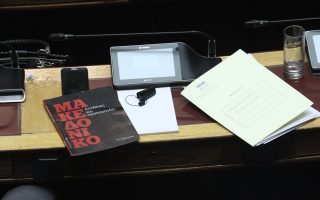

FAQs: The Greece-FYROM name deal

The ratification of the Prespes agreement signals a new chapter for both Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), and also raises a series of questions regarding the future of the two countries. Here, we address some of these questions and attempt to provide some answers.

1. How does the agreement relate to FYROM’s NATO bid?

The Prespes agreement will go into full effect once FYROM becomes a member. Following the ratification of the deal in the Greek Parliament on January 25, the Balkan country will be invited by NATO, within the next few days, to sign an accession protocol as “Republic of North Macedonia.” However, its accession will have to be approved by all 29 parliaments of NATO’s member-states, including Greece’s. This could take more than a year, judging by Montenegro’s accession in 2017.

2. Can Russia scupper the deal by vetoing it at the UN Security Council?

Under the terms of the agreement, the Security Council and the UN secretary-general are only required to acknowledge its entry into force. There is therefore no way for Russia to challenge the agreement.

3. Could the agreement be annulled in Greece by a future government under New Democracy, which has expressed its opposition to the deal?

A process similar to that which prevented FYROM from joining NATO in 2008 (by threatening a veto) cannot be repeated. The Greek Parliament’s ratification of the Prespes agreement lifted the only obstacle to the country’s accession in 2008 – its constitutional name. New Democracy leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis has said that Greece reserves the right to veto FYROM’s accession to the European Union. However, under Article 2, Paragraph 1 of the agreement, Greece agrees “not to object to the application by or the membership of [North Macedonia]… in international, multilateral and regional organizations and institutions of which [Greece] is a member.” Furthermore, Article 20, Paragraph 9 makes it clear that the provisions of the agreement “are irrevocable.”

Greece can of course set terms concerning the implementation of the 35 chapters of the accession process, but the crux of the matter is that the agreement prevents Greece from exercising a veto. Any violation of this could result in the country being isolated by the international community and condemned by the International Court of Justice.

As far as FYROM’s EU accession is concerned, France and the Netherlands have raised objections to setting a date for the start of talks. Nevertheless, the process is expected to commence in June or December and to take several years. This means that the accession of “North Macedonia” to the EU will take place after the next Greek government’s term has expired.

4. How does Greece benefit from the agreement?

Supporters of the accord stress the fact that it settles an issue that has absorbed precious diplomatic capital for 27 years. Greece is also credited with making a decisive contribution to bolstering the West’s role in the Balkans, as FYROM’s accession to Western institutions is seen stemming Russia’s (and Turkey’s) influence in the region, despite the fact that this is exercised through religious and cultural networks that operate independently of political developments. Greece’s greatest gain, perhaps, is that it achieved certain fundamental demands, such as forcing the neighboring country to change its constitutional name to a composite name with a geographical qualifier, something that has been the Greek national policy line since 2008. Greece also achieved additional changes to FYROM’s constitution that remove any irredentist elements. It achieved a clear differentiation between the history of ancient Macedonia and the history of FYROM – even though some experts stress that efforts to usurp the history of ancient Macedonia were simply a strategy of the former administration under Nikola Gruevski and had already been abandoned by Skopje.

Furthermore, while the agreement acknowledges the language spoken in FYROM as “Macedonian” – seen as a concession by Athens, for which, in exchange, it clinched a composite name to be used erga omnes (meaning both domestically and internationally) – Greece “won” the explanation in Article 7, Paragraph 4 that this language belongs to the group of South Slavic languages.

5. Does the agreement open up new economic opportunities for Greece?

The complete normalization of relations with Skopje will certainly open up new opportunities for Greece from an economic standpoint, and not just in FYROM, but across the Balkans. The region of Greek Macedonia and the whole of northern Greece are expected to benefit quite significantly as Thessaloniki is expected to become a focal point of numerous initiatives.

6. What has Greece lost as a result of the agreement?

Even though Greece set a composite name with a geographical qualifier as its national policy line in 2008, a large part of public opinion still remains committed to the position adopted by the Council of Political Leaders in 1992, which opposed any name that contained the term “Macedonia.” Therefore, even though the national policy line has shifted, the majority of citizens regard FYROM’s renaming as “North Macedonia” as a defeat rather than a victory for Greece.

The second concession pointed out by naysayers is the acceptance of the name “Macedonian” for the Slavic dialect (or language) spoken in the neighboring country, as well as the adoption of the ambiguous English term “nationality” (which is used in the agreement), which can be taken to mean both “ethnicity” and “citizenship.” This ambiguity is seen as tantamount to Greece accepting that the people of FYROM are of “Macedonian” ethnicity. The recognition of a “Macedonian” nationality, which has also irked the Balkan’s state’s ethnic Albanian community, is admittedly a point that could be seen as fueling irredentism.

Furthermore, the belief that the agreement was imposed on Greece by foreign forces has also taken a toll. It also resulted in the collapse of the SYRIZA-Independent Greeks coalition, leaving the country to be governed by a government which doesn’t have a parliamentary majority.

7. Why are the nationality and language clauses regarded as such major defeats?

matter how clearly the historical legacy of ancient Macedonia – which is Greek – is differentiated from the history of the geographical area north of Greek Macedonia, the nationality and the language defined by the agreement appear to allow the Slav-speaking population of FYROM to regard itself as a part of a Macedonian nation. In this sense, critics argue, the agreement officially establishes, by recognizing a “Macedonian” language and a “Macedonian” nationality, that Macedonia is not just Greek – it is multiethnic. Despite claims that Greece accepted the “Macedonian” language in 1977 at the United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names, the fact is that the only thing recognized at the time was the “Macedonian-Cyrillic alphabet.” After all, if the “Macedonian” language had indeed been recognized in 1977, it would not have been such a crucial point of discord from 1992 to the present.

8. Can you really fight irredentism?

Optimists point out that the expected expansion of Greek investment in the neighboring country will weaken irredentist tendencies. Meanwhile, skeptics warn that Greek recognition of the country’s “Macedonian” identity marks a milestone in the propagation of irredentism and the further consolidation of Slav-Macedonian national ideology – the ideological construction of “Macedonianism” – which came into being in the late 19th century. According to this ideology, Aegean Macedonia is under Greek occupation while Pirin Macedonia is under Bulgarian occupation.

9. Could the existence of a “North Macedonia” pose a threat to Greece?

Historical time cannot be reduced to natural time. Greece will not face any threat in the coming years; in fact it will grow stronger as stability solidifies in the Balkans. However, FYROM’s upgrade into “North Macedonia” and the recognition of a “Macedonian identity” may in historical terms amount to sowing the seeds for something greater. The neighboring state will evolve into the autonomous facilitator of Macedonian identity. In a future geopolitical development 30, 40 or 50 years from now, the great powers might back the creation of a single, multiethnic federal Macedonian state – inside or outside the European Union – that would drive a wedge in the Balkans. Such geopolitical calculations lie behind Bulgaria’s reservations over the Prespes agreement.