A digital ‘atlas’ of the refugee imprint in Greece

Initiative launched to create an open database illustrating the economic and political impact of the ethnic Greeks who fled Asia Minor

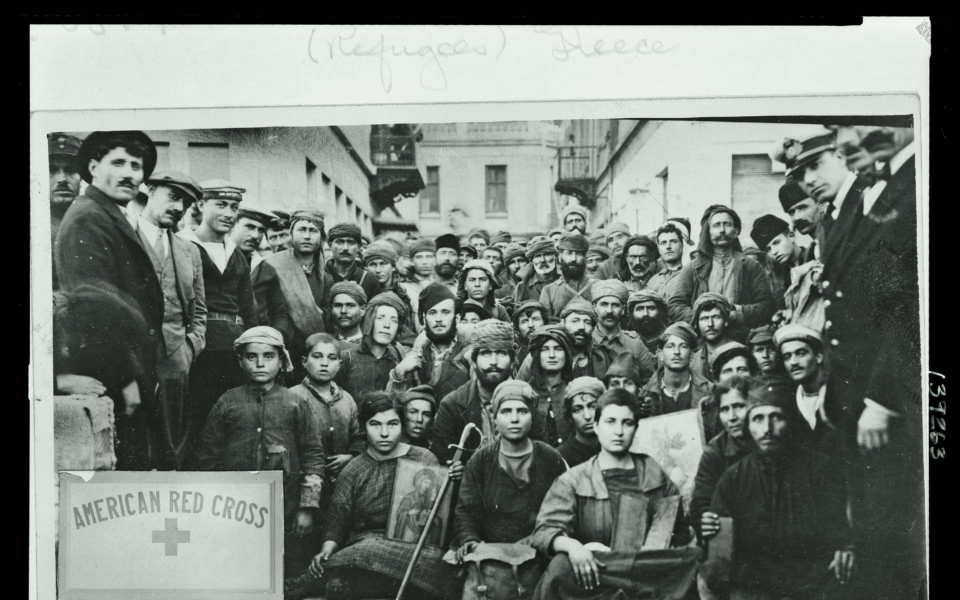

Is the trauma of displacement enduring? What is its impact – on the economy, on electoral behavior, on art – even decades later? How is a society affected when it suddenly needs to take in a large number of refugees?

Anatolia Imprints (http://www.anatolia-imprints.gr) is an ambitious and labor-intensive project aimed at scientifically recording the economic, political and social impact of the decade-long wave of refugee arrivals in Greece that peaked in 1922-23. The website includes an interactive map that allows users to find out which part of Turkey their ancestors came from and where they settled in Greece – it covers all the refugees from agricultural communities and nearly half of those from cities – simply by inputting their full name. The visual depiction of the data allows users to see the dispersion of displaced individuals from a specific community in Turkey throughout Greece, and conversely, the different places from which the Asia Minor refugees arrived at each Greek village or city.

Two distinguished economics professors of the Greek diaspora are the driving force behind the project: Stelios Michalopoulos from Brown University in the United States and Elias Papaioannou from the London Business School. They set out, they tell Kathimerini, to use the tools of economic science and new technology to examine the effect of the huge refugee wave on Greece in the 1920s and on successive generations from a new perspective.

“This research project is important at many different levels and is expected to yield some very interesting results,” the general director of the Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), Nikos Vettas, tells Kathimerini. “The first reason is that it uses a combination of methods from different sciences and technological approaches. It is also a good example of the evolution of economic science, which can incorporate elements from psychology, history or sociology at its core, as well, of course, as modern methods of data analysis.” Vettas adds that Anatolia Imprints is creating vital databases for future research projects, “an area where there is a definite dearth in Greece.”

Principal components

“The first task we focused on was digitizing the 1928 census, which represents the first and only time that citizens have been asked to state their origin in order to differentiate between refugees and natives,” explains Papaioannou. This process allows the depiction of refugees in approximately 11,000 settlements, villages, towns and cities across the country. Out of a total population of 6,204,684, the number of refugees came to 1,221,849 (19.7%). Of them, 1,069,957 came to Greece after the Asia Minor Catastrophe. “Even though the census also listed children born in Greece to refugee parents as refugees themselves, the number of actual refugees is probably larger, as mortality was high and many refugees had gone on to immigrate to other countries before 1928,” notes the London Business School professor.

The second order of business, the two economists tell Kathimerini, was to turn to the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) for microdata from the general population censuses of 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011, from which they gleaned information about education levels, employment per economic sector and living conditions in Greece.

Detailed data on the composition of the population of every village allowed fruitful comparisons between neighboring settlements, both those of refugees and of non-refugees. One of the interesting findings that emerged, according to Michalopoulos, is that being uprooted appears to create a predisposition for further migration.

“The difference in the trends toward immigration to Germany between refugee and non-refugee settlements was very significant in the 1960s, at around 35%,” says the Brown University professor. Moreover, the trend of internal migration from rural areas to cities after the Civil War was much stronger in refugee villages.

One of the “myths” the research debunks, according to Michalopoulos, is the educational level of the refugees. Contrary to popular wisdom, “the first generation was clearly less educated than the native Greeks. What is striking is that the refugees made up for this with remarkable speed so that, within a decade, they had surpassed the local population.”

Papaioannou and Michalopoulos surmise that the educational reforms introduced by Eleftherios Venizelos, which included the construction of 3,000 schools between 1929 and 1932, were instrumental to the speed at which the refugees acquired a better education. These findings, they further argue, “stem from a significant body of literature which indicates that having been deprived of their land, their wealth and their possessions, the refugees invested in human capital, which, as opposed to physical capital, can never be taken away.”

The research also shows that refugee villages and towns became local hubs of industry as their residents, women to a large degree, worked in textiles and manufacturing, mainly. In combination with the work they did in the industrial sector in cities, refugees emerged as a driving force in the structural transformation of the Greek economy from an agrarian one to an industrial and service-based one.

The registers

Another important contribution from the project was the digitization of the registers of rural and urban refugees from the Refugee Settlement Commission (EAP), which took on the Herculean task of recording, assisting and integrating the refugees in the mid-1920s. It was a project that is justly characterized as one of the greatest accomplishments of the Greek state. The registers, which record refugee households, run until 1928-29, says Michalopoulos. “They are related to the asset assessment committees.”

For the 250,000 rural farming families, the registers contain full names, their provenance and where they settled in Greece, mainly in some 2,000 villages where they were given land to cultivate. As for the refugees who settled in Athens, Thessaloniki, Piraeus and other big cities, the registers only provide the full name of the head of the household and the place of provenance. “Instead of land, the urbanites were given promissory bonds,” says Michalopoulos.

The team of Anatolia Imprints managed, before its funding ran out, to digitize about half the 340,000 urban refugee households. “We needed another year. We’ll get back to it, if we pluck up the courage,” says the Brown University academic.

Electoral behavior

The researchers also digitized the electoral rolls of Attica’s refugees, based on which they voted during the years 1923-24. “Processing these registers allowed us to get their names, surnames and, most importantly, the professions of the refugees immediately after their violent displacement and settlement in Attica,” explains Papaioannou.

The team additionally digitized the results of the 1932, 1958 and 1977 general elections and analyzed them against the results of recent polls from 2007-2019, which are already available in digital form.

Vassilis Logothetis from the University of Ioannina’s Department of Economics took part in this leg of the project and tells Kathimerini that the experts “noted a distinct difference in political behavior between the refugee and non-refugee parts of Athens, Piraeus and Thessaloniki, which has endured over time.”

In 1932, he notes, “Venizelos’ influence was greater in refugee neighborhoods, as was that of the communists. The Popular Party, in contrast, lagged significantly. In 1958, EDA [the United Democratic Left] had a greater influence over refuge populations, while ERE [the conservative National Radical Union] was more popular among non-refugees. In 1977, meanwhile, socialist PASOK and communist KKE had their best performance among refugee populations, while conservative New Democracy did better among non-refugees.”

“The differences are even evident within municipalities, between different neighborhoods and polling stations in close proximity to each other,” adds Logothetis.

Sources

As mentioned on the project’s website, the sources for tracing the refugee settlements seen on the map included original blueprints for the settlements, mainly from the archive of the EAP, which is now held by the United Nations Digital Library and the General State Archives. They also include blueprints for Greek towns and, via secondary sources, zoning and architectural plans, not to mention information collected by local associations representing the descendants of the refugees.

Maps of the suburbs and neighborhoods settled by refugees in Greek cities will be published in the next few months. An automatic application that categorizes surnames according to the likelihood that they have refugee roots will also be put into operation. This is accomplished thanks to a machine learning method the researchers have already used on the electoral rolls in Athens in 1924. Additionally, the team will publish an analysis of Greek music from 1920-2020 tracing whether the artist comes from refugee stock on the basis of the lyrics.

The springboard

The Anatolia Imprints project stems from the 2017 funding of a research program by Stelios Michalopoulos by the National Science Foundation in the US and was bolstered further with research grants received by Elias Papaioannou, mainly from the Wheeler Institute in the UK.

“It was a time when economists, especially in the United States, took a particular interest in refugee flows,” says Michalopoulos. “It was a time when [then US president Donald] Trump talked about building a wall [on the southern border with Mexico] and there was much discussion about what happens when a country experiences major population shifts, who is left out etc.”

The difference with their project, he explains, is that it seeks to record the impact of large inflows over the long term – almost to the present, in fact.

“This was something that suited both of us,” adds Papaioannou. “We have both studied economic history and the persistence of certain characteristics over time, such as the enduring influence of colonization on the state of many countries in Africa today. This is what we wanted to explore in the case of the 1922 refugee influx and its impact on their descendants – why something which happened 100 years ago continues to come up in conversation, why people still talk about the trauma experienced by their grandparents or great-grandparents.”

“How the new populations were assimilated matters for Greece today if it wants to have a more dynamic point of view on maintaining, attracting and integrating more new populations in the years to come,” adds Nikos Vettas.

The team that collected, processed and digitized the data is made up mainly of graduate and postgraduate students, most of them from the University of Ioannina’s Applied Informatics and Computational Economics Lab, under the supervision of associate professor in economic sciences Athanassios Stavrakoudis.