Turkish interference in the 1972 election for patriarch

It’s well known that Athenagoras Spyrou was elected ecumenical patriarch in 1948 thanks largely to the influence of the United States. Then secretary of state George Marshall consulted the Greek-American businessman Spyros Skouras, and Skouras recommended Athenagoras, then archbishop of America. According to Skouras, “General Marshall, in his capacity as secretary of state, had no hesitation in sponsoring His Holiness and thanks mainly to his efforts and influence, the Holy Synod decided to elect archbishop Athenagoras as patriarch and the Turkish government agreed to his election.”

As he got older, Athenagoras tried to set the table for his succession and enlisted Skouras, who lobbied the Nixon administration. But the geopolitical situation had changed, and Nixon wouldn’t grant an audience to Skouras, who died in August 1971, failing in his mission to secure US involvement.

Athenagoras was not alone in thinking about succession. In 1970, the Prefecture of Istanbul issued a directive on the selection of future ecumenical patriarchs. Under these rules, the Holy Synod of Constantinople would draw up a list of candidates within a certain time, then submit it to the governor of Istanbul. The governor would remove any names deemed objectionable by the Turkish authorities and return it to the Holy Synod for election.

The day Athenagoras died – July 7, 1972 – US vice president Spiro Agnew (himself a Greek American, though not an Orthodox Christian) met with archbishop Iakovos, the head of the Greek Archdiocese of America. Iakovos wanted to become the next patriarch but was at odds with the Turkish government and, no longer a Turkish citizen, technically ineligible. Iakovos begged Agnew to attend Athenagoras’ funeral in Istanbul, but Agnew declined, instead speculating that Nixon could appoint Iakovos to lead an ecumenical delegation to the funeral.

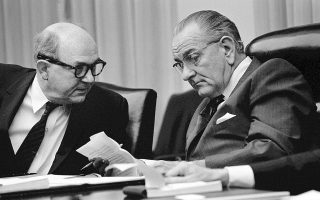

After speaking with Iakovos, Agnew called secretary of state Henry Kissinger. We have a transcript of that call, which has been declassified. Kissinger was uneasy about appointing Iakovos to represent the United States at the funeral: “I have to make sure that this doesn’t take sides in succession.” Agnew pushed a bit, cautioning against “being too considerate of the Turkish bishops of no advantage to us whatsoever.” Kissinger countered, “I don’t give a damn about the Turkish bishops. I give a damn about the Turkish government.”

Two days later, a Turkish official called the US State Department, adamantly rejecting Iakovos’ entry into Turkey. According to a State Department report, the question of the archbishop entering Turkey “had been reviewed at highest level of GOT [Government of Turkey]; that Iakovos would not be permitted to enter Turkey; that Iakovos was an ex-Turkish citizen who had lost citizenship and who had worked against best interests of Turkey; that his presence in Turkey during delicate period following death of patriarch was considered particularly undesirable.” Kissinger added in another call with Agnew, “a Greek patriarch in Istanbul is not just a religious figure and that, apparently as far as I understand, they don’t want to have Yakovos [sic] as their patriarch.”

On July 13, Harold Saunders of the National Security Council sent a memo to Kissinger: “The desirability of our continued non-involvement seems clear.” Saunders then described the Turkish rules for the election, adding, “This process has been going on since Athenagoras’ funeral on Tuesday. We understand that the Holy Synod submitted a list (which includes Meliton [of Chalcedon], the compromise candidate) to the Istanbul governor after the Turks insisted they do so within 72 hours. The Turkish press says the Turks, after they edit the list, may be asking that the election take place within the next 72 hours. Finally, the Turk government has indicated publicly that if the election procedures are not followed it may have to appoint a new patriarch though it has told our embassy in Ankara that it wishes to avoid this.”

This enraged Iakovos. He sent a telegram to George H.W. Bush, then US ambassador to the United Nations, asking him to make an “immediate personal expression of protest to the United Nations in reaction to the unprecedented Turkish government interference in the election of the ecumenical patriarch.” In fact, in addition to 1948, the Turkish government meddled extensively in the internal affairs of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the 1920s, and there are countless examples from the Ottoman period.

The US Embassy in Ankara told Saunders that the Turks had promised not to be “heavy-handed in editing the list of candidates.” This was a lie: The Turkish government vetoed both Iakovos and Meliton of Chalcedon. According to a later account by Ecumenical Patriarch Vartholomaios, in the 1972 election the Turks vetoed no fewer than four candidates. (Other sources put the number of vetoed candidates as high as five.)

Saunders’ memo to Kissinger ends depressingly: “The fact is that the Turks for years have been harassing the Patriarchate, half wishing it would decide to withdraw. Given the Orthodox desire to stay in Istanbul, the Greeks at least seem to have resigned themselves to living with the situation. We are not likely to be able to change it.”

The election of the next ecumenical patriarch took place at the Phanar on July 16, 1972. The final three candidates were metropolitans Dimitrios of Imbros and Tenedos, Nicholas of Anneon and Gabriel of Colonia. The Holy Synod members voted via secret ballot, placing slips of paper into a silver urn that sat in front of the patriarchal throne. Dimitrios won the election with 12 of the 15 votes.

The new patriarch, Dimitrios was a dark-horse candidate, a humble and heretofore obscure teacher and pastor. Reporting on the election, the Associated Press wrote, “Informants said Dimitrios would be guided in most matters by Meliton, who is a strong advocate of Orthodox unity. Dimitrios is essentially a pastoral cleric with little experience in matters of state, they said.”

Patriarch Dimitrios remained on the throne for nearly two decades, until his death in 1991. The election of his successor, Patriarch Vartholomaios, went much more smoothly, with the Istanbul governor not vetoing any candidates.

Matthew Namee is a lawyer and editor of www.orthodoxhistory.com