The mysterious ‘frying pan’ of Syros

The history of Greece is inextricably linked to the sea. Greek mythology is awash with stories of maritime adventure, naval campaigns, and the Aegean peoples’ insatiable quest to procure new materials: Heracles’ journey to Gibraltar (the “Pillars of Heracles”), Jason and the Argonauts’ voyage to Colchis in the Black Sea, and, of course, Odysseus’ wanderings around the Mediterranean, to name a few.

While intrepid seafarers have been exploring the islands of the Aegean since the end of the last great Ice Age, in search of new food resources and raw materials, permanent settlement of the Cycladic islands took place much later, from the mid- to late-5th millennium BC. At this time, seafaring farmers introduced cereal crops (emmer wheat and barley) and domesticated animals (sheep, goats and pigs) to the islands, establishing the Neolithic (or “New Stone Age”) way of life; an extraordinary feat considering the paucity of fresh water.

These early settlers constructed small villages of stone-built houses on Saliagos, Naxos, Mykonos, Thera (Santorini), and Kea, and worked and distributed obsidian (volcanic glass), pottery and marble along sea routes that connected the islands, sowing the seeds of development for a subsequent Cycladic culture that flourished in the Early Bronze Age, from 3200-2000 BC.

Best known for its enigmatic art, including otherworldly-looking marble figurines, with folded arms and slanting heads, Early Cycladic culture has been baffling and exciting archaeologists in equal measure since the late 19th century.

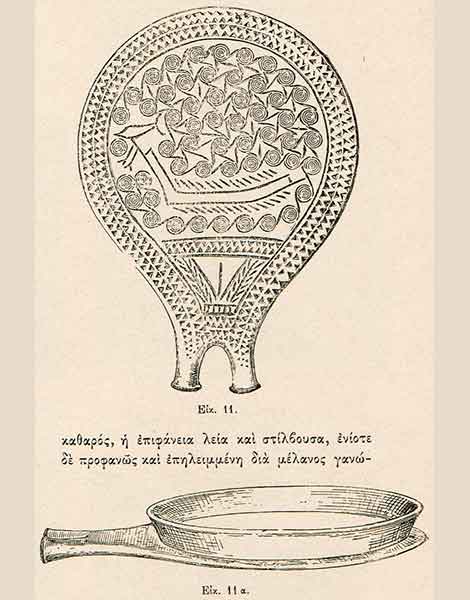

The term “Cycladic civilization” was first coined by Greek archaeologist Christos Tsountas, who investigated burial sites on several islands in 1889-1890, inlcuding a major cemetery on Syros. It was here, amid 600 tombs at a site called Chalandiani, that Tsountas and his team uncovered a mysterious earthenware object in the shape of a modern-day frying pan, or skillet.

Fully intact, apart from a partially broken rim, the underside or reverse of the object was found to be deeply incised with an elaborate decoration, featuring a longboat with 28 oars/paddles and a tall prow, voyaging across a sea of swirling, frothing waves. One of the most striking aspects of the decoration is a fish ensign and two banners surmounting the high prow, perhaps a decorative figurehead or wind vane. Above the two-pronged handle on the bottom, without any apparent relevance, is an engraved pubic triangle, separated from the main decoration by a chipped border.

The connection between female genitalia and seafaring has baffled specialists for years, with some suggesting a link between the sea and fertility; that maritime connectivity between island communities would have been essential to the success and continuity of early Cycladic society.

What was it used for?

The object was one of at least ten similar “frying pans” with ship motifs discovered at Chalandiani on Syros. As grave goods, archaeologists have suggested the objects may have reflected the social status of the dead occupants as shipowners or renowned mariners in life, the depictions being the work of a handful of highly-skilled artists.

There have been multiple explanations as to the use of these so-called frying pans over the years. Archaeologists have variously suggested they were used as decorative items, religious or ceremonial objects, plates, or even as simple cooking utensils – actual frying pans. Their form, shallowness and flaring sides would have also been appropriate for use as a kind of mould, in which liquid could set solid, or as a vessel to process sea salt, a highly valuable and tradable commodity. The one problem with the functional object theory is that none of the nearly 150 frying pans discovered in the Aegean region to date show any signs of wear and tear.

More recent theories based on experimental studies have suggested they have been filled with water or olive oil and served as mirrors (mirrors often featured as grave goods in much later Greek burial customs). Highlighting the frequent depiction of female genitalia, another interesting theory is that they were synodic calendars, the swirling symbols and decorative motifs indicating the movement of celestial objects, and used by women as pregnancy predictors and due date calculators. Proponents of their use in Early Cycladic ritual and religion also suggest they could have functioned as receptacles in fertility rites. In any case, it is widely accepted, given their rarity, that frying pans were prestige items.

Assigned the inventory number “NAMA 4974,” this particular frying pan an exceptional example of the so-called “Syros type,” dating to 2800-2300 BC (the Keros-Syros culture). Measuring 20.2cm from tip to the base of the handle and 20.1cm across, this fascinating object can be seen on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, in Room 4 of the Cycladic Antiquities collection.

This article first appeared in Greece Is (www.greece-is.com), a Kathimerini publishing initiative.