Bloody 1989 revolution casts a long shadow in Romania

BRASOV, Romania – After attending a ceremony in May commemorating her dead son and others killed in Romania’s 1989 revolution, a despondent mother – driven to despair by more than three decades of fruitless efforts to find out who killed her 12-year-old boy – made a final plea for justice.

She left the park where the ceremony had been held – and where her son was buried – in Brasov, in Romania’s Transylvania region, and drove into the mountains outside the city. In the shade of a beech tree, she doused her body with gasoline and set herself alight.

The woman, Ileana Negru, died soon after an ambulance arrived.

“Today I end the humiliation, though it is costing me my life,” a handwritten message found by her body said. “The revolution was ours and in no way belongs to the Communists who stole it.”

Of all of the revolutions that swept across East and Central Europe in 1989, Romania’s was the most violent and muddled. Afterward, many of those who had served the country’s deposed dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu – executed on Christmas Day 1989 – not only stayed in power, but also enjoyed expansive opportunities for enrichment for themselves and their families.

The despair that pushed Negru, a 66-year-old widow, to suicide flowed from forces existing across Eastern Europe – unresolved traumas left by the epochal changes of three decades ago, when communism gave way to capitalism, and dictatorship to promises of democracy.

Catalin Giurcanu, a friend of Negru’s, recalled how as a “romantic 16-year-old” he had joined street protests against Ceausescu in December 1989 and how he lost his father, who had come to look for him, in a hail of gunfire from still unidentified gunmen, almost certainly members of Romania’s dreaded Communist-era secret police agency, the Securitate.

When Ceausescu was three days later put before a firing squad with his wife, Elena, after a show trial, Giurcanu celebrated what he believed was a new dawn.

“Everyone thought the Communist era was over and everything would start anew,” he said. “But there was no new start. There was no real rupture. And we are still living with the consequences.”

Even though some state institutions are working to track the killings of protesters in 1989, and to provide support for the families of victims, many servants of the Ceausescu regime, particularly former Securitate officers and a vast network of informers, still cast a long shadow.

In July, Romania’s highest court acquitted two Securitate officers over the 1985 death of a dissident, Gheorghe Ursu, who died from beatings while in their custody. A panel of three judges ignored testimony from former dissidents who described being tortured, and sided with witnesses from the security services who claimed, against all evidence, that detainees were never subjected to violence.

Andrei Ursu, the dissident’s son and an author of two books on the 1989 revolution, said the judgment fit a rewriting of history long promoted by former Securitate agents – and helped explain why Negru had so much trouble getting justice for her dead son, Florin.

Negru, in a 2006 interview for a Romanian documentary, recounted how she last saw Florin alive on December 21, 1989, when, fearful that he might join snowballing protests against Ceausescu, she left him and his younger sister in the care of their grandmother before going to work.

When shooting erupted in Brasov, she was thankful “that the kids were safe at my mother’s.”

Florin was not. He had gone into the streets and disappeared.

A day later, Negru found him: He was lying on a winter jacket at a military hospital piled with corpses. He was, she recalled, “wide-eyed, smiling,” but ice-cold. When she reached down to hug him, she said, “my hands entered his back.” His spine had been blown away.

“It was empty,” she said. “It was a hole, a hole.”

The nature of Florin’s wounds, said Ursu, who has studied the case as part of his research, indicated that the boy had been hit by an expanding dumdum bullet, to which only the Securitate had access in Romania.

But when Negru appealed to military prosecutors in Brasov in the 1990s to investigate, she was told “that my son was a terrorist,” according to an account she later submitted as part of efforts to press the authorities for a full investigation.

She was blocked by a narrative promoted by the Securitate that the 1989 revolution had come under threat from “terrorists” working for foreign powers and had been saved by patriots in the security apparatus.

“There were terrorists. They existed,” Ursu said. “But they were Securitate officers.” When he put forward that view in a book last year and presented documentary and other evidence, he was fired from his job as research director at the state-funded Institute of the Romanian Revolution of December 1989.

“Killers have been turned into patriotic defenders of the nation and victims into terrorists,” he said by telephone from Chicago, where he now lives.

For Mihai Dodu, who heads a government department responsible for helping anti-Communist protesters from 1989 and their families, a “mix of bureaucratic stupidity and deliberate sabotage” had prevented Negru and many others from finding out how their loved ones were killed.

Nearly 1,300 protesters died in December 1989, and more than 3,000 were wounded. Nobody has been held responsible for a single specific case of murder.

Dodu, whose father was killed in 1989, met Negru in Bucharest, the capital, a few days before her death and was helping her with a tangle of bureaucratic problems. She was, he recalled, “in a very delicate emotional state.”

“I identified with her,” Dodu said, “I saw my mother in her eyes. There was a terrible, yawning sadness,” he added. “She told me I could have been her son.”

Like Negru’s son, Dodu’s father was killed by a type of bullet used exclusively by the Securitate on the night of December 22, 1989. Ceausescu, fearing for his life after the military went over to the side of protesters, had just fled Bucharest. His successors, hijacking the popular revolution on the street, presided over a period of wild bloodshed blamed on “terrorists” as they consolidated their grip on power.

Romania’s new leader after Ceausescu’s capture and execution was Ion Iliescu, a Communist apparatchik who served two terms as Romania’s first post-Communist president. He gave immunity to Securitate agents and for years blocked the release of their archives.

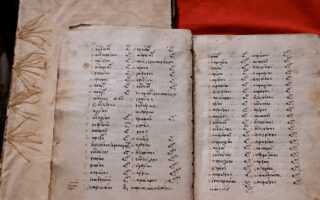

Even after files began to dribble out in the late 1990s, said Germina Nagat, a member of the National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives, a state body that collects documents and exposes past crimes, Iliescu ensured “impunity for all former Securitate officers – he protected them.”

“This is a cancer that has spread into the bones of the system,” she said.

The vast archive, though far from complete because many documents were destroyed or put beyond the reach of archivists, has exposed a host of prominent Romanians as Communist-era Securitate informers. These include Dan Voiculescu, a hugely influential media mogul, politician and one of Romania’s richest men.

Iliescu left office in 2004 and, now 93, is in ill health, but his allies are still sprinkled throughout the system, particularly in the judiciary and the security apparatus.

Sorin Boaca, a Brasov resident who was interrogated in August 1989 over his anti-Communist views and participated in the protest where Florin Negru was killed, recalled how the security agent who had questioned him became an influential municipal official in the 1990s and, after his death, was declared a martyr of the revolution.

“Everything got turned upside down,” Boaca said. “The system collapsed but its servants survived and thrived.”

Gen Iulian Vlad, the national chief of the Securitate in 1989, was arrested after Ceausescu’s execution and initially charged with complicity in genocide. But, after the charges were reduced to “favoring genocide,” he served only four years in jail. None of his underlings spent time in jail for killing protesters.

Elena Vlase, a friend of Negru’s whose 19-year-old son, Nicolae, was killed in Brasov in December 1989, has also spent decades battling for the truth. The two women talked in May at the ceremony in the park for the victims of 1989 and agreed to meet the next morning.

“I waited and waited, but she never showed up,” Vlase said. When she learned later that Negru had taken her life, Vlase “was totally shocked,” but vowed to keep going on her own quest. “I can never accept that these criminals don’t pay,” she said.

Negru, denied a burial in the main section of one of Brasov’s cemeteries because the Orthodox Church forbids suicide, is buried in the last row of graves next to a corn field. It is reserved for sinners.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.