Princelings of the Polytechnic

Pity the poor princelings of the Polytechnic, those rebels with no regime to fight against, who confuse the symbolic buildings that they occupy with history itself, who think that the fumes of their Molotov cocktails make them equal to those who fought the junta in 1973, who, instead of clashing with tanks, burn trolley buses. Dressed in the accoutrements of anarchy, scuttling about in the anti-establishment shade, they have become a regime unto themselves. What do you call bull fighters who face not bulls but cows? Butchers. What do you call those who impose their will, their fantasies, on the rest of society and fear no punishment? What do you call those who ride on the coattails of historical movements while undermining whatever legitimate protests the future holds, when their targets are not capitalism or imperialism but taxpayers and the poor?

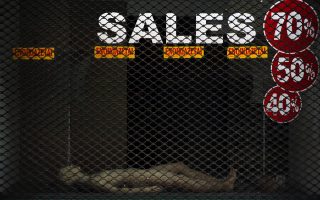

In their wish to make utopia reality, the fantasist revolutionaries who have taken over the Polytechnic building have one success to their name: They have turned the most banal bit of reality – riding a trolley bus in central Athens – into a utopian dream. It is worth looking at their latest achievement, burning three trolley buses last Monday, in the context of other events of that day. A truck sowed death in central Berlin and more terror in Europe; a few hours earlier, a Turkish policeman assassinated the Russian ambassador in Ankara; new twists in the never-ending negotiations between the Greek government and our creditors meant a further wait for an end to our economic and social limbo. We Greeks are fortunate, then, to not have serious problems, where we have the luxury where some destroy public property and others see this as normal.

The most tragic aspect of the rebels of Exarchia is that they see themselves as protagonists but they are just symptoms of a greater disease. The tolerance with which the state treats them shows that it is afraid of tackling them and, to some extent, many in positions of authority identify with them. This confusion has plagued society for many decades, if not since the beginning of the Greek state. When the establishment is continually seen as unjust, lacking credibility and vulnerable, when the implementation of the law is not automatic but subject to barter and “political” settlement, then there is no right and wrong, no difference between the just and the unjust. All that matters is what we want and what others impose on us.

This mentality determines developments – from the highest office to the streets. Because we believe that we are in the right, we do not see the need to play by the rules – and we do not expect others to do so. Soccer is a good example, where fans see any loss as the result of cheating, whereas victory is always because they have the better team. They do not measure the worth of the other side.

That is why we have learned to play alone. Our politicians cannot cooperate with each other; like fans they are addicted to the need to stamp out the opponent. In the same way, today’s “rebels” see nothing awkward in their having become part of the establishment, in having no state fighting them. And so young people who care about their future emigrate. And governments which act like champions inside Greece find themselves continually dependant on partners and creditors.