Defenseless against the masters of the fake

The recent dismantling of fraud rings producing forged artworks has highlighted the institutional gap for authenticity certification in Greece

He harbored no illusions. It was only the low price of the artwork – a mere 1,500 euros, when its value should have been multiple times higher – that made him suspect it was of “doubtful origin.” The painting was attributed to a Greek artist and was supposed to have been created during the period when the artist resided in France. On its reverse side, there was a handwritten certificate of authenticity dated 1989, bearing the signature and seal of a well-known art historian, who, however, was no longer alive to verify its authenticity. In a move reminiscent of a gambler, the collector decided to purchase it.

“Usually, you know, but you take the risk,” he tells Kathimerini under the condition of anonymity. “It’s difficult and time-consuming to verify authenticity. I might have been suspicious; logic would suggest it’s fake, but there’s also a chance it’s not.”

The approach one takes in the world of art acquisitions can vary based on motivation, aesthetic criteria and financial capability. This particular collector says that passion guides him. “I try to find opportunities. I don’t buy from auction houses or galleries, but directly from individuals or antique shops. This increases the risk of ending up with a forgery,” he asserts. Paradoxical as it may seem, he chooses this approach even when he suspects that the seller may be attempting to deceive him.

Two fraud rings

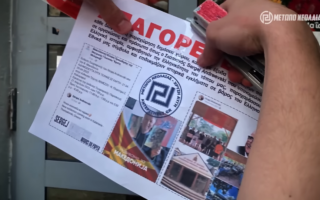

Over the past three months, law enforcement authorities have dismantled two fraud rings engaged in the long-term sale of counterfeit artworks. Just this week an 80-year-old man was arrested for art forgery and fraud. In the most recent case of a forgery ring, one of the narratives concocted by the forgers to circulate their paintings involved the name of an associate of gallery owner Alexander Iolas. Supposedly, the associate had sold them a sketchbook with drawings by Kandinsky and a painting by Picasso. Kathimerini contacted him directly, and he categorically denied any such transaction. “I have never had those artworks in my possession,” he stated.

However, these two cases concerning art forgery rings bring to the fore an unresolved issue in Greece: the institutional gap when a private individual seeks to authenticate a work of art. Kathimerini spoke with collectors, dealers and art historians. Many either refused to comment, fearing misinterpretation, or chose to remain anonymous. The issue of forgeries, despite concerning the art world for decades, remains delicate. Rarely does a buyer publicly admit to being deceived.

Marilena Cassimatis, an art historian and former curator at the National Gallery, recalls that for years works were brought to the gallery to determine authenticity, but written evaluation certificates were not signed to avoid potential legal complications. The experts at the gallery are only called upon, based on legislation, to certify a work if requested by law enforcement, prosecutorial or judicial authorities. According to the gallery, in contrast to other countries like France, Greece has no established role of an appraiser who undergoes relevant training, is supervised by the Justice Ministry and resolves such matters for private individuals.

Cassimatis recalls hearing “tales of unbelievable fantasy” from individuals claiming to be art owners trying to construct a plausible collection history. In one such case, a person asserted that the imprint left on their wall, where the painting was hanging, was proof of authenticity as it showed it had been there “for generations.” Another time, a woman presented a drawing, after claiming to be the former domestic helper of Konstantinos Parthenis. She insisted that the artist had given her the work as a Christmas gift and it thus had significant monetary value. However, the drawing turned out to be a widely circulated replica. When the art historian informed her, the woman threatened her. She may have felt that her dream collapsed,” says Cassimatis.

Half are suspicious

“There is no institution in Greece, no official body, like in other countries, that certifies authenticity,” an art dealer with extensive experience in the field tells Kathimerini. “I believe that if a buyer acquires a work at auction or from a reputable dealer considered trustworthy, it reduces the chances of being deceived and increases the likelihood, if they believe they were deceived, of getting their money back.” As he points out, half of the artworks that arrived in his office were returned either because they were blatant forgeries or due to doubts over their authenticity.

The issue of forgeries, despite concerning the art world for decades, remains delicate. Rarely does a buyer publicly admit to being deceived

“In many cases, the work speaks for itself. We browse the literature, and if we find its history published, there is some assurance,” he says. The scrutiny becomes even more thorough for works that appear out of nowhere, often accompanied by the narrative that an elderly lady had owned them and her relatives discovered them after her death.

Manolis Platsidakis, a collector and a specialist in the works of Yiannis Spyropoulos, explains that, following the advice of an art historian, another crucial link in the art certification chain is a scientifically trained conservator with a well-equipped laboratory. They can examine the age of the paint, technique, canvas and even determine if the signature was added at a later stage. However, this alone doesn’t seem sufficient. “They can certify if a work is fake, but they cannot specify who held the brush,” says Platsidakis.

There is yet another crucial link: a researcher – not necessarily a collector – who has devoted their life to studying a specific artist. They delve not only into the painter’s technique but also know who purchased their works, who the collectors were, where and through whom they were circulated, where they were exhibited, under what title and their dimensions. Another significant source of information on authenticity can be the artist’s family.

An odyssey

Twenty years ago, Platsidakis attempted to research a painting from the early 19th century, a self-portrait by a French artist. During a professional trip to Marseille, the artist’s hometown, he located two experts in his work, a gallery owner and a lawyer, along with two volumes showcasing his creations. The specialists confirmed the authenticity, as well as the aesthetic and artistic value of the painting. However, it was not included in the critical catalogue of the painter’s works. The painting’s collection history was missing.

He tried to put together the pieces on his own. He found that the artwork in question had been sold in 1932 in Paris for 15,000 French francs. This information was inscribed in pencil on a copy of the auction catalogue, which he discovered in the archives of the Getty Research Institute in the US.

Later, he discovered that in 1939, the same artwork appeared in a renowned gallery exhibition in Amsterdam and was purchased by a Dutch couple who held onto it until their death in 2003. He gathered all relevant information from the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD). Currently, the painting is part of a private collection in Athens, accompanied by related documents and a clipping from a 1939 Dutch newspaper, referencing that year’s exhibition along with a photograph.

As Platsidakis observes, in contemporary times, such research journeys can become even more challenging, as international auction houses often do not disclose a complete collection history, citing confidentiality obligations toward the seller.

‘Baking’ forgeries

In one of the art forgery cases exposed last November in Greece, one of the involved individuals is alleged to have skillfully crafted paintings after in-depth studies on the artists to whom the works were later attributed. According to the police, this person sourced materials from antique shops in Monastiraki, a flea market neighborhood in downtown Athens, and placed the artworks in ovens, attempting to impart aging characteristics.

Systematic examination of an artist’s work is a fundamental practice for a skilled forger. German art forger Wolfgang Beltracchi employed this method for decades, creating paintings attributed to, among others, Max Ernst and Fernand Leger. He, along with his wife, managed to deceive international auction houses and experts by presenting forged works as authentic often from a secret collection. In 2011, he confessed and was sentenced to six years in prison. In 2022, psychoanalyst and author Jeannette Fischer published a book based on conversations with Beltracchi and his wife.

Her interest was to understand how, over time, this particular forger, an undeniably skilled artist, eradicated his own signature, to mimic the technique of others for decades. She clarified that she approached the couple psychoanalytically and not to pass legal or ethical judgments. “His career in forgery didn’t arise because he failed as a painter or feared how his art would be accepted. Being an artist was just not enough for him,” the author said. “He forged the signature of a painter and crafted paintings that those artists could have created.”

In Athens, collector Platsidakis expresses concern about the collateral consequences of art forgery cases. “The genuine artistic production of the artist is distorted, and consequently, cultural heritage is damaged,” he says. “The risk is that the eye, especially of young collectors, becomes so accustomed to the fake that when someone tries to sell an authentic painting, they have to prove that it’s not an white elephant.”