Erdogan’s nets in the Balkans

Why are the Turkish president’s efforts to spread his influence among Muslim populations falling on deaf ears?

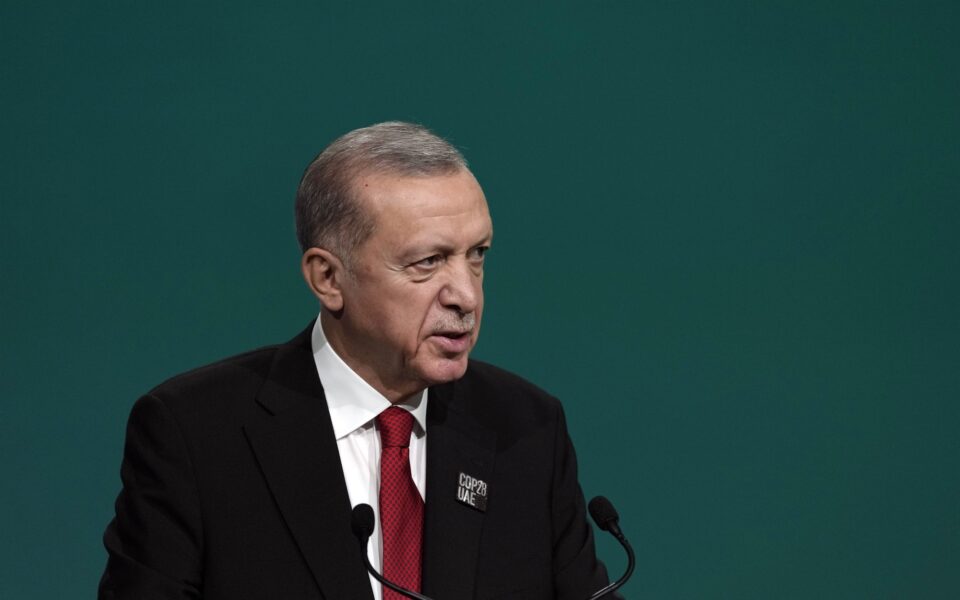

In a recent speech in Istanbul, Recep Tayyip Erdogan donned the mantle of leader of the Muslim world and spoke of the “geography of his heart,” with crowds of Islamists responding with the slogan “Here is the general, here is his army.” But these are not sentiments that the “general’ seems to be able to export outside Turkey.

In AD 1521, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, having just conquered Belgrade, declared with greatness that he would go as far as “where the last Christian bell tolls.” His dream was wrecked on the Danube; before the walls of Vienna his armies were crushed by those of the Christian allies and he was forced, humiliated, to retreat to the lands of what is now Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Five hundred and some years later, another Turk, this one a president with the rhetoric of a sultan, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, envisions the reconstitution of a new Ottoman Empire – he calls it the “Blue Homeland” – that will reach west to where Suleiman arrived, a route that passes through Thrace, Thessaloniki and Skopje and east to China…

Under the mantle of the protector of “all those who suffer and are in pain,” that is to say, of Muslims, he “unfolds” the map in his mind. “Thessaloniki, Skopje, Mosul, Jerusalem, we see them as we see our own cities, the geography of our heart reaches from the Adriatic to the Great Wall,” he proclaims, with crowds of fanatical Islamists responding to gatherings of 1 million, such as a recent one in Istanbul, chanting, “Here is the general, here is his army.”

The question is whether his grandiloquence resonates with the recipients, and in this case with the solid Muslim populations of the Balkans, whom he aspires to bind firmly to the Turkish “chariot.”

Israel’s ‘punisher’

One would have expected that the banner of Israel’s punisher and even more so of the “liberator” of the Palestinians would light a fire in the souls of his millions of fellow believers in the Balkan region, whom Erdogan considers a “force in the struggle for his imperial greatness,” as the German newspaper Die Welt put it. However, this has not been the case.

There were some rallies in cities such as Sarajevo, Belgrade and Skopje, with the participation of Muslims and Christians alike, the media covered the events as everywhere else, but the Turkish president’s sermons about the uprising of Muslims everywhere in the name of Allah were met with indifference by Muslim societies. He has not been discouraged. Since the beginning of 2000 when he came to power, a mild Islamist at first, he has been touring the Balkans where historically Turkey has toyed with the Muslim populations.

He doles out money, gives loans for major construction projects, sells arms, prays in mosques he repairs or finances, and after 2016, persecutes “terrorist” Gulenists. The majority of Balkan Muslims, however, carry a sense of cosmopolitanism in their DNA. They have learned in the depths of the centuries to live peacefully with Christian populations and have their eyes on the West.

The novel “The Bridge on the Drina,” by the Nobel Prize-winning Bosnian author Ivo Andric, is an outstanding text describing the centuries-long harmonious coexistence of four different nationalities, religions, and cultures in Bosnia.

Indeed, young Muslims are emigrating en masse to France, Germany, Italy, Britain, Sweden and the US in search of a better life there and not in Turkey, Saudi Arabia or Egypt – proof that the religious paternalism of the Turkish leader does not move them.

Pounds yes, identity no

On the other hand, Balkan Muslims – like Christians – do not say no to Erdogan’s investments and money.

They (the former) acknowledge their religious affinity and historical ties with Turkey, but the vast majority of them do not feel in any way Turkish, nor do they show any inclination to discount their identity. They have even shown on more than a few occasions that they resent Erdogan’s insistence on tying them to the Turkish “chariot.” As in 2013 when Erdogan, speaking at a rally in Prizren, Kosovo, proclaimed that he felt the newly independent state was his second homeland and that the two peoples, Turks and Albanians, belonged to the same country. “Kosovo is Turkey and Turkey is Kosovo!” he declared.

He did not expect that his words would provoke a storm of reactions not only from foreigners such as Serbs, but especially from his co-religionists.

And he heard them well and truly. Albanian author Ismail Kadare has repeatedly shown in his writings that he holds the Ottoman occupation responsible for the situation in which the Albanian nation finds itself. “What I have written is very timely. The so-called Slavic danger of the disappearance of the Albanian nation was an invention of the Ottomans and the neo-Ottomans,” he said.

Relations between Ankara and Belgrade were tested after this for a while. “Serbia cannot take these statements as friendly,” the Foreign Ministry said, with Aleksandar Vuviv demanding “an urgent public apology” from the Turks.

One of Erdogan’s visits to Tirana in 2022, on the anniversary of the death of the Albanian national hero in the liberation struggle against the Ottomans, Gjergj Kastrioti, better known as Skanderbeg, was seen by a large part of the public as a provocation. The then-president Ilir Meta avoided meeting with him and while Erdogan was delivering a speech praising Albania’s Ottoman past, he preferred to go to Lezhe to lay a wreath at Skanderbeg’s monument.

Interventions

Erdogan is certainly not sweating over all this. Turkey is working strategically and at a high level in the Balkans, attempting to intervene in ethnic conflicts and internal political developments.

It has been relatively successful, at the government level, in attempts to bring Belgrade and Sarajevo together on the issue of the Srebrenica massacre, and it is openly claiming a mediating role in the dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina, to the point of irritating the Albanians. The response from the Pristina government was: “Thanks, but no thanks. This dialogue is being conducted under the auspices of the European Union.” Half a millennium after Suleiman hurled his threats toward the Christian West from Belgrade, Erdogan chose to hurl his own toward the West from Bosnia, as that was the European border of the Ottoman Empire.

In an election speech on May 20, 2018 in Sarajevo, in the presence of 15,000 Turks from various countries, he urged them to become active in political parties and to seek seats in parliaments. After the Muslim populations of the Balkans, it seems that Erdogan is attempting to put the armies of Turks in Western Europe on alert as their political and religious “godfather.”

The Turkish leader is trying to inspire his fellow believers by reselling them the vision of Suleiman the Magnificent. Bosnians, Albanians and Kosovars accept Ankara’s investments but oppose its intention to interfere in their relations with Belgrade.