The notion of ‘Britishness’ and the Parthenon Sculptures

How the ancient Greek artifacts became an element of English nationalism from the very first

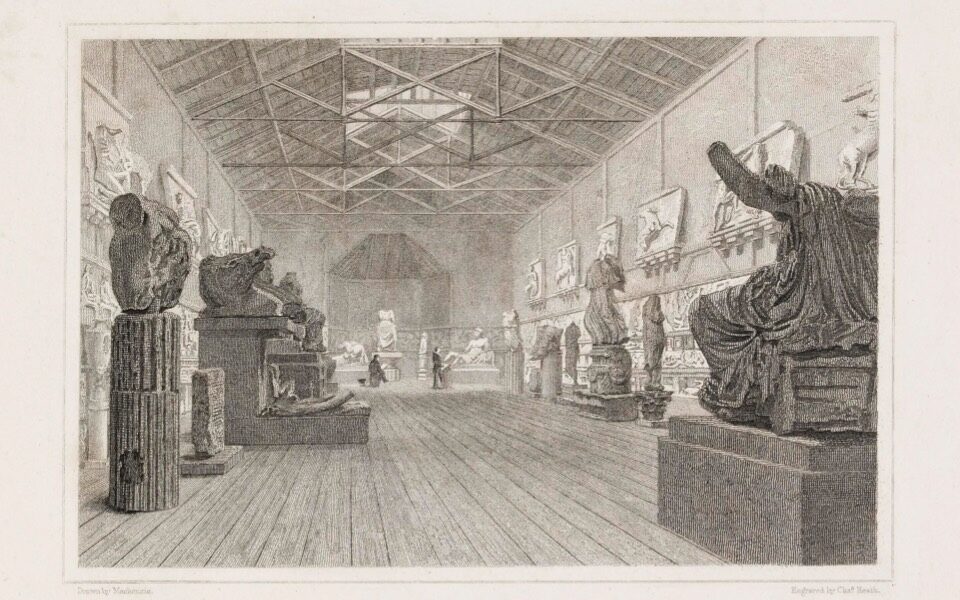

It was no ordinary breakfast gathering. In June 1808, Sir Anthony Carlisle, a surgeon and leading member of London’s elite, had prepared a surprise for his all-male, art-loving toffish guests, taking them to a room where boxing champion Bob Gregson stood posed like an exhibit. Ten days later, the same group was invited to a shed used by Lord Elgin and where again they could admire the pugilist’s form, this time juxtaposed beside the Parthenon Sculptures.

A few weeks later, that same shed was used to host a boxing match between top British pugilists set against the marble sculptures, an event that was described as the “perfect match between nature and art.”

These vignettes appear in the diary of Joseph Farington, a regular visitor to the makeshift exhibition space created by Lord Elgin, which he described as being too cold in the winter and too hot in the summer.

Symbolic value

Fiona Greenland, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Virginia, has studied Farington’s diary, along with British Museum records and more than 1,000 newspaper publications from the early 19th century, to explore how London’s elite, but also people outside this circle, gradually came to regard the Parthenon Marbles as symbols of “Britishness.”

“Ι was really puzzled by the question how something made in Greece by Greek people was absorbed into British national identity. How did that happen? Usually we are taught that nationalism focuses on home-ground creations and it takes a lot of pride, it really tries to separate out non-national people and creation,” Greenland tells Kathimerini.

She believes that the juxtaposition of naked or half-naked athletes – boxing was incredibly popular among the upper classes at the time – beside the ancient Greek sculptures was not unwitting or merely a way of advertising the marbles.

“To me it’s very clear there was a very intimate physical comparison happening to show that the British athletes could compete with the best of the Greek sculptured men. I think Elgin and his associates were very conscious of trying to absorb the sculptures into the British mentality,” Greenland notes.

‘Within Britain those who might wish to support restitution are faced with accusations of political weakness and disloyalty’

As she writes in a paper on the subject, Elgin appears to have been making a concerted effort to convince his audience that Britain was the natural setting for the looted sculptures. “If the naked pugilists looked just like the mounted Greek warriors in the frieze, then Britons could mount a claim to embody the legacy of ancient Athens,” she argues.

We do not know how many people in the UK still believe that the Parthenon Marbles are a part of the British national identity and heritage, nor how decisive this could be in shaping their stance and position in the ongoing controversy. Last March, however, the influential, London-based conservative think tank Policy Exchange published a 63-page analysis on the Parthenon Sculptures, written by Sir Noel Malcolm. The journalist, historian and academic argues against the marbles’ return to Greece, saying that “the claim that Greek identity is essentially harmed by their absence from Greece is greatly exaggerated.” He also claims that “over more than 200 years they have become part of Britain’s cultural heritage.”

Speaking to Kathimerini, Greenland notes a shift in public opinion in recent years, with polls showing that the majority of Britons are in favor of returning the sculptures to Greece. She also, however, points to the reactions of Britons who are opposed.

“If you look at the rhetoric against restitution in the UK you will see people using the phrase ‘losing its marbles’ or ‘losing the marbles.’ So for some people restitution is a weakness, a political weakness. It signals capitulation, perhaps lack of loyalty to the British nation or the British Museum. Within Britain those who might wish to support restitution are faced with accusations of political weakness and disloyalty and this might be very difficult to overcome particularly for people seeking elective office,” she says.

Appropriation

Richard Hingley, professor emeritus of Roman archaeology at the University of Durham, notes that approaches to antiquity that can be traced several centuries back often constitute an effort to appropriate the past of others. He says that something similar happened in Britain with Rome.

“Classical Greece and classical Rome were so much admired in Britain that people tried to find a connection. Ιn the late 19th to the early 20th century people were using that classical past very directly to justify what the British were doing in their empire,” he tells Kathimerini.

However, he adds, “I think a lot of people in Britain think that the British Empire is over and we live in a different world.”

‘White marble, white race’

In her 2012 paper “The Parthenon Marbles as Icons of Nationalism in 19th century Britain,” Greenland notes that Elgin and his network of acquaintances among the higher echelons of British society launched an informal public relations campaign to promote the Parthenon Sculptures, before these ended up at the British Museum. They wrote letters to newspapers lauding their aesthetic qualities, while politicians warned of the risk of these masterpieces of classical art ending up in the hands of foreign collectors.

As she notes, a supranational narrative was formed over time which suggested that the marbles belong to everyone, while at the same time arguing that ancient Athens was a lost utopia that had no bearing on modern Greece. According to this line of thinking, endowing these antiquities with an universal character was a way of justifying their continued removal from Greece.

Another element that may have contributed to this approach, Greenfield argues, may have been the color of the marbles. Even though they were not white in ancient times, the white patina they acquired over time, the monochromy, “makes it easier to project our own selves onto it.”

“White marble can be read as white people – British white, as Elgin and his circle saw it,” she argues.