A visual history of Greek Australians

Through their visual project “Greek Australians: In Their Own Image,” Australian documentary photographer Effy Alexakis and her historian collaborator Leonard Janiszewski have shone a light on a kind of Greek-Australian history that few are familiar with, with more than 2,000 recorded oral history interviews as well as various types of documentation.

The two met while studying fine arts and archaeology at Sydney University and have continued charting their own path since then. Photography has become more of a passion for Effy while Leonard was already into the history of Australians. When Effy’s father died, she had been undertaking a postgraduate diploma in professional art studies – photography, in particular. After her graduation, she spent six months traveling, visiting her relatives and getting to know Greece.

The couple have published three books together, “Images of Home” (1995) and “In Their Own Image: Greek-Australians” (1998), published by Hale & Iremonger, “Greek Cafés & Milk Bars of Australia” (2016), published by Halstead Press, and are now working on a second volume of the latter.

“My parents migrated here in the 1950s. I have worked as a photographer for my whole career, mostly for Macquarie University. I like to call myself a Greek Australian,” Alexakis says. “Due to racism, you can never fit in and one part of me wants to take the hybrid option and identify myself as Greek Australian. I assume a lot of people that are from my generation are the same. We are not Australians and definitely not Greek, so we fall somewhere in between. Greece makes you feel comfortable and feel alive; Anglo culture is not like that,” she says.

I am curious about the way you describe the project “Greek Australians: In Their Own Image.” How did the project start and evolve with your best friend and partner Leonard Janiszewski?

Effy Alexakis: My parents came in the 1950s, and while we were growing up, they had the idea of making some money and then going back (like many returned Greek Australians did). And I think that’s typical of the migrant story here. When we interview people, they always say that they were planning to come and to work for a few years and then go back. So when my father died quite young – he was 55 – I think it cemented the idea that we would not go back and we were Australian. Growing up, we were always told, “You are Greek.” It was really hard to live as a Greek in a country like Australia, where you wanted to fit in, to belong. For my mother’s generation, as a first generation, she didn’t belong to Greece anymore, and never belonged here either.

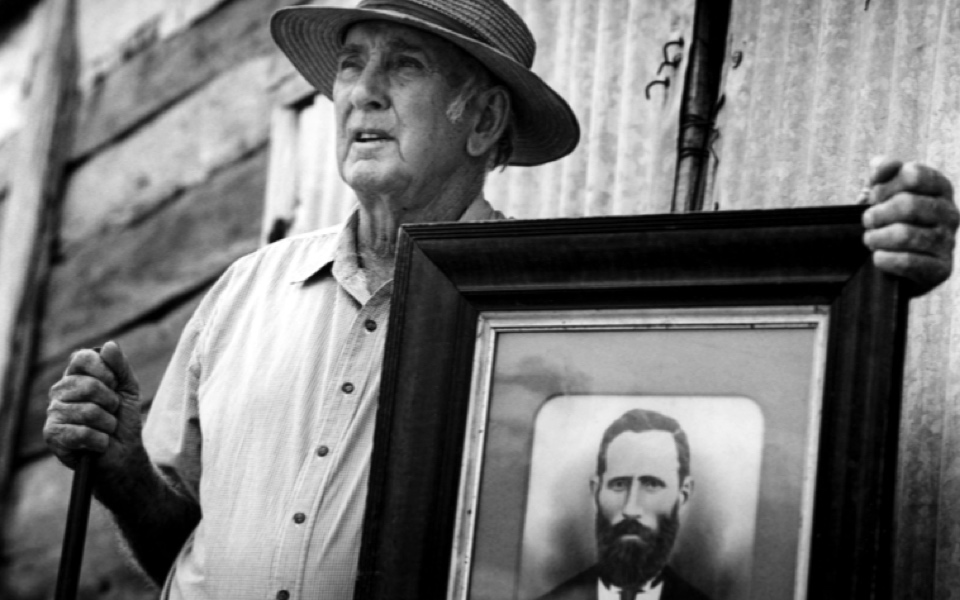

Leonard was studying for an MA. He was studying the gold rush period in Australia and he told me that he found a lot of Greek names – Greeks that came out to Australia from the 1850s in search of gold. After my father died, I seriously started focusing on documenting Greeks generally. Combining Leonard’s interest in history and my interest in photography, we traveled around the country in 1987 and 1988, which is the year that Australia celebrated its bicentenary. We met a lot of interesting people; some were searching their family roots. We found quite a few people that were connected to the early gold miners, some fourth- and fifth-generation Greek Australians. We interviewed them about their Hellenic heritage and what they knew about their forebears. We called the project “In Their Own Image” because we use personal photos of Greek Australians which I take, as well as quoting them in their own words, their voices. This project is ongoing.

Did your Hellenic roots make an impact on your interviewees?

Most of the time the Greeks would be more comfortable that I was interested in their story and that I had a Greek background. The sad thing is we were forced to do this project because Australian historians were ignoring the Greek presence. Australian historians were not interested – especially in the milk bars story… There were thousands of milk bars within Australia – the idea of the milk bar was created by a Greek, whose name was Mick Adams (Greek origin: Joachim Tavlarides). During the Great Depression, he had a café in Sydney – he closed down the café, went for a trip to visit his relatives in Greece and the United States. When he was in America, he saw a drugstore soda parlor – the concept was, if you had medicines, the soda would help the medicine go down so you’d have flavors with your soda drinks. In Greece he remembered the galaktopoleion, and the Greek communal taverna-style of eating. English dining traditionally was very stiff, upper-class and did not have that same community feeling as you had in Greece. With these ideas, he came back to Sydney and created the first modern milk bar in 1932. It was the first milk bar globally. America couldn’t use the word “bar” because it referred to alcohol. Within a few years, over 4,000 milk bars had been registered within Australia. And then the idea went to the UK and then to Europe, but the concept was actually started in Sydney by this great man.

Are there any particular stories, people or narrative styles that fascinated you more than others among the people you met for this project?

One of the stories that really had a huge impact was Maria Kosseris. She came from Kalavryta. What happened to her family, and her motivation to come to Australia “for a better life”… She talked to us about Kalavryta – we hadn’t known the history before we met her. All the men in her village, including her father, were killed by German soldiers in 1943.

It was a devastating story for this young girl to experience. She accepted a marriage proposal to get away from what was happening in Greece. She migrated in 1952 and married a man she did not know. Sometimes the stories we heard were so compelling that we visited the places that people talked about. After interviewing Maria we were intrigued and followed up by visiting Kalavryta on our next trip to Greece.

The first book we published was called “Images of Home: Mavri Xenitia.” “Mavri Xenitia” is a very strong statement. While interviewing, people would often say “mavri xenitia” to refer to how black and bleak migration can be. Many of the stories in this book were about this aspect. We looked at the deserted regions in Greece – deserted because of migration. I first visited Kythera in 1985 – which has a lot of Australian connections. I was visiting some friends and I had noticed that a whole street of houses were abandoned, they were completely deserted. Inside, there were photos on the walls of people who had left to go to Australia. There were letters telling the inhabitants about Australia, there were photo albums in cupboards. Because these personal items were left in the homes, it gave the impression that the owners were planning to return – many never did. A lot of these houses were collapsing and had been vacant since the post-war migration – some since World War I. It was like an archaeological excavation. I was on my own on that first trip. I came back to Australia and told Leonard that we should go back and see what was there in Ithaka and Kastellorizo as well. These places were where the earlier Greeks to Australia had come from. We went to these three islands to compare and of course found abandoned homes on all three islands. They left thinking they would come back. A lot of them never went back – those were really tragic stories. We wanted to talk about migration as well as the Australian settlement story.

What can you tell us about traces of solidarity in the Greek diaspora in Australia?

They say in Greece that we in Australia are more Greek than the Greeks in the sense of keeping the traditions alive… Greece has changed, it is now more European, but Greeks here in Australia are still Greeks. Many first-generation Greeks are living with what is known as “broken clock” syndrome – living in the Greece of their memory. There are many Greek organizations in Australia that belong to their regions – they have kept their regional boundaries first and foremost instead of being united as Greeks.

As part of the diaspora, have you ever felt like your artistic vision and career could have evolved differently if you had spent your childhood and adolescence in Greece?

If I had stayed in Greece, I wouldn’t have the opportunities that I have had. Migration means that the family is broken up – some people never see their parents again. Being from a small village, it really wouldn’t give me the opportunities that Australia has provided. I would have probably gotten married young, no career options, and had 10 children by now [laughing]. I think traditional village life would have been too restrictive.

Curious minds

Although Janiszewski has a Polish name, that is not the original family name. The original family name was ethnically German, and his paternal forebears were ethnic Germans living in Poland. Alexakis and Janiszewski’s collaborative project constitutes an excellent combination of two curious minds with divergent ethnicities.

Leonard Janiszewski: Effy and I are the products of post-war migration to Australia. The reason why I personally became involved in this project was political – Australia has a long history of exclusionism. It is part of British imperialist expansion – Australia was settled as a British colony in 1788. When the separate Australian colonies became a nation in 1901, the first act was known as the White Australia policy. So we were born into an Australia, where, even though it was accepting migrants from non-English speaking backgrounds, there was animosity towards our parents. When I went to university to study history, I was actually learning racist British imperialist history. That annoyed me. The Australia that you see and experience is very different from the Australia that you read about in the history books. Even today, the reality is that there is still racism in this country. There is still an attempt to exclude people based on race, language and so on. When I linked up with Effy, I was researching a particular period in Australian history – the gold rushes (1850s to 1890s). There were a lot of Greeks. The first collective Greek settlements were established during the gold rushes. Greeks were not only mining but also food catering. The food catering aspect was not the emphasis of the project – we wanted to show the diversification. What we tried to show was beyond British documentation, and what we found had contrasted and conflicted with that. We still have historians that cannot focus on the diversity of Australia’s ethnic origins. The major reason is that we cannot develop historians who can speak a language other than English and we do not have archives that have emphasis on collecting materials from non-English sources. The archives are culturally myopic. Historians only read in English from English language materials. So, as a result, what kind of a history can they develop? A British-Australian history.

Historians in this country are looking at written documents. They use the images only as adjuncts, but photographs are real documents and can give you insights that the written material cannot. For example, we recognized the Americanization process that occurred in Australia’s Greek-run cafés by looking at historical photographs that Greeks had in their collection.