Whatever happens now, Putin has changed politics in Europe

We are all Leninists now. His words seem to describe what we’re living through: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” Indeed, we’re also living through a polycrisis, with challenges on multiple fronts – security, the economy, climate change, migration etc. Historians in the future will have to weigh the relative significance of each to what comes next. But we can’t wait for hindsight: So, is Putin changing Europe?

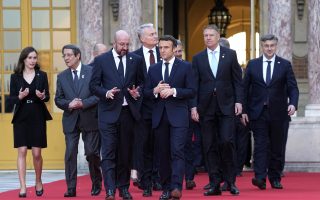

There’s an immediate cause and effect here between Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the European Union signaling a new strategy of developing a stronger security role for itself. In Lenin’s terms, the EU has moved “decades” with its declaration at Versailles and its deliberations at the European Council last week. For more than 50 years, the EU has considered playing a security role and it now has produced its Strategic Compass. That is Putin’s achievement.

Yet the effect remains unclear. The EU will struggle to have its new Rapid Deployment Capacity (of just 5,000 personnel) operational even by the target date of 2025 and its decision rules have still to be worked out. A need for consensus may hamper it.

The key shifts in response to Putin have been at the national level. Germany has crossed a Rubicon and announced major increases in its defense spending. The “reluctant hegemon” has been provoked. And rightly so: It’s too big not to play a role. Significantly, the shift is being made by a Social Democrat/Green government. Similarly, Finland and Sweden are considering ending their neutrality and joining NATO.

For it is the Alliance that has been placed center stage in the Ukraine crisis. The military response can only really come from NATO and the United States. This was clear when the government in Warsaw wanted to supply planes to Kyiv. It could only contemplate doing so via a swap arrangement with Washington and Biden decided “no.”

So, on all likely outcomes for the EU taking up a new security role, it will remain overshadowed by NATO and be dependent on Washington’s leadership. That is the reality of security in today’s world: The EU can never match the role or capacity of NATO. The EU was created for a Kantian world in which states would join together around a set of norms and values. Yet Putin has been behaving as if we’re in a world like the 1930s. The problem for the EU is that it wasn’t designed to play the role of first responder in a military crisis.

But in considering the relationship between the invasion of Ukraine and the EU’s new deliberations about security, perhaps we’re missing changes that may prove to be bigger and more consequential. For there are already signs of deeper sociological shifts occurring that future historians might see more clearly. They are evident in the many demonstrations and protests that have occurred around Europe in support of Ukraine.

Stalin united Western Europe in the Cold War. But Putin might be doing more to help Europe think about its true Kantian values

In short, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is reconfiguring the politics of identity in Europe. Putin has reminded Europe of what it stands for. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s speech to the European Council put Hungary’s Viktor Orban on the spot. He asked him directly: “Do you know what is happening in Mariupol? Who are you for?” Last week, a Visegrad meeting was canceled by Poland and Hungary because they didn’t want to sit down with Orban, in protest at his cool support for action against his former friend Putin.

In the French presidential election campaign, the candidates of the far-right have been put on the spot because of their warm words in the past about the “strong leader” Putin. And Matteo Salvini in Italy is in a similar quandary. The populist right of Euroskeptics have been weakened.

The spread of economic sanctions against Russia (and its oligarchs) have been prompted by waves of public support not seen since the anti-apartheid movement against the regime in South Africa.

So the Ukraine conflict may be bringing out Europe’s better self, reminding it what it really stands for. Stalin united Western Europe in the Cold War. But Putin might be doing more, in the short-term now, to help Europe think about its true Kantian values. The tectonic plates of our domestic political rivalries are shifting and they’re showing who is European and who is not.

So, when Greek MPs listen to President Zelenskyy making his speech to the Greek Parliament this week, it is not a question of avoiding taking sides between “East” and “West,” as if we’re back in the Cold War. It is about Europe having a set of Kantian values. You cannot condemn Erdogan, but equivocate on Putin: They both challenge what Europe stands for.

The biggest result of Putin’s actions may be that he has enabled Europe to have a stronger sense of its values. And the future consequences of that can only be positive.

Kevin Featherstone is Eleftherios Venizelos Professor of Contemporary Greek Studies, professor of European politics and director of the Hellenic Observatory at the London School of Economics.