A chance to tell the euro story in full

Maybe the dial in his mind was still switched to the rigors of the Dutch elections, or possibly his focus was on former colleagues who might now want to challenge him for his post as Eurogroup president. Whatever the case, Jeroen Dijsselbloem exposed one of the ugliest and most damaging sides of the discussion about the eurozone since the crisis broke out.

“The north of the eurozone showed solidarity,” he said in an interview with Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. “Solidarity is very important but those demanding it have duties too. I can’t spend my money on alcohol and women then ask for help.”

His comments were labeled as divisive, racist and sexist. Southern European countries felt that what Dijsselbloem said was an unfair, insulting caricature. Calls for Dijsselbloem’s resignation came from Portugal and Italy, while the Greek government condemned his remarks as being “unhelpful.”

The Dutch finance minister, who may be out of a job soon after his Labor Party gained only nine seats in the recent elections, passed up the chance to apologize during a session of the European Parliament’s Economic Affairs Committee on March 21.

“Solidarity comes with strong commitment and responsibility,” he said, insisting that he had not been referring to the south. “Otherwise, solidarity will not hold. It cannot be upheld. You will not maintain public support for solidarity if it doesn’t come with commitment and responsibility and an effort from all sides.”

Dijsselbloem later expressed regret that his original comment was misunderstood and put it down to “Dutch directness” and a strict Calvinistic culture. Nevertheless, he may now find it difficult to remain Eurogroup chief, a position he gained despite having relatively little experience.

During his term he has had to deal with the Cyprus bailout, a flaring up of the Greek crisis and the antics of Yanis Varoufakis, among others, which would have tested men of greater experience. He also appears to have made a genuine attempt to broker a decisive deal between Greece and its lenders at the December 5 gathering of eurozone finance ministers, ultimately falling short. We should avoid confusing our analysis of Dijsselbloem’s recent comment with an assessment of his time in office.

The ideas that the Dutch finance minister expressed are highly problematic and extremely pernicious. They need to be addressed separately. They go to the very heart of the latent racism that has existed in some of the European media, politicians’ rhetoric and the popular narratives that have taken root since the euro crisis began. They also correlate with the faux-moralistic approach to crisis management that has driven a wedge between the core and the periphery, while compounding many of the problems it was meant to address.

There are two key issues that need to be addressed. The first is the idea of solidarity, which has been a buzzword for eurozone policymakers. The definition of solidarity is when groups or individuals act together for a common purpose. However, when European officials talk about solidarity in the context of the euro crisis, they present it as a one-way transaction: The program countries were in danger of going under but were rescued with loans provided by their partners.

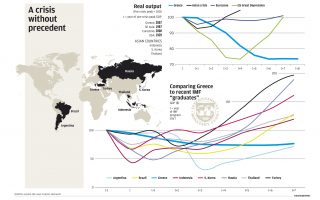

This is not false but it is a very limited interpretation of what has happened over the last few years: Members of a single currency that lacked fiscal unity and the tools to deal with a crisis ran into economic problems and were bailed out with loans that came with strict conditionality. Although this staved off disorderly defaults and the pain they would bring, meeting the bailout conditions put a severe strain on the economies of the countries concerned. They put their public finances in order, they embarked on structural reforms and endured falls in their economic output and rises in unemployment levels.

At the same time, some of the eurozone member-states providing the loans were able to shore up their defenses against a crisis in their banks, which had lent freely to the bailed-out countries in previous years, and within their eurozone. While they put up the firewall, Spain, Cyprus, Portugal and Greece felt the heat of shuttered businesses, job losses and rising emigration, especially among their young people.

The other point that needs to be made about Dijsselbloem’s comment is in relation to the impression created (inadvertently, the Dutch politician argues) that the crisis was a result of the profligate south wasting its wealth. Apart from the fact that this conjures up a nasty image, it is a misreading of how the eurozone worked.

It is true that the onset of the crisis found Greece, Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Italy with a collective current account deficit of almost 7 percent of their GDP. But the core, including Germany and the Netherlands, recorded a surplus of around 6 percent of their GDP.

As economists Alexandr Hobza and Stefan Zeugner point out in a 2014 European Commission paper they wrote, the euro area’s overall current account “stayed moderately positive,” never exceeding 1 percent of GDP. “The euro area current account position during its first decade thus could be called an ‘imbalanced balance,’” they write. “This implies that the deficits were almost exclusively financed from the surpluses in other euro area countries.”

What the eurozone witnessed in the buildup to the crisis was a “downhill” capital flow from the core, which was capital-rich thanks to excessive savings, to the periphery, which was in a hurry to catch up with its partners in the newly created euro. The crisis brought these flows to a sudden stop.

Had the periphery invested its newfound (borrowed) wealth wisely? In many cases, it hadn’t. However, to suggest that this was the only problematic part of the transactions is patently wrong. Where there is bad borrowing, there is also bad lending. The latter part, though, seems to have largely been airbrushed out of the euro crisis story. In Greece’s case, the discussion centers almost exclusively on the wasteful public spending and hardly ever on the equally reckless lending.

To ignore this fundamental aspect of what led to the travails of the last few years suggests that eurozone policymakers are not genuinely interested in using the crisis to strengthen the single currency as a whole and each of its members individually.

It is disheartening that these issues should be a topic of discussion in the eurozone so many years after the crisis began. Perhaps Dijsselbloem’s words – whatever his intention – can provide an opportunity for a rebalancing, for the story to be told in full and for stereotypes to be shattered.