Turkey’s crocodile tears over Alexandroupoli

The past couple of months have seen a steady escalation in the rhetoric emanating from Turkey against the increased presence of American forces in different parts of Greece, following the recent defense agreement signed between Athens and Washington, with Ankara contemptuously accusing Greece of turning into a US military base. With 38 American installations in its own territory – 15 of which are military bases – Turkey should have little to say on the subject.

Ankara’s feigned concern for Greece – which, it says, is ceding its sovereignty by allowing a greater American military presence – appears to be focused on Alexandroupoli in the north. Turkish media and politicians assign varying interpretations to the concentration of US forces in that part of northern Greece, but most are framed in the context of Greek-Turkish tensions and include the outrageous claim that Greek and American forces are gathering there with the aim of launching an attack on Turkey.

We all recognize such observations for the provocative inanities that they are. They are obviously directed at a domestic audience and aimed at activating anti-Western, anti-American, anti-Greek and nationalist impulses and justifying the Turkish government’s revisionist and aggressive policies. The situation is certainly being analyzed behind closed doors by the competent experts so succinctly, so as to reveal the anxiety of the Turkish president, who has said, among other anti-Greek rants, that the US made a “mistake” in its choice between the two neighbors, while also accusing Washington of having the wrong stance in the “position it has adopted along with Greece over the Aegean.”

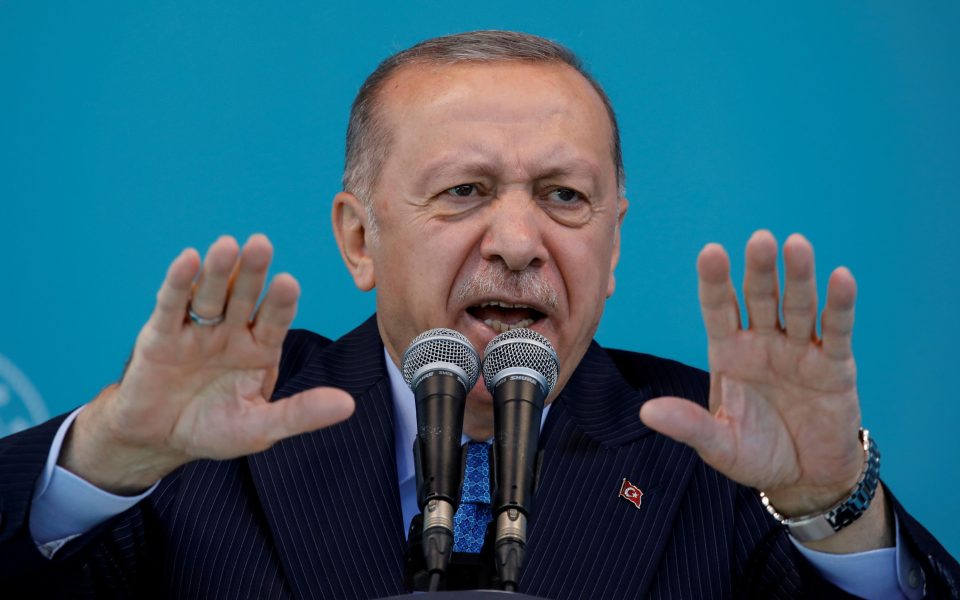

What Recep Tayyip Erdogan is trying to express, in other words, is his dismay at the US having chosen Greece over Turkey and his puzzlement about what brought about this change. He and his analysts have obviously understood by now that the strategy for the security architecture of Southern and Southeastern Europe is changing slowly but surely – and that this is definitely not to Turkey’s benefit.

The massive importance of the Bosporus Strait and efforts to stem Russian expansion into “warmer waters” in the early 20th century resulted in Turkey being assigned control of the strait and Greece controlling egress from the passage. Thanks to three successive lines of defense in the Aegean (Limnos-Lesvos; Evia-Cyclades-Ikaria-Samos; and Kythira-Crete-Karpathos-Rhodes), Greece can intercept anyone who slips past Turkey through the strait. Later, during the Cold War, Greece and Turkey were part of NATO’s Southern Flank (from Spain to Turkey), its barrier against the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact states.

Mr Erdogan’s policy choices since the end of the Cold War have upset this strategic “chain,” but also shaken Turkey’s role, casting a pall over Turkish-US relations. The attempted coup in July 2016 and Turkey’s intensely revisionist approach since then – both domestically and internationally – together with its overtures to Russia, have started to openly worry Europe, NATO and the United States. The need to modify the Southern Strategy’s “chain” for containing Russia – deemed as necessary once more following developments in Crimea in 2014 – became apparent to the military leaderships of NATO, the EU and the US the very next day after the attempted coup. Furthermore, Turkey’s blatant attempts to seize the role of regional superpower while its leadership drifted further and further away from Western and democratic principles sowed doubt with regard to its value and role in NATO’s wall of collective defense.

It also became obvious that Greece was the inevitable cornerstone of the new strategy and that Europe’s wall of defense should stretch north to include Bulgaria, Romania and Central Europe, up to the Baltic countries, which also feel the greatest threat from Russia. Greece is a vital part of this new arrangement, as the internal defense line starts from Souda Bay on Crete to reach Alexandroupoli through the islands, and from there to stretch north by land. America’s and Greece’s fleets will provide the “wooden walls” in the Aegean when necessary. The role of the islands in this plan will have to be re-examined at some point. Alexandroupoli is, therefore, key to this strategic approach, mainly with respect to the swift deployment of military forces, and is also a strategically and operationally crucial sea port of debarkation (SPOD).

The reasons for Mr Erdogan’s annoyance are obvious. He is not afraid of the massive US military capabilities being developed at the port of Alexandroupoli. He knows that they will not be turned against Turkey, they will not be there forever and they are not a threat. They are also not a factor in the differences dividing Greece and Turkey. What the president does feel, however, is that he is being left out of the West’s plans as a result of his unpredictable and revisionist behavior, and that Turkey is gradually ending up on the other side of the “wall.”

Ankara is drifting further and further away from modern Turkey’s pro-Western Kemalist leanings, while at the same time failing to pursue a regional role for Turkey that would be acceptable and well-deserved. And the responsibility for all this rests exclusively on Mr Erdogan’s shoulders.

General (ret) Mikhail Kostarakos is a former chief of the Hellenic National Defense General Staff and former chairman of the European Union Military Committee (EUMC).