The Greek defending the rights of Aboriginal Australians

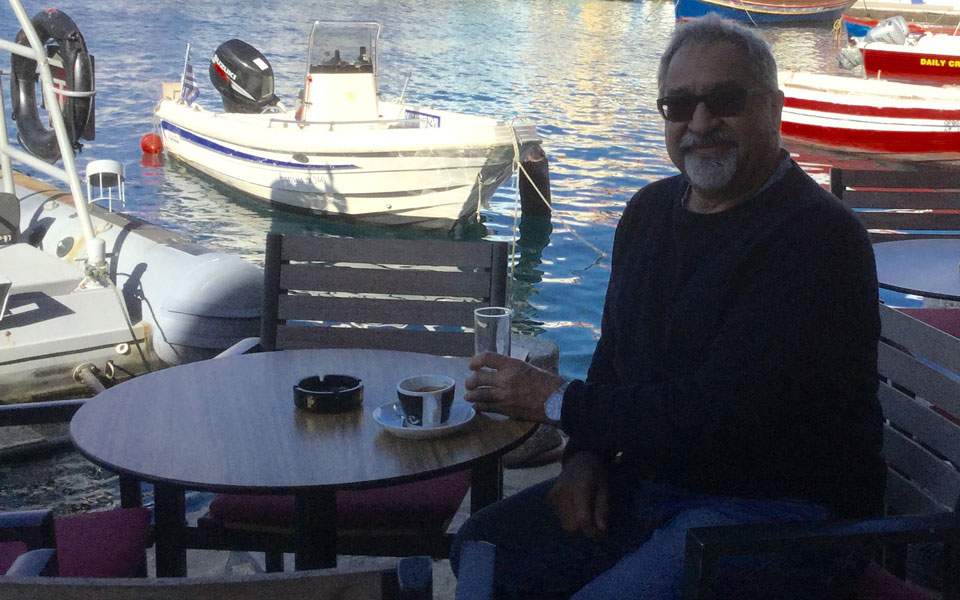

Andrew Jackomos is fighting to improve the living conditions of young members of the Koori tribe, indigenous Australians of New South Wales and Victoria. Still, when the 65-year-old walked around Kastellorizo, the island from which his grandfather emigrated, he felt a sense of awe. “My heart is shared between all of my ancestors,” Jackomos tells Kathimerini. “I am equally proud of both my ancestries.” His mother, Merle, was from the tribes Yorta Yorta and Gunditjmara, while his father, Alick, was the son of Greek immigrants.

Jackomos spoke a couple of months ago at a special Greek community event in Melbourne about what connects the two communities. “I walked where my ancestors walked, swam where they swam,” he said, speaking about his trips to Athens and Kastellorizo. “Eating in local tavernas, I was reminded of the flavors of my Greek grandmother’s cooking.”

According to Jackomos, the Greeks and Aboriginals have had similar experiences with foreign conquerors. Their common fate as “undesirables” brought the two communities together at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, and it was the power of love that then drove (and continues to drive) many people to interracial marriages.

Today a father and grandfather, Jackomos has been an independent commissioner at a national level for Aboriginal children and young people in Victoria since 2013. In these four years, he has written two heavy-hitting essays: “Always Was, Always Will Be Koori Children” and “In the Child’s Best Interests” (2016).

In those essays he records in great detail and with great eloquence the lives of Australia’s young Aboriginals, so often marked by dropping school enrollments, heavy drug use and violence. Several local studies have found that marginalization is particularly acute in youth detention centers for Australia’s Aboriginals, reminiscent of decades long past.

“As a form of punishment they take away pictures of their families, which they keep as a memento in their cells, as well as toilet paper and soap,” Jackomos says, aiming to raise public awareness and sway public opinion.

Days-long isolation and other forms of physical punishment are common.

According to Jackomos, delinquent behavior, especially among Aboriginal boys, is the result of psychological trauma passed down through the generations and stemming from the harsh politics imposed during the colonization of Australia’s Aborigines.

“Because so much remains the same, the trauma does not have a chance to heal, but instead grows deeper,” he stresses.

The only way, according to Jackomos, to combat the above ills is for children to stay close to their schools, their culture and their family.

Those who know Jackomos’s family history are not surprised by his commitment to this cause, as he has taken over from his father, considered a hero among Australia’s indigenous peoples for fighting – together with his wife – to secure rights for all Aboriginals.

The Jackomos family migrated from Kastellorizo to Australia – first Perth, and then Melbourne – at the beginning of the 20th century. Like many Greek migrants, the family got involved in the restaurant business, running a fish ‘n’ chips shop. Alick was born in 1924. Growing up in the neighborhood of Fitzroy, he developed connections with the Aboriginal community. Later, he fell in love with and married Merle. A year later Andrew was born, followed by two more children.

The 65-year-old still remembers helping his father collect signatures for the referendum in 1967, a turning point in Australian history, as it recognized Aboriginals as equal citizens and abolished racist laws, such as one which would not count Aboriginals in the population census.

Alick Jackomos, who died in 1999, is remembered because even though he was not an Aboriginal, he was embraced by the community, which he supported at every level at every step of the way. Along with his activism, equally impressive is that despite leaving school at the age of 12, he worked as a folklore archivist, documenting Aboriginal family history and stories. His autobiography “A Man of All Tribes: The Life of Alick Jackomos” is considered essential reading for those who wish to celebrate modern Aboriginal history.

The relationship between the first Greek migrants and the natives of the distant continent has been described as harmonious, as both communities felt equally isolated by the policies of “white Australia.” In fact, when Andrew Jackomos was asked if he is the only Greek Aboriginal, he responded with confidence that in the 1930s and 40s there were more Greek men who married Aboriginal women.

“I have, after all, found someone who shares my last name,” he said. “I haven’t met him. I don’t know if he has roots in Kastellorizo.”

In the same way that the commissioner of Greek heritage searched for his family’s past, descendants of those interracial marriages are seeking to reconnect with their roots, while many are also keen on learning the languages.

“Unfortunately, I haven’t learned Greek, nor the language of the Aboriginals, but it’s never too late,” he concluded. “I recently learned from the vice president [of the Greek Community of Melbourne and Victoria] Theo Markos about Greek lessons organized by the community.”