A French-Greek alliance in Suez

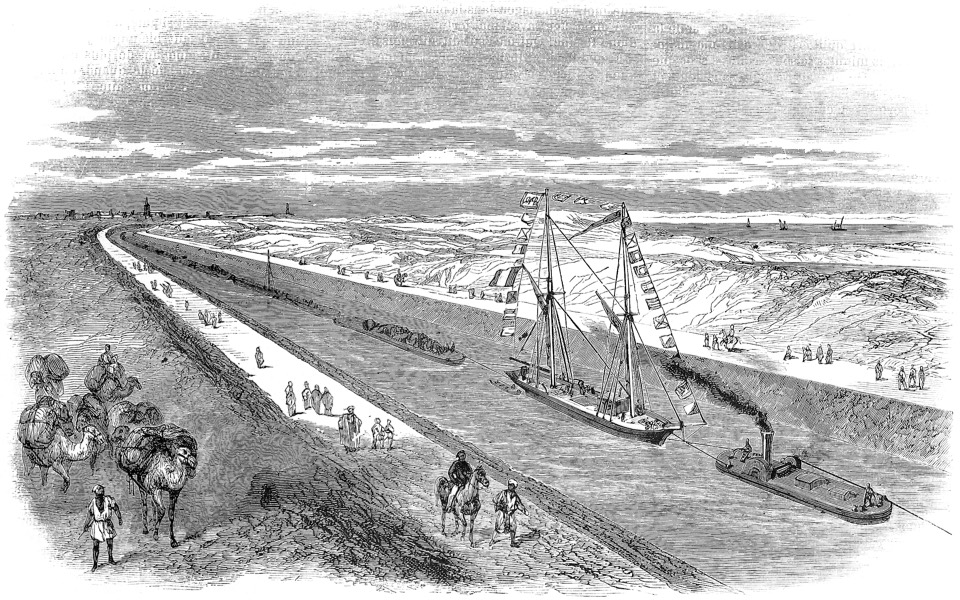

Phileas Fogg could not have made his trip around the world in 80 days, in the 1872 novel of the same name by Jules Verne, if the Suez Canal had not opened three years before it was published. Building the canal in just 10 years (1859-69) was a huge achievement for the engineers of the Compagnie Universelle du canal maritime de Suez (Suez Canal Company), founded for this purpose by French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps. But the building could not have happened without the thousands of Egyptian and foreign workers that toiled on the construction site in a project that recalled the pharaonic works of long ago in its size and ambition. Of the 7,000 foreign workers, 5,000 were Greek. And of the latter, 3,000 came from a small island in the Dodecanese, Kassos. Their contribution to the project was so important that, after it was finished, de Lesseps wanted to express his gratitude to the Kassiotes in a concrete manner. They asked him to name the new port built from scratch at the Mediterranean end of the canal Nea Kassos. But he (or, rather, an international committee made up of representatives of six countries) had already given it the name of the viceroy of Egypt, Mohamed Sa’id. So Port Sa’id it was.

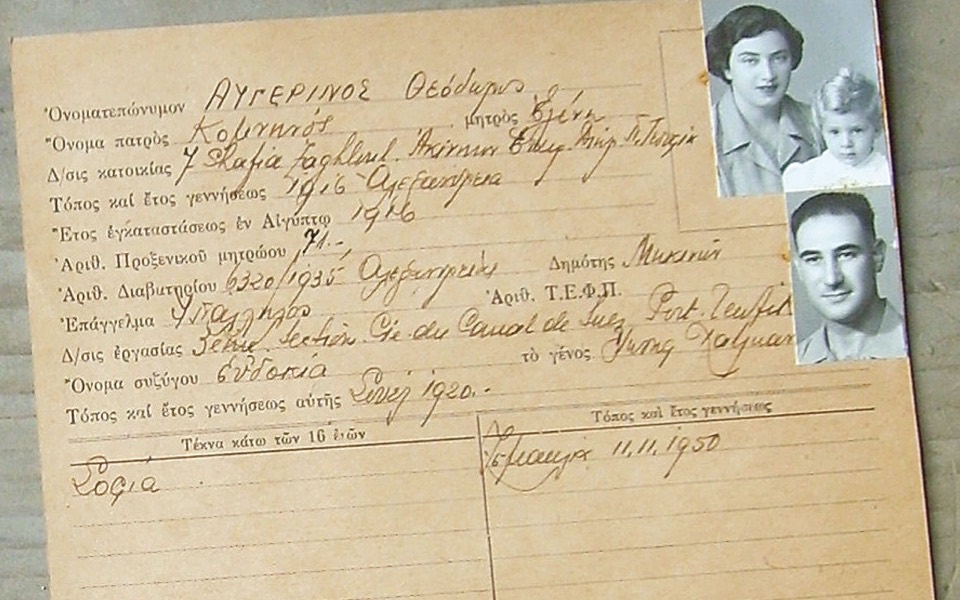

An employee’s card for one of the Greek workers in the Suez Canal Company. [Greek Community of Suez Archive]

The story of the naming reminds us of the contribution of Kassiotes, and Greeks in general, to the building of the canal and the bond of trust they formed with the ingenious Frenchman. The Greeks had arrived in Egypt to work for the famous company, the pride of French engineering and symbol of France’s economic and political penetration in the region. Both during the construction of the canal and later, during its functioning, the company was the largest private employer in the Eastern Mediterranean. For a century, until the nationalization of the French company in 1956, the Greeks who had stayed in the cities near the canal after 1869 made up the majority of its foreign employees.

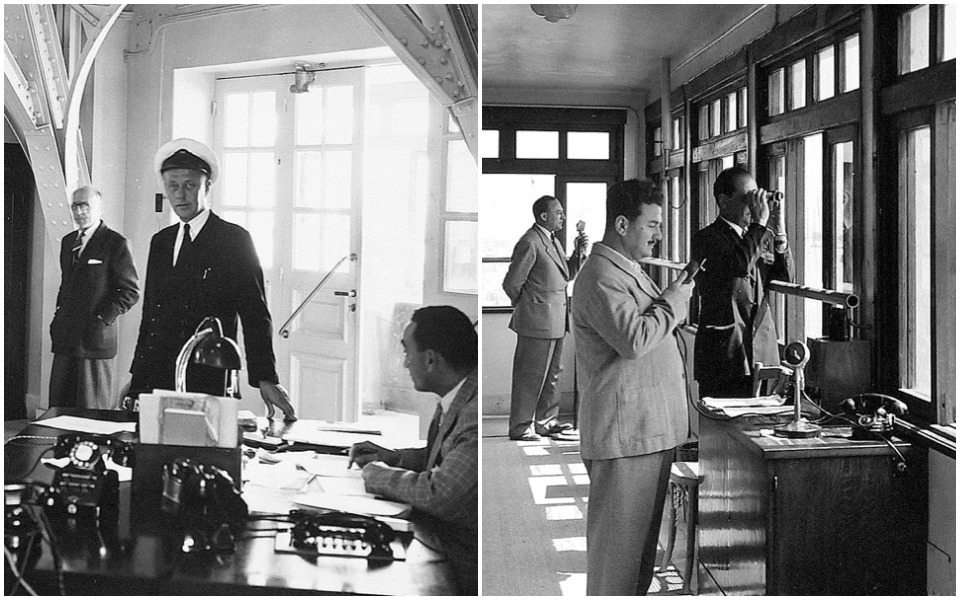

Within the company, Greeks occupied crucial mid- and lower-level jobs (navigation pilots, foremen, administration staff as well as sailors, dredger captains and unskilled laborers). The fact that Greeks did not identify with a colonial power competitive with France or hostile to Egypt, such as Britain, allowed them to be in close contact both with the French, mostly upper management, and the Egyptians, who had lower positions. Language proficiency helped, since many Greeks spoke both French and Arabic.

Even though we refer to them as a single group, the Greeks in fact were a highly diverse group because of their professional positions, different incomes and places of origin. Each one’s position often determined their relationship with the company. Some enjoyed good positions and wages, allowing them to take family summer vacations at French spas and educate their children at French universities.

Greeks also played a role in the labor movement within the company from the end of the 1870s to the 1920s, while also taking part in the anti-colonial movement of the 1950s. Most of the company’s Greek employees stayed in Egypt after its nationalization in 1956. Navigation pilots, especially, contributed decisively to Gamal Abdel Nasser’s diplomatic victory during the Suez crisis.

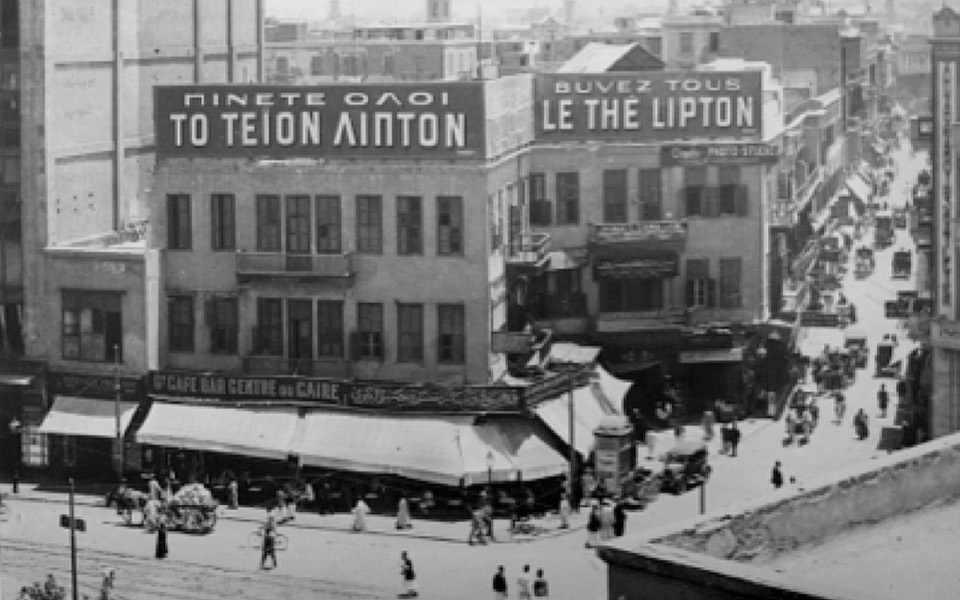

In any case, the French presence in cities along the canal during the company’s operation under French control was so pronounced that it made relations with the Greeks inevitable. The latter could be treated at French hospitals, educated at the company’s technical schools or the Francophone catholic schools, and take part in the July 14 festivities organized by the company.

The coexistence of French and Greeks in Egypt through the Suez Canal Company was decisive in developing employment and business relations between the two on Egyptian soil. Thanks to the dynamic unleashed by the construction of the canal, the wider region underwent a political and economic transformation during the second half of the 19th century that made it part of the global capitalist system through the implantation of large multinationals. French businesses provided significant opportunities, not only for employment but also for investments and collaboration with Egypt’s considerable Greek-owned capital in several sectors, such as banking, which grew very fast at the end of the 19th century.

Banks and networks

In 1880, Konstantinos Salvagos, Antonios Rallis and Amvrosios Synadinos were members of the founding board of directors of French bank Credit Foncier Egyptien, Egypt’s second largest company after the canal operator. At about the same time, Banque Generale d’Egypte was founded, specializing in providing credit for cotton, sugar and wheat exports. As a successor of the banking house Sinadino, Ralli et Cie, the new bank attracted big local businesses and considerable capital from French banks such as Paribas, Societe Generale and Banque d’Escompte. Theodoros Rallis was the first chairman of the board, while where the representatives of Sinadino, Ralli et Cie on the board lived reflects the extent of Greek financial networks: Konstantinos Synadinos lived in Alexandria, Amvrosios Synadinos in Cairo and Theodore Rodokanakis in Paris.

Greek expatriate economic networks were also behind the Societe Marseillaise de Credit in Egypt; Leonidas Zarifis and Stephanos Zafiropoulos, Greek bankers and traders from Constantinople who had lived in Marseille since 1845, were the bank’s liaisons with Egypt. Land Bank and Union Fonciere, founded in 1905, was a result of the collaboration of the Societe Marseillaise de Credit with prominent Greeks of Alexandria. The first board contained an equal number of representatives from Alexandria and Marseille: The chairman was Amvrosios Zervoudakis and Mikes Salvagos, Georgios Zervoudakis and Pericles Zarifis were members, while Jules Charles-Roux, representing the French bank, was also vice chairman of the Suez Canal Company.

Until the middle of the 20th century, the interconnections between French and Greek businesses and Greek labor networks in Egypt remained considerable. But with the transition from colonial powers to nation-states, these connections were gradually transferred to Greece. Dimitris Charitatos, the manager of an Alexandrian company, with roots in Kassos, arrived in Greece in 1961. Soon, he became head of Pechiney’s newly built aluminum plant and helped attract many Greeks, especially Greeks with roots in Kassos, who left Egypt around the same time, seeking employment in Greece. Using networks based on local lineage and already familiar with French companies, the Greeks of Egypt soon became a significant percentage of employees at Aluminium of Greece’s plant.

The Greeks of Egypt and the French of the Suez Canal Company and Pechiney were the two constituent elements of French-Greek economic relations on both coasts of the Mediterranean. A relationship without winners or losers. Around the Mediterranean and beyond, Greek expatriates, from unskilled laborers to tycoons, cooperated, at many different levels, with French engineers, businessmen and diplomats, in a relationship mostly complementary for both sides’ economic and other interests.

Angelos Dalachanis is a research historian at France’s Centre Nationale de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS).