From Salamis to Kyiv: 4+1 lessons

Three days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, leading scholar Robert Kagan published an article titled “What we can expect after Putin’s conquest of Ukraine.” Seven months later, the Ukrainian military armed by a US-led coalition has proved many pundits wrong. Several comparisons have been employed to account for the evolution of the war. One that hasn’t yet been made but is nevertheless important is that of the Persian invasion of Greece in antiquity.

The Persian empire at the time boasted a big chunk of the world’s population and arguably the most formidable army in the region that had already begun subjugating Greek states from Ionia to Macedonia. Those that remained free were locked in a bloody conflict with each other. Much like Ukraine, sheer size comparison initially left little doubt about the outcome of the invasion. Let’s examine the parallel lines behind these historical reversals.

Firstly, we have intelligence and organization. The defenders utilized their knowledge of the local battle terrain that Greece provided to negate the devastating Persian cavalry, the historical analogy of the Russian tanks. At Thermopylae and Plataea, the Persians found themselves fighting in rough narrow terrain that practically neutralized their advantage, against a foe that knew the battleground down to the slightest detail. Utilizing crucial US military intelligence, the Ukrainians were able to scan the battlefield to swiftly take out the Russian tanks and their decentralized organization has been able to outflank the Russian Army, which relies on centralized commands from above, leaving little initiative to the combat units.

Secondly, it’s mobility. The first major problem the Greeks had to face were the world-renowned Persian archers. To counter their overwhelming volleys at Marathon, general Miltiades ordered his disciplined hoplites to surge against the enemy archers and hack them down before they unleashed their arrows. The Russian artillery also had a fearsome reputation killing from afar; before Ukraine, it had reduced the cities of Grozny and Aleppo to rubble, successfully furthering the Kremlin’s interests in Chechnya and Syria respectively.

Relying on small, agile units the Ukrainians were able to counter the enemy artillery superiority and respond with sudden strikes.

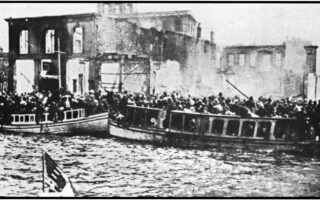

The third parallel concerns weapons. When an Athenian was confronted with the unimpressive looks of a Spartan’s kopis, the short sword they used, the Spartan famously replied that “it’s long enough to reach the enemy’s heart.” Today, 2.5 kg US Switchblades (unmanned drones) can neutralize tons of Russian armor. In the same way, two R-360 Neptune missiles worth a few million dollars sank the Russian flagship Moskva, the first since the 1905 Russo-Japanese War. The nimble Greek vessels in the naval battle of Salamis were likewise able to outmaneuver and sink their bigger and heavier Persian counterparts. Effectiveness is not necessarily commensurate to size.

The fourth parallel covers morale. The hoplite phalanx functioned like a multi-person armor, hacking through the enemy lines while itself remaining impenetrable. That required training but also the willingness of civilians to actively partake in the war effort – indeed, to find themselves from the agora straight into the front line. Ukrainians have received massive aid in terms of weapons, intelligence and training, but it would not suffice without the determination to defend their country. Russian soldiers, on the other hand, are fighting in an army that invaded a brother nation: assaulting the very cities where their fathers and grandfathers lived in peace.

The defenders utilized their knowledge of the local battle terrain that Greece provided to negate the devastating Persian cavalry

That leads to the final parallel: state structure. How did some squabbling Greek states manage to gain the edge in military organization, morale and technology against the world’s largest empire?

The foundations for the Greek victory were in fact laid centuries before the clash. Beginning in the 6th century, several states began to gradually experience a shift of power in favor of an emerging middle class. Oligarchies started to cede ground to city assemblies, their estates to be replaced by small farms. Trade flourished; no city could attain autarchy in mountainous Greece and hence initiated routes of exchange with other states. Thus rose a maritime culture of openness and innovation and also a strong merchant class that pushed for additional private property and commercial rights. The latter was key in the increased significance of city-states and a major factor driving the rise of democratic tendencies. The new economic situation provided a newly empowered class of citizens with the means to afford to bear armor, while the political landscape armed them with a sense of responsibility to use it to defend their lot. To the effectiveness of the Persian imperial autocracy with its centrally planned economic system, the Greeks countered with the chaotic urban assemblies and their market system and emerged victorious.

Similarly, the West backing Ukraine today has managed over the centuries to create institutions that ignited prosperity and also secured its advantage in terms of organization, intelligence and military capabilities. All have allowed Ukraine to outgun and outperform the Russian Army. Can, however, Western institutions themselves preserve this edge in the 21st century?

President Vladimir Putin believes otherwise. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Chairman Xi Jinping follow suit. And during the last 20 years, so do more and more states around the world. Hence now it’s the Free World that is dwarfed by their combined size, just as its Greek ancestor was by the Persian empire: Liberal democracies now boast less than a fifth of the world’s population. To keep outperforming their competitors, liberal democracies will have to build upon the “quality vs quantity” legacy of Greco-Persian conflict.

The very size of autocratic enterprises is daunting. That is, after all, their purpose. To reign over the unruly Hellespont, Xerxes made a gigantic bridge out of his numerous vessels, after ordering the sea to be whipped for its insubordination. The Persian wars serve as a dependable guide for confronting his contemporary imitators.

Gerard Roland is the E. Morris Cox Professor of Economics and Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley, and Nikolas Neos is an economist.