A fiscal target beaten, but at what cost?

After months of to and fro, claim and counter-claim, we now know that Greece’s primary budget surplus for 2016 came in way above its target, leaving us with another Greek crisis paradox to ponder.

Just as talks between Greek government officials and representatives of the country’s lenders were due to get under way on the sidelines of the International Monetary Fund’s Spring Meetings in Washington on Friday, the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) announced that the general government primary surplus reached 3.9 percent of gross domestic product last year (or 4.2 percent under the rules used for Greece’s bailout program). The target agreed with the lenders for 2016 was 0.5 percent.

On its own, the figure seems astounding, especially when one considers that capital controls continued to be a hindrance last year and that an economic growth spurt was soon killed off by the uncertainty over whether there would be an agreement between Athens and the crediting institutions on how to conclude the second review of the Greek program.

One of the key disagreements in the protracted negotiations, which seem to be drawing to an amicable close, was over fiscal targets. The IMF doubted that Greece could reach the 3.5 percent of GDP goal it was set for 2018 and the medium-term beyond without additional measures. The Fund also argued that such a high target should not be kept for too long because it is unrealistic and damaging for the economy.

In the end, the compromise in the making will see Greece adopt another 2 percent of GDP (or 3.6 billion euros) in new fiscal measures, half in 2019 and the rest in 2020, to ensure that the 3.5 percent primary surplus target is within scope, while the eurozone will agree, in turn, to provide medium-term debt relief and limit the high fiscal targets demanded to just a few years (less than five, it is thought) before they drop to levels that the IMF considers more logical.

There is a great deal of irony in the fact that the wrangling of the last few months was driven by the IMF disputing the eurozone lenders’ fiscal forecasts for Greece, only for the figures published by ELSTAT on Friday to suggest that there were hardly any grounds for such a dispute to develop.

A day before the 2016 primary surplus figure was made public, the IMF issued its Fiscal Monitor report, in which the Washington-based organization made a timely revision of its forecast for last year. In the previous Fiscal Monitor, published last October, the IMF had predicted that Greece’s primary surplus in 2016 would reach just 0.1 percent of GDP. On Thursday, it put the same number at 3.3 percent, which represented an almighty revision and one that was much closer to the figure produced by ELSTAT.

In comments to journalists in Washington on Friday, the director of the Fund’s European Department, Poul Thomsen, suggested that the IMF may have overestimated the impact that capital controls would have on the Greek economy, causing its fiscal forecasts to be much more pessimistic than the ones made by the European creditors.

However, a Bloomberg report last week claimed IMF officials believe that possibly more than half of last year’s primary surplus was the result of one-off measures rather than structural factors. This is one of the reasons why the extra fiscal interventions the Fund has called for will remain part of the agreement between Athens and the institutions and will have to be voted through Parliament in the coming weeks so there is a chance of reaching a so-called “global deal,” including debt relief and revised fiscal targets, at the May 22 Eurogroup.

With a settlement that could pave the way for Greece’s successful exit from the program in the summer of 2018 in sight, and regardless of the all-round damage that it caused, the recent squabble over fiscal performance has already been consigned to history.

What cannot be set aside so easily, though, is the feeling that regardless of whether Greece has to achieve a primary surplus of 3.5, 2.5 or 1.5 percent of GDP over the next years, it will continue to swim against the tide until there is a strong, genuine and lasting growth in the country.

The paradox is that chasing these large surpluses is a severe obstacle to this kind of economic development.

To have gone through a Brobdingnagian fiscal adjustment since 2010 against the backdrop of a deep recession and still be producing a primary surplus of 3.9 percent of GDP seven years later is an incredible achievement. It is also immensely damaging, though.

Although Greece’s once-tragic public finances have been brought under control, this has come at the cost of choking the life out of the local economy. The fiscal targets have been met and exceeded by paring back spending and piling more taxes onto individuals and businesses that have seen their wealth and resources dwindle over the last seven years.

This was underlined by recent data released by the Independent Authority for Public Revenue, which provided an insight into the changes in personal income tax declarations and payments over recent years.

The body found that although there was a 9 percent increase in the number of taxpayers between 2010 and 2016, and the tax due increased by 10 percent, the income declared during this period plummeted by 23.3 percent. The average income registered with tax authorities in 2010 was 17,241 euros but by 2015, it had dropped to 12,133 euros, with all types of income-earners, from salaried employees to pensioners and farmers, deeply affected.

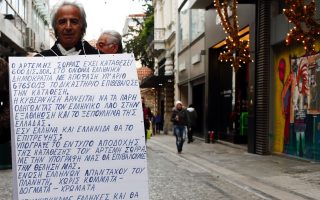

It is a reminder of the cost, at a national and personal level, involved in producing Greece’s dramatic fiscal turnaround. When the country, or government, beats the targets it has been set, there are millions of stories of sacrifice, difficulty and pain behind these achievements.

They should remind us that this fiscal tail-chasing cannot be an end in itself. Nobody should be taking any great satisfaction from Greece beating its fiscal target by more than about eight times, as it did last year, because it is not a sustainable way to run a country and its economy. It is this somber thought that should dominate the discussions between Greece and its lenders in the next few weeks. They should not be encouraged by the numbers ELSTAT announced on Friday, but concerned.