Why don’t we celebrate July 24, 1974?

The transition from a dictatorship to a democracy on July 24, 1974 is the epitome of what we call a “historic day,” yet it has never been celebrated as a national anniversary. Even though the events of that day are always remembered in the press and in announcements from political parties, its actual celebration was quickly demoted to a social occasion of little importance. Nowadays it concerns only a few dozen guests invited to the customary reception hosted by the Greek president and the journalists covering that event. It does not concern society as a whole, which is mostly ignorant of the event and of the celebration.

The first anniversary on July 24, 1975 was a much different occasion. It was declared a public holiday for the civil service and was marked with every possible formality in Athens and the rest of Greece. It was, however, also overshadowed by protest rallies organized by the two most dynamic social movements of the time, that of the students and that of construction workers. The rally by striking builders on July 23 was huge but police prevented the protesters from marching, leading to extensive clashes. The protesters erected barricades and fought street battles with the police, which flooded the city center with tear gas. Official government announcements the following day spoke of “different elements, either belonging to various extreme-left organizations or individuals suspected of activities during the dictatorship too.”

How the anniversary was marked changed radically after the tumult of 1975, with an announcement appearing in the press on June 21, 1976, stating that it would be celebrated with a reception in the garden of the Presidential Mansion. No rallies were permitted and for the public sector it was business as usual. A protocol was established that year which remains more or less the same to this day. So why wasn’t the date proclaimed a national anniversary?

National anniversaries are not always established for strictly historical reasons, meaning that whether an event is pivotal or historical may not be of primary importance, hence not every historical event is commemorated or celebrated. It takes a string of factors for an event to be established as a national anniversary. The political leadership selects those past events whose commemoration, along with the corresponding narrative about the past, acts in a way that unites rather than divides the public body and strengthens the national identity. An external foe is usually the main factor, as is the case with the anniversaries of March 25 and October 28. This factor is absent from July 24. There is an external enemy at play in the overall story (Turkey) but it was not defeated, and the nation was anything but united. What’s more, celebrating the restoration of democracy would have put the country’s political forces and society in a very awkward position, because the anniversary would not be linked to some national success or victory, but to a national tragedy – the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Greece could not be seen to celebrate an occasion that in Cyprus was so deeply traumatic. Last, and equally important, is the fact that a pivotal factor in all national anniversaries is absent from the events of July 24, and that is the people.

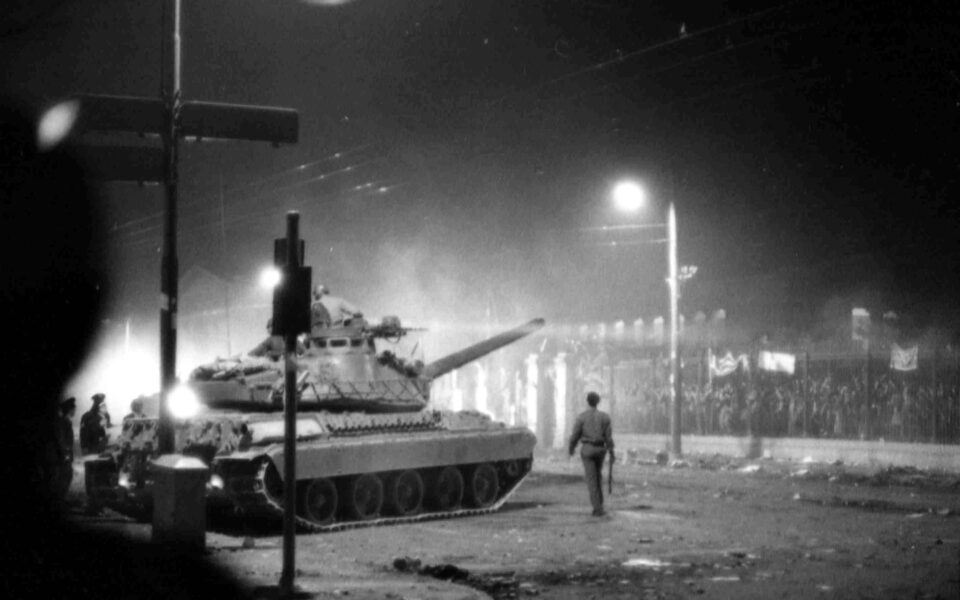

Compared with July 24, the November 17 Athens Polytechnic Uprising had everything needed to become a historical landmark in the political landscape of the Metapolitefsi, as the long process of restoring democracy after the dictatorship is known. The narrative which emerged was from the very first moment clear, conveyable and incredibly symbolic. The students’ resistance to the military regime dovetailed with the national “tradition” of resisting oppression, but what November 17 has, mainly, is a collective subject, as every anniversary ought to have in order to convey an attractive image of the collective self. As on May 25, when the collective subject is the rebelling nation, and on October 28, when the people and the military fought to defend the nation, so on November 17, we had the students and the people who embraced their uprising. The violent and bloody crackdown on the movement by the military regime created new heroes who could be inducted into the pantheon of freedom fighters, on the one hand, and, on the other, united Greek society against a common rival: the enemies of democracy. Last but not least, let us not forget that this is an anniversary which was established by the grassroots (student associations, political youth parties, ordinary citizens etc). Even though the government did not recognize or participate in celebrations until 1981, tens of thousands of citizens flocked every year to the events organized on the historic campus of the Athens Polytechnic and took part in the customary march to the US Embassy.

The official commemoration of November 17 was instituted by Law 543/1985 in order to pay homage not just to the student uprising but also more generally as a tribute to the resistance against the military regime. It is worth noting that this piece of legislation stemmed from Law 1285/1982 on the recognition of the National Resistance in World War II, thus associating the anti-dictatorship movement with the Resistance and giving the narrative a sense of continuity.

For many young men and women in the Metapolitefsi who had not lived through the events of 1973, the memory of the uprising felt as poignant as a personal experience; it became, in short, their own heroic past, a past that they had not experienced themselves, but chose to adopt as their own. In every anniversary of the Polytechnic Uprising, thousands of young people all over Greece have found a common political and emotional pretext to address the issues that concern them in the present. The slogan “marching for our generation’s Polytechnic [uprising]” is indicative of this trend, but also of a sense of duty to fight for what you believe in that was cultivated by the events of 1973. The Athens Polytechnic Uprising acquired such symbolic force in the collective memory that people started to believe the junta fell as a result of the student rebellion and that resistance to the regime was on a mass scale.

In conclusion, anniversaries are not really associated with the historical weight of certain events that took place in the past as they are with whether those events can be inducted into and serve a pre-existing narrative about the collective self. This narrative, as a rule, showcases and confirms the “enduring” virtues of the nation, of the populace, which is invited to celebrate and participate in the events and ceremonies held on that day. Despite its historical significance, July 24 could not serve this purpose because the collective subject did not play a part in the developments that took place in the summer of 1974 and, therefore, could not be a part of any celebrations. November 17, in contrast, restored the image of the collective self, as the 1973 student uprising had all the hallmarks needed to be regarded as the founding legend of the Third Greek Republic. And this is why it continues to be celebrated and to resonate so strongly with the Greek people 50 years later.

Polymeris Voglis is a history professor at the University of Thessaly. Eleni Paschaloudi is a historian.