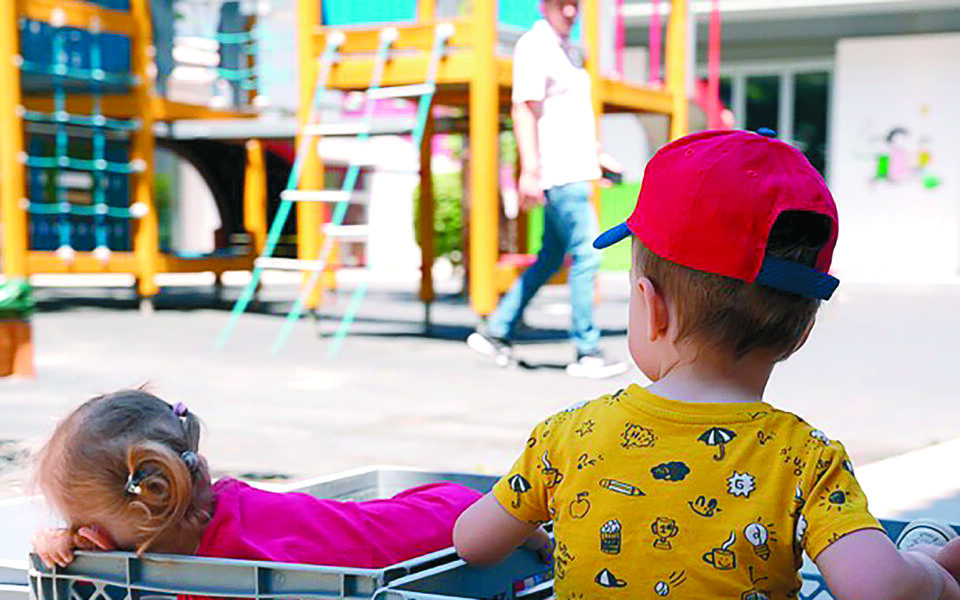

Kouvelaki herself spoke with nine boys staying at one of the shelters funded by the Dutch government and run in cooperation with the NGO Movement On The Ground and explained to them that unfortunately they would have to separate and move to another shelter. She had been worried about how they would take it and was very moved by the support they showed: While leaving they left gifts and cards for the new children. Since then, they have visited them often, playing with the little ones and sharing their own stories with the older children. They had also experienced war and migration and had made equally dangerous journeys – completely on their own. Their coexistence in such a safe and supportive environment is therapeutic for all.

The adjustment

The children from Ukraine have already been in Greece for a month. Although the school year was almost over, Kouvelaki spoke with the Moraitis kindergarten, and two twin boys had the opportunity to start attending the school. Their teacher, Klio, taught her students the Ukrainian words to welcome them and they have adapted so well that they have already suggested they don’t need the caretaker to stay with them at school. The three youngest attend the “Little Angels” kindergarten. There, by chance, was a pupil of Ukrainian origin, and his mother helps out voluntarily with translation. The older kids attend courses in the Ukrainian school of the Ark of the World, but also through distance learning, which continues in their country so children don’t miss the school year. All 10 children participate in all of The HOME Project activities with other children at the hostels. On the weekends the oldest of the 10 attends courses at American Community Schools of Athens (ACS Athens), while the smaller ones play at the Moraitis School. Day by day, the people of the shelter are seeing them opening up and making new friends. There is frequent communication between The HOME Project and the orphanage in Ukraine, but also between Moskof and the ministry in Kyiv. And while it initially focused on these 10 children and the plan that they would probably return to their country in September, last week they first broached the idea that more children could come to Greece. In a teleconference at the ministerial level, the message was clear: Unless children from institutions are immediately moved somewhere safe, they are in danger of being lost.