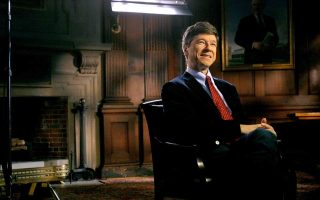

Joseph Stiglitz discusses ‘value crisis’ at Davos, Greek crisis

Joseph Stiglitz is a Davos veteran. The renowned economist and winner of the 2001 Nobel Memorial Prize has attended dozens of World Economic Forum sessions in a number of capacities (including vice president of the World Bank and chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under the Clinton administration).

A self-proclaimed Hellenophile, he is particularly interested in Greece, having served as an adviser to George Papandreou’s government and vocally expressed his support for the “no” vote in the heated 2015 referendum.

At this year’s Davos, amid American optimism over Trump’s tax cut policy and the rise of cryptocurrencies, Stiglitz found himself swimming against the tide. He met with Kathimerini for an exclusive interview on a chilly Thursday morning, when he talked about the values crisis of this year’s WEF, gave his take on the future of globalization, and how his opinion on Greece and the SYRIZA government has evolved over the years.

You have attended Davos for more than 30 years. What keeps bringing you back and what would you say is different about this year’s WEF?

I have a lot of admiration over the fact that Davos has always brought three distinct groups together. There’s the top business owners of capitalism, academics – many of whom are social democrats – and young global leaders who are typically very different in spirit than the elite. But there are two deep values that I find common to all three. The first one is a belief in globalization, in open society, the rule of law and the instrument of the market economy. The second is the benefit of technology. Davos is a gathering of techno-optimists, for the most part.

There has been an interesting change in the past few years: namely Trump, and his campaign. He is anti-globalization, anti-openness and in many ways comes from a sector of the economy that’s the opposite of Silicon Valley. So you could say Trump is in many ways the antithesis of Davos. He arrived with a protectionist, anti-climate change agenda, having passed a tax bill that is the most regressive taxation that any democratic country has ever passed. He left 13 million more people without health insurance, and raised taxes on a majority of people in the second, third and fourth quartiles. But he arrived as the economy is finally recovering from the crisis of 2008. You see this recovery strongest in Europe, so it is clearly not the result of Trump but more a factor of time. But in Davos, we saw almost no criticism against his policies from the Americans.

In fact there has been an echo of celebration of his tax cut reform from American CEOs. Would you say that Trump has been normalized?

Yes, that’s exactly right. Last year there was hope that Trump the President would be better than Trump the Candidate, that he would eventually move into statesman mode. Many business owners joined the councils in hope that they might have influence over him. We now know that he is worse, and the fact that it took them so long to recognize this is deeply disturbing.

In the way business owners are reacting, I see a clear contradiction between the values and the policies. Trump is aligned with the policies that make them richer, but not with the espoused values. A year into his presidency, he has attacked the media, the judiciary, the intelligence – almost every single one of our institutions. And yet, that’s put below the fact that he is promising deregulation and a tax cut for the rich.

Apart from Trump’s protectionism, when it comes to other Discontents of Globalization there is a new doctrine represented by Jeremy Corbyn. He is in favor of increased state control and nationalizations. Is that a viable response to the problems of globalization?

Let me put it in more broadly. If we operate on the premise that globalization is good, the gains have to be such that at the minimum those who benefit have to make sure that very few are left behind. The mechanisms can of course differ from society to society. The most successful have been the Scandinavian countries, with active liberal market policies and an almost explicit social contract.

I think this is the most viable response to globalization and this is somewhat what Corbyn is trying to do. Where I differ from him a little bit is that I think he’s been too influenced by 19th century ideas of renationalizing. At the same time I think it’s understandable in the British context, because there is a history of bad privatization, an ideological and corrupt process of outsourcing. I wouldn’t call it nationalization, I would call it remedying the failures of the Thatcher era.

Let’s talk a little bit about cryptocurrencies, which was the expression of the moment at this year’s WEF. You have predicted they are doomed to fail – why is that and why is Davos not thinking the same way?

I think, again, a lot of the Davos attendees are thinking about ways to make a profit, but they are missing the bigger picture. First let’s ask, what is wrong with the dollar? It is a good medium of exchange and its stability has been amazing over the past 40 years. Bitcoin on the other hand is not stable, so really the only justification for it is secrecy – the demand for things like tax evasion or money laundering. It seems to me that the moment bitcoin becomes important enough, governments will shut it down, because they can. By shutting it down I mean asking for openness and transparency, which will make bitcoin redundant.

Beyond the risk of regulation, there is also a problem of supply. While the supply of bitcoins is limited as a mathematical algorithm, there is no limit to the supply of other algorithms. Already new cryptocurrencies are being created and, in fact, there is an infinite number of currencies one can create. So the moment the price gets very high, you can bear the price versus the cost of production and create new currencies. The long-term price is bound to go down.

Let’s talk about Greece, where you have been quite vocal in the past, especially at the peak of the 2015 negotiation process. This year we have started to see signs of sluggish growth and hear narratives of an economic recovery. How do you evaluate those?

I think what has happened in Greece is a normalization of poverty. I see no real recovery yet, I just think the economy has fallen so far that it’s almost inconceivable for it fall further. But I don’t see a reason to celebrate depression continuing, but not getting much worse. I think Greeks are finding way to cope as a society, but the long-run effects on society are devastating. The good side of Europe is that you can move freely and seek opportunity, the downside is that young people are now leaving Greece behind to seek jobs. It’s like a cultural genocide.

In 2015 you expressed your support for the SYRIZA government. Three years later it has backtracked on its promises and implemented many of the policies it was fighting against. Has your opinion of SYRIZA and Alexis Tsipras evolved since then?

I have been disappointed that they were not brave enough. I totally understand the fear of leaving the eurozone, but my view was in balancing the risks. If Greece had chosen to leave the currency, its economy would have gotten worse initially, but it would have recovered and done very well.

At the same time, there was no such mandate at the time. Estimates show that between 60 and 70 percent of Greeks want to remain in the euro.

Many Greeks that I talk to confuse leaving the euro with leaving the EU. I think if SYRIZA had pushed further, it would have confronted Europe with that difficult dilemma. Officially Europe says you can’t be part of the EU without the euro, but now we see that de facto Sweden will never join the euro. I think that proves that their language was not going to be implemented. Greece could have been like Sweden, within Europe but without the currency.

In Greece many see a version of the globalization dilemma that you express in your books: the benefits of being part of Europe, but also the problems with some of its mechanisms. What lessons can we draw from Greece when it comes to globalization and the rise of populism worldwide?

That’s a really good question. I think the lesson is that there is still so much diversity that you have to balance the mechanisms of flexibility with the mechanisms of harmonization.

You can’t force the pace of integration. I don’t think that in my lifetime or even in that of others there will be enough similarity that a single system would work for the world, or even Europe. I think Greece shows us the challenges to decentralization, and reminds us that we still need to figure out the optimal degree of integration.