‘Calling Palestinians terrorists has to stop’

Kathimerini presents excerpts from a taped conversation by then prime minister on a crucial 1982 European Council meeting

It was June 29, 1982 and Andreas Papandreou had just returned from a fraught European Economic Community summit. The Greek prime minister gave his family a detailed account of what was said during the talks with his European counterparts with regard to the war that was raging in the Middle East at the time. Here, Kathimerini reveals extracts of that conversation, which was captured on tape, for the first time.

Papandreou had been prime minister for eight months after PASOK’s victory in the October 18, 1981, elections when he was invited to attend the European Council meeting in Brussels on June 28 and 29, 1982. He went home to his family in the northern Athens suburb of Kastri as soon as he returned, where he recounted the events of the meeting to his wife Margaret, their sons George and Nikos, and his son-in-law Theodoros Katsanevas, in a conversation that was recorded on tape.

The entire conversation was dedicated to the European summit and the crisis that had erupted in the Middle East after Israel invaded Lebanon on June 6, 1982, sparking a war that the Israeli government had dubbed Operation Peace for Galilee and later became known as the First Lebanon War. The tape, an important piece of historical documentation owned by the Andreas Papandreou Foundation, has been transcribed by Kathimerini and the excerpts presented here demonstrate how little has changed in the Middle East in the past 40 years. It also offers a rare glimpse into the private life of the founder of the socialist PASOK party and three-time prime minister. The setting is a warm summer’s night in the garden of the family’s home in Kastri.

It was less than a year since PASOK had been voted into power in October 1981, and Greece had not departed from the European Economic Community (as the European Union was then known, with just 10 member-states), despite the socialists’ pre-election proclamations. As confirmed by people who knew the founder of PASOK personally, Papandreou had never intended to make such a thing happen. “If people actually believed we’d go ahead with it, they never would have given us such a large majority,” he is alleged to have said. Indeed, the son of the “Old Man of Democracy” Georgios Papandreou, the former Berkeley University economics professor and anti-dictatorship leader, seemed to enjoy the opportunity to meet with the “big players” and have his opinions heard. He did not hold many of them in particularly high regard either. As he is said to have confided in certain people in his close circle, he thought many of the top decision-makers on the international stage at the time as mediocre in terms of intellect and education. However, he would also admit that “they represent their country’s institutional order and clout, and that makes them important.”

Before moving on to Papandreou’s conversation with his family, though, let us describe the context in which the European Council meeting took place.

On June 3, 1982, a man called Hussein Ghassan Said shot the Israeli ambassador to London at the time, Shlomo Argov, as he left a banquet at the Dorchester Hotel. Argov survived the shooting but was in a coma for three months and spent the rest of his life struggling with serious disabilities until his death in 2003. Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) denied any involvement with the assassination attempt, which was found to have been the work of an organization created by Abu Nidal, who had left the PLO’s dominant faction, Arafat’s Fatah, in 1974 and went on to establish how own militant group, which has been responsible for multiple attacks in Europe and elsewhere. It has been said that Nidal’s real aim was to provoke the Israeli invasion of Lebanon so as to defeat Arafat.

Israel’s attack on Lebanon began on Sunday, June 6, 1982. On Tuesday, June 8, the Syrian air force invaded Israel’s airspace, losing six MiGs in three air battles. Iran weighed in saying that it was prepared to go to war with Israel, which went on to surround Syrian and Palestinian forces in West Beirut and, on June 9, to down at least 82 Syrian jets and 29 missile systems in the Bekaa Valley supplied to Syria by the Soviet Union. These events, among others, led to the European summit on June 28 and 29.

“I believe the summit marked a major turning point… it was catalytic in terms of Europe’s political orientation and, secondly, with regard to my own position,” Papandreou told his family on the night of June 29, though not before making a comment on the food he had in Brussels. “We arrived at noon on Monday and went directly to the palace where the king treated us to lunch. The food in Belgium is very mediocre. Everywhere you go, it’s mediocre, even impressively bad. Even the king’s food was poor. At least the wine was decent.”

‘It is unconscionable for a politically responsible Europe to accuse the Palestinians of being terrorists. They are fighting to reclaim their lost homeland’

‘My friend Mitterrand’

After the “mediocre” lunch at the palace, Papandreou attended the summit, where he spoke in favor of the Palestinians. “The meeting began at 3… and Lebanon-Palestine was the first order of business. It took us until 6, 6.30 or thereabouts. Three, three and a half hours. As you can imagine, I was very energetic and spoke knowledgeably and passionately on the subject, telling them that this business of calling Palestinians terrorists had to stop, once and for all.”

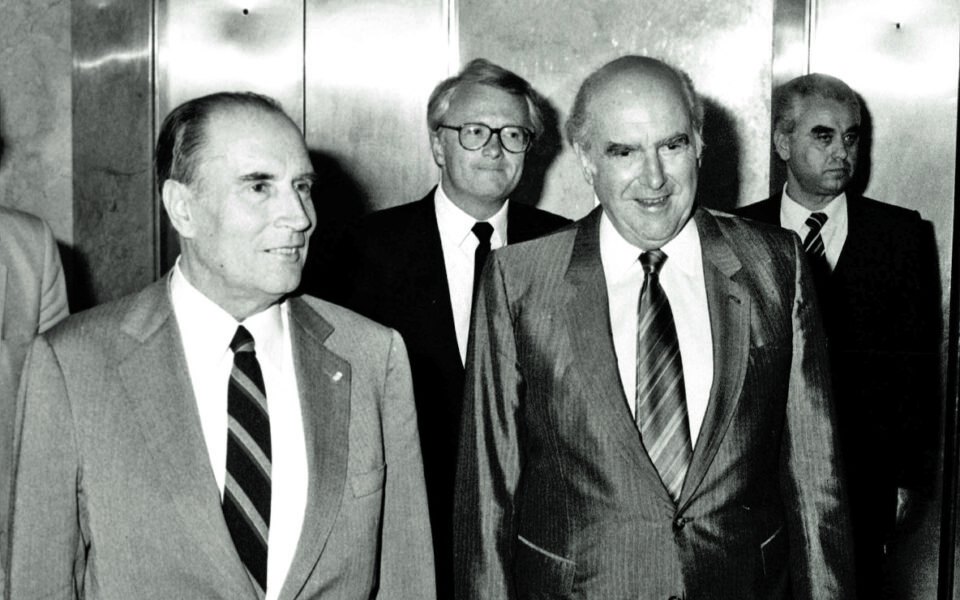

Addressing his “friend” French President Francois Mitterrand, Papandreou spoke of the shift in relations with Algeria, saying that they were regarded as terrorists when fighting for their independence from France and had gone on to become its closest friends and partners.

“I cannot – I said – but remind you that there are 200,000 refugees from Cyprus. The Palestinians have been driven from their homeland for 35 years. They have a right to do what they need to do. It is unconscionable for a politically responsible Europe to accuse the Palestinians of being terrorists. The Palestinians are fighting to reclaim their lost homeland. I said a lot on the subject,” Papandreou recounted.

In another part of the tape, he described a conversation with Germany’s chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, who asked the Greek prime minister whether he had any solid information to suggest that Israelis had America’s backing for their invasion of Lebanon. Papandreou’s response, he told his family, was: “What kind of information do I need, Mister Schmidt, all of Israel’s weapons are American, all they’d need to do is tell [Israeli prime minister Menachem] Begin to sit tight. Who are we kidding, asking what America’s role in Israel is?”

He went on to talk about the debate about European weapons sales to Israel. “What made a very big impression on me was that a proposal was put forward to introduce a ban on selling weapons to Israel,” he said, recounting objections to a clause outlining such a ban because it would be tantamount to an admission that certain member-states were indeed selling arms to Israel. That is when the minister of foreign affairs for the UK apparently stood up and admitted that his country, and Italy also, had, in fact, been selling arms to the Israelis, but would agree to stop. “That’s when I said that under these circumstances, it must be ensured that we [Europe] don’t do so again,” Papandreou said of his reaction to the British minister’s admission. “Revolution. Mitterrand agreed with me. He listened. Mitterrand is now with me; a complete shift.”

Papandreou appeared satisfied by the stance toward him, particularly from Mitterrand and Schmidt. “Mitterrand… supports me not just in this but in other matters too… And Schmidt, for his part, feels very comfortable with me,” the Greek prime minister told his family.

Arafat in Faliro

That summer ended with a victory for the Israelis, but the epilogue for the Palestinians was written in Athens. Under siege from Israeli forces in Lebanon, Arafat realized that the war was lost and in late August decided to move the PLO’s headquarters to Tunis, while ordering the PLO militants to disband and leave Lebanon. Information had leaked, however, that Arafat would not be safe on this journey, as there were plans afoot to have him kidnapped. That is when the Palestinian leader reached out to his old friend Andreas Papandreou. That friendship dated back to the Greek military dictatorship of 1967-74, when Arafat offered support for the Panhellenic Liberation Movement founded by Papandreou, including military training in the Middle East for young Greek resistance fighters. Papandreou honored this friendship in 1982, offering cover and safe passage for Arafat, who sailed on a Greek ship to Faliro in southern Athens on August 30 and was met there by the Greek prime minister.

Other European leaders did not comment on the move, with the exception of the Italian president, Alessandro Pertini, who expressed his support for the initiative. Rallies in favor of the Palestinians were also organized in Athens during Arafat’s visit, while the two leaders held a joint press conference at the Hotel Grande Bretagne, before Arafat left for Tunis.

By the mid-1980s, Papandreou had evolved into a leader with some influence over the course of events in Europe, while relations with the United States also warmed and he visited the White House in 1994 as a guest of Bill Clinton. His friendship with Arafat, nonetheless, remained unwavering. Indeed, the Palestinian leader became a fixture at all PASOK’s congresses in 1984, 1994, 1996 and even 2001, when the president of the socialist party was Costas Simitis. Andreas Papandreou had made Arafat a part of his party’s history and anyone who attended the fourth congress in 2001 at the Olympic Stadium Arena will remember the hero’s welcome he received from 6,000 congregants, as though they were cheering for Andreas himself.