Landmarks of memory and silence

Thessaloniki was the Sephardic Jews’ Mediterranean metropolis. They found a welcoming anchorage here when they were chased out of Spain in 1492, in the city that became the “Jerusalem of the Balkans.” Their large community grew to great economic and intellectual prominence and represented the largest of the multicultural city’s three distinct quarters during the Ottoman occupation (the Jewish, the Ottoman and the Greek). The Jewish element shrank after the big fire of 1917 and was all but annihilated in the Holocaust, with some 46,000 Greek Jews and constituents of Thessaloniki being lost in the crematoriums. But to add insult to injury, they were also forgotten by their fellow Thessalonians. Not a single public commemoration event was held to mourn the loss of our Jewish compatriots, while the establishment of monuments to pay homage to them and hold their memory alive dragged on for decades.

It was not until 1997 that a memorial to the Holocaust was erected, and it was on the city’s outskirts, far from the Jewish quarter. When the bronze statue was relocated to the city center in 2007, to a corner of Eleftherias Square, the move was met with surprise and denial instead of satisfaction. More memorials have gone up in the past decade – on the campus of Aristotle University, in the area designated as the Jewish cemetery and in other relevant locations. A catalyst in this change of climate was the historic speech given by then mayor Yiannis Boutaris on the National Day of Remembrance of Greek Jewish Martyrs and Heroes of the Holocaust in 2018, which was a long-overdue homage and apology by the city to its lost citizens. However, most of the city’s residents remain indifferent and cool toward the issue, sitting on the tombstones of the Jewish cemetery that was violently demolished by the Nazis and locals who took the marble slabs to use as building materials, even for the forecourt of the Church of Agios Dimitrios.

The tangible Jewish presence in Thessaloniki is still evident in the city’s architectural heritage. Many of the Jews’ residences have been turned to public use, buildings in an eclectic style that attests to the sophistication and prosperity of their former residents. Top among those listed building, which were built before 1912, are the Allatini Villa (now the headquarters of the Regional Authority of Central Macedonia), the Giacomo Modiano Villa (Folklore Museum) and Casa Bianca (Municipal Art Gallery), which is where the turbulent romance between Aline Fernandez, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish businessman, and Greek Lieutenant Spyros Alibertis played out. Several listed apartment buildings from the interwar years, fine examples of the architectural trends of Mitteleuropa, were also owned by Jews.

Only a handful of the public buildings used by the Jewish community survive though: the hospital, a charity that is used today by a Jewish school, and just one synagogue, of the Monasteriotes, which of all the other religious edifices in the city was spared the Nazis’ destruction because it was being used by the Red Cross.

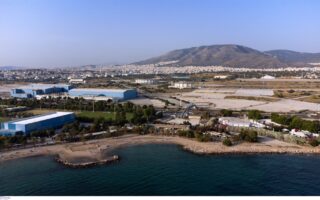

Erstwhile jewels of Jewish industry, like the Fix brewery and the Allatini flour mill, are abandoned husks awaiting demolition.

Several parts of Thessaloniki are associated with the Holocaust: Eleftherias Square, where Jews were tortured in 1942, the old railway station, where 46,061 Jews were packed onto trains for the death camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau between March and August of 1943, and the nearby Baron Hirsch neighborhood, the last ghetto of the Jews before they were put on the “death trains.” Three more spaces – the present-day Jewish Cemetery, the Jewish Museum and Aristotle University – safeguard the memory and stand witness to the lengthy Jewish presence in the “Madre de Israel.”

There is some comfort to be taken from the recent emergence of a multifaceted interest in the history and memories of Thessaloniki’s Jews, mainly from the Jewish community itself and from the Aristotle University, with the contribution of its Chair of Jewish Studies. On the other hand, it is disappointing and peculiar that the present mayor is turning Eleftherias Square back into a parking lot, in breach of the previous municipal authority’s decision and plan to turn the historic location into a place of homage and memory for our lost fellow Thessalonians.

Christos Zafiris is a journalist and a writer. His book “Thessaloniki of the Jews: History, Society, Monuments, The Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki,” published by Epikentro in 2016, is available in Greek, English and French.