Warnings of Cyprus invasion went unheeded

Ex-head of Greek Central Intelligence Service in Kyrenia recounts events leading up to Turkish landing

It was not a matter of instinct, he did not suddenly feel that danger was imminent. Alexandros Simeoforidis was going by the facts – and they were loud and clear. As head of the Greek Central Intelligence Service (KYP) contingent in Kyrenia, Cyprus, he was tasked with intercepting and deciphering Turkish conversations and observing the movements of military units in Alexandretta and Mersin. For at least three months in 1974, he had observed unusual and escalating activity. He had recorded in intelligence signals intensive landing exercises, holiday leave revocations, requests for supplies of military materials and massive transfers of ammunition, and he had informed his superiors of the possibility of a Turkish invasion. His warnings were timely, but they were not heeded.

“I sent so much information! And what happened to it? It was wasted! Shouldn’t it have been used so that we could have had a different outcome?” The retired colonel still wonders, even today at the age of 87. “We were so well-informed nothing could move without us knowing about it. And it was all for naught; as if we were oblivious. And then the Turks came, ‘unexpectedly.’ I felt betrayed,” he says.

These days Simeoforidis is in Raches, in the region of Fthiotida, where he usually spends his summers. A local villager, also a retired officer, had instructions to wait for us outside the Church of Agios Haralambos to show us through the narrow streets to his neighbor’s doorstep. “You’re in for a treat! It’s an incredible story,” he tells us before we wave him off. A compact man with a rapid gait, Simeoforidis invites us into his living room. His story has not changed and he recounts it without pauses, recalling dates and names of military units. Even though almost half a century has passed since the Turkish invasion, every year, whenever the July 20 approaches, that turbulent period comes rushing back. “I’m back in Cyprus, mentally,” he says.

‘I sent so much information! And what happened to it? It was wasted! Shouldn’t it have been used so that we could have had a different outcome?’

Simeoforidis was born in Pentavryso in Kastoria and graduated from the Military Academy. After sitting exams in 1960, he did a year of Turkish language classes at the armed forces’ foreign language school. In 1963, KYP applied to the Army General Staff for three unmarried, Turkish-speaking officers to join its ranks. He was among them and was sent to a post in Didymoteicho in northeastern Greece in May 1964. Four years later he was sent to Kyrenia, Cyprus.

There, he kept tabs on the movements of, among others, Turkey’s 6th Army Corps in Adana and the 39th Division based in Alexandretta. Every September this division carried out a landing exercise from Mersin to Antioch, in which one of its three regiments took part on a rotating basis. In April 1974, however, all three regiments carried out successive landing exercises within the space of a few days. “It was unusual,” he notes.

There were other worrying signs. In June that year, all leave permits in the Turkish military were suddenly revoked. Simeoforidis says that a major from the 49th regiment was seen in Alexandretta, tens of kilometers away from his post. “The general got wind of it and asked for his head on a platter.” He remembers another Turkish officer who was mapping the Pentemili coast, where the landing was to take place, swimming with a mask. The head of the KYP contingent was feeding all this information to his superiors. The recipients of his signals were the National Guard General Staff, the Greek Force in Cyprus and the Greek Embassy, while copies of his reports were also sent to the KYP’s headquarters in Athens. “Our people knew that the Turkish military had been on alert since April,” he says.

After the coup

Developments accelerated after the coup of July 15, 1974. Two days later an emergency meeting of Turkish senior officers was held in Mersin, where 16 landing craft were stationed. This was followed by the “descent of the myriads,” as Simeoforidis describes it. The conscription of 5,000 men was ordered to fill gaps in the units – something uncommon in peacetime – while the commander of the engineer battalion was ordered to uproot as many trees as possible on the coast of Mersin in order to prepare the area for the arrival of the troops.

There was a burst of preparations on the other side. Reconnaissance flights were made over Cyprus, while ammunition depots of various calibers were gradually emptied and transported to the coast in commandeered trucks. Simeoforidis recalls a Turkish signal stating that all vehicles had to be filled with fuel and soldiers had to wear long-sleeved uniforms because they would be crawling. Under normal circumstances, he would send his superiors one or two intelligence signals within a 24-hour period. In that turbulent time, though, he remembers sending 17 to 18 a day. “I received no response, no instructions,” he says. “It was as if they already knew everything and didn’t need any additional information.” He watched the course the Turkish convoy was charting towards Cyprus and remained optimistic until the last moment. He thought there would be a reaction. “Those of us in the contingent were rubbing our hands with glee. The Turks are in for a surprise, and they will remember it for years to come, we told each other,” he recalls.

It was barely dawn on July 20, 1974, when he spotted the Turkish fleet off Kyrenia. He was struck by the fact that the crew members were on deck, looking relaxed, with no special security measures, as if they were on their way for an inspection after a drill. On the Pentemili coast, no organized precautionary defensive measures had been taken. He would later call the Turkish military operation a “disembarkation,” not a landing.

Aflame

With the Turkish fleet moored across the way, the head of the KYP task force in Kyrenia received orders from Athens to move as close to the landing area as possible and to keep the operations room in Greece informed on all the developments. He was expecting the arrival of six Phantom fighter jets and two submarines that would require exact coordinates to strike against Turkish targets. They never arrived. Without a way of immediately contacting headquarters, he attached a spool of wire to the telephone wires, climbed up a three-story construction site nearby and began transmitting details on the vehicles that were being unloaded by the Erkin landing craft. The wire was not long enough to reach the roof of the building, so he had a colleague on the ground floor to hold the telephone.

“I stood there using my binoculars, or just using my own eyes; it is impossible to describe, as eloquent as you may be, the spectacle, that atmosphere. There wasn’t a centimeter of land that was not aflame, or that was not being bombarded. It was hell! When someone is in that kind of atmosphere, he does not consider the risk of dying. It is like being drunk,” said Alexandros Simeoforidis, describing the events of that day to an investigative committee in the Greek Parliament on the “Cyprus File,” in October 1986.

And as he was transmitting the detail frontline to Athens, he was asked to calculate where the water line of the Erkin was, both then and before the landings began. The water line, or to put it differently loading line, is the maximum allowed displacement for a ship. “I began cursing gods and demons,” says Simeoforidis. It was a technical question that seemed out of place at such a critical moment of the invasion. “What where they interested in, where the water line was or where the tanks were?” he says.

Simeoforidis ran into a wall of skepticism at various other stages. He says he had seen 72 Turkish helicopters flying overhead, and the response from Athens was that he did not know how to count and that Turkey had no more than 30 or 35 helicopters.

He remembers a Turkish tank running over a soldier and another flattening a car. Any resistance during those hours was rudimentary, “isolated acts of bravery.” As the Turkish tanks closed in, he was forced to flee, though he was captured and imprisoned for 17 days.

Captivity

Simeoforidis had made provisions, having predicted the possibility that events will turn against the defenders, and had burnt documents at the local KYP offices, as well as destroying a machine and disposing of two others down a well. He had to eliminate everything that could be used to reveal his activities. If he was captured with all this equipment, he was certain he would be condemned to death.

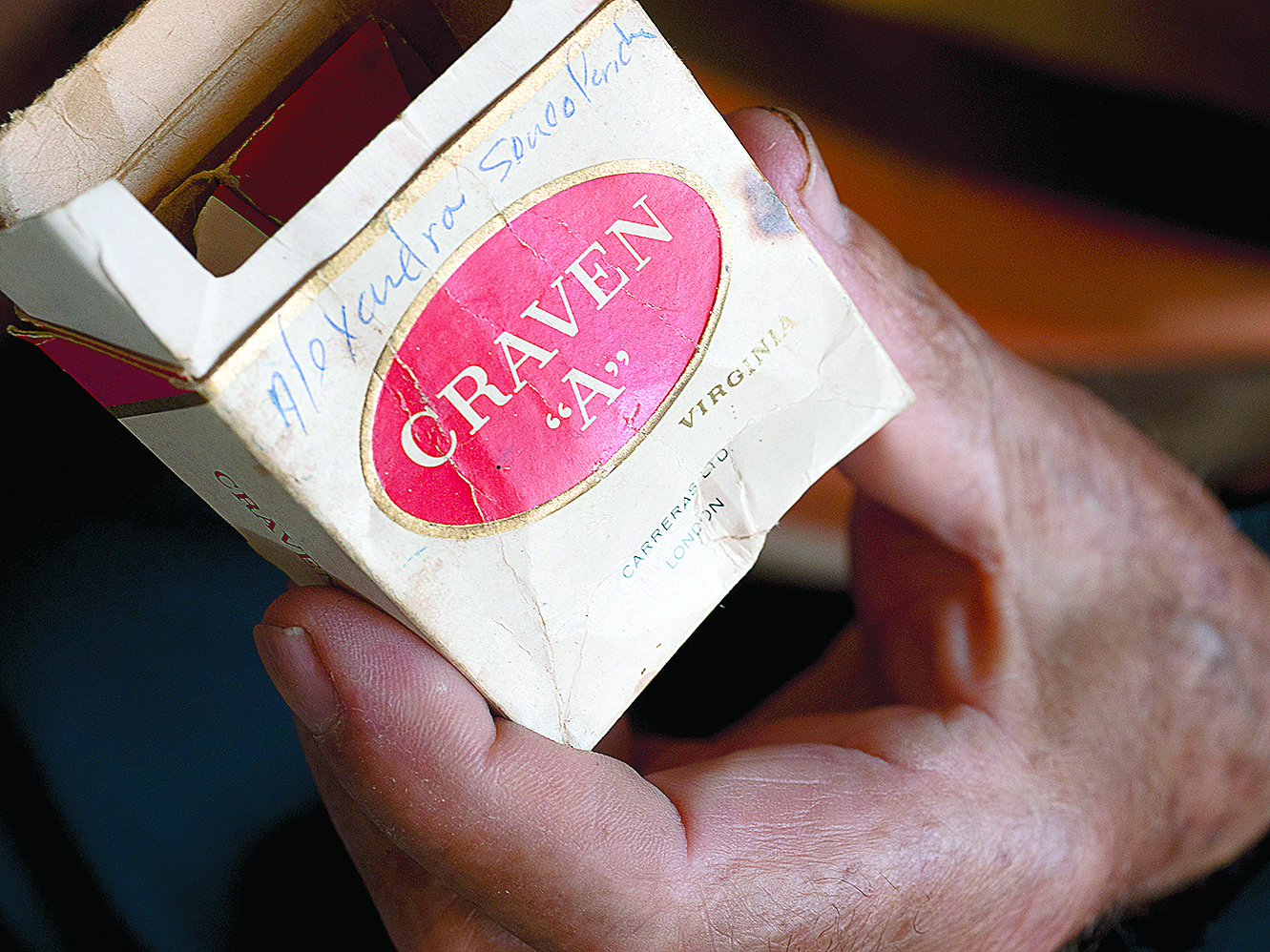

He remembers the interrogations, the dark cell and the scant meals. A wafer-thin slice of bread and three olives were breakfast, a chicken wing cut into three pieces and a bit of pasta was lunch. And that was it. He lost 9 kilograms in two weeks. He thought he was going to be executed, until one day he was unexpectedly released, following a prisoner exchange. “Can you imagine being free after being convinced of your impending execution? How can a body withstand that?” he says. To this day he keeps the crumpled pack of British cigarettes, Craven A, that he had on him when he was captured and was returned to him shortly before his release.

He continued serving in Cyprus until 1978 and was later moved to the Greek consulate in Istanbul for four years, serving as a consular port official and assistant trade attache. He retired in 1985. He believes things could have been different if the extensive intelligence he had compiled had been put to use. “Everything I sent was self-evident, they did not need an analyst to see what was coming next,” he says.