Outgoing EWG chief says government expectations of a ‘clean exit’ unrealistic

A debt relief deal after the current bailout program expires in August will mean fresh commitments from Athens toward its international creditors and not a so-called “clean exit” as the government anticipates, outgoing Eurogroup Working Group (EWG) chief Thomas Wieser told Kathimerini on Sunday.

Even though the nature of Greece’s post-bailout relationship with the institutions is something that has not yet been discussed, Wieser notes that it will depend on what kind of agreement the two sides will reach for lightening the country’s debt pile, stressing that every bailed-out eurozone country has emerged with a different relationship with its creditors. Like Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Cyprus before it, he says, Greece will be under supervision until 75 percent of its debt is repaid, which, at current estimates, will be around 2060.

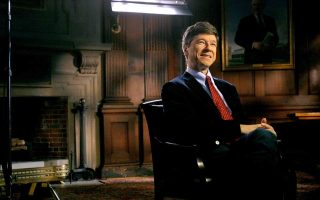

The 64-year-old Austrian economist retires at the end of the month, leaving behind what many analysts feel will be a vacuum after having being a key component in navigating the euro through the worst crises in its history at the helm of the Euro Working Group, the group of key finance ministry officials that meets once a month in Brussels to prepare their ministers’ gatherings, the Eurogroup meetings, since 2012.

Wieser’s job was to be the main negotiator and the glue between all the main actors of the adjustment programs that were implemented in Greece, Ireland, Spain, Cyprus and Portugal, striking deals at the last minute, bringing these economies back from the brink when everybody had lost their faith and their patience, and ensuring that the euro survived its greatest crisis yet.

Do you feel that Brussels was asleep at the wheel in 2009 when the Greek crisis started? Were there signs that things were out of control back then?

I think that things were not acted upon much, much earlier. A colleague of mine in Vienna in 2007 or so said that he was very suspicious about the Greek economy, that “there is a black hole” in the Greek financial statistics. He was in the Finance Ministry and was looking into international finance accounts and said “there is something that doesn’t add up.” The next time I was in Brussels I spoke to the director-general of ECOFIN, Marco Buti, and said, “We think there is a black hole in the Greek statistics; maybe you should look into that,” but nothing ever happened. That was 2007.

So when the crisis began in 2009 and the real deficit was revealed were people in Brussels shocked or do you feel they already knew the situation?

Of course it was a shock because in reality hardly anybody knew. I talked to statisticians later and they said, “Of course, because the member-states never allowed us to look into their financial accounts, at the statistics of the member-states.” It was only over the course of the crisis that the rules changed.

Former Greek finance minister Giorgos Papaconstantinou said he had asked for help many times after the crisis emerged but got little response from Europe other than “Take more measures and we’ll see how it goes.” Why did it take the Europeans so long to act?

I think it was largely a problem that we were totally unprepared for this. The whole architecture of the monetary union, the Maastricht Treaty was built on an assumption which turned out to be wrong: that there could be no destabilizing current account deficit in a monetary union; that capital markets could not dry up. All of that happened and there was a non-bailout clause in the treaty, which quite a lot of people were pointing at and saying, “What the hell are we going to do?” That was the situation Papaconstantinou was faced with. The policies were not in place and the treaty architecture more or less forbade us to do what we had to do, so we had to invent things in a couple of years in the midst of a crisis – instruments, processes and procedures – and we had to educate politicians, national parliaments and national audiences all of that. Now we are better prepared.

The monetary union as it was built in the 90s was incomplete and it could be destabilized by individual asymmetric shocks such as the fiscal shock or competitive shocks we had in Greece, Portugal, Cyprus and Spain. Previously, before the crisis, there was the strong belief that these things won’t happen. A large part of the blame lay with US monetary policy in the 90s and the feeling of complacency at the start of the millennium that things were under control and policy was pushing and pulling the right levers, that growth was here to stay, that people were affluent and globalization was benign for everybody. Greece had the Olympics and I think that’s when things started going wrong for it. I’m not totally serious about the Olympics but the spending spree of the Olympic-related infrastructures was also hiding other cost overruns. Saying that the Greek crisis was a fiscal crisis is, of course, not correct. A fiscal crisis is the superficial manifestation of underlying problems.

What do you think is at the root of the Greek crisis?

First and foremost there is a governance issue; that relationships count for more than quality and efficiency.

Clientelism?

Exactly. Segmented groups of society, on both sides of the political spectrum, enterprises and trade unions, have simply carved up the economy into very cushy jobs. Those who are not inside this comfortable cocoon find it very difficult to defend themselves, be they enterprises or citizens. People felt inclined to hire thousands of people at state-owned enterprises where they don’t need them – it was a business model. You can only retain this model if you try to close your economy to foreign competition, since foreign competition is very bad to such a business model. That in turn makes the economy less and less competitive.

What you describe doesn’t seem to have changed much eight years after the crisis started. Do you feel we have overcome these main issues?

No. Greece is not completely past that point. But no country gets completely over that. There are established interests. The more meritocratic a society is, the easier it is to overcome these dangers.

We have been through eight years of program reforms and Greeks have lost 25 percent of their income. Do you think their loss is equal to the reforms that have been implemented?

If you look at the loss of income in Greece you have to ask yourself whether the income level and GDP level that Greece had attained from all these deficits was sustainable. In 2009 Greece was pumping more than 15 percent of GDP as deficit additional to the economy. If one believes that government spending has an effect on the level of economy then you must wonder what the level of income and GDP in Greece would have been if the Greek government had pursued a more sane, sustainable fiscal policy.

Was there a problem in the design of all three programs?

I think compared to the overall problems that Greece had it was more fiscally oriented than it would have been if a perfect Greek government had designed a reform program by itself. If you do a program from the outside you have to work with levers that work in the short run. That is fiscal. A good and responsible government thinks of the long term. And in the very long term you need to fix institutions and build up a meritocratic society. If you are running out of money you have to fix things immediately. If a water pipe breaks you don’t think how to fix it as beautifully as possible but bring the cheapest plumber to get rid of the water.

That may be the case for the first program but not the third. We say that Greeks design the program, but we all know that it is under the control of the Europeans and International Monetary Fund.

After every program the IMF would say that we have focused too much on too many small things and next time it was going to do it differently. The degree to which this happens depends on how cooperative the relationship with the government is. The more one has the feeling that it is doing this together with the government, the more one can concentrate on a few high-level principles and high actions because there is the presumption that the government will be doing the right things anyway. This is how it happened in Spain or Ireland.

In Greece it was always antagonistic. The institutions and the member-states were always seen as the “xenos,” not as somebody to solve the problem together with. Because of that very antagonistic attitude, lots of things never got done as agreed; that’s why it became so micro-economic and evasive. We did that much less in other countries.

Who pushed for the IMF involvement in the Greek program? Looking back, was it a mistake?

I think it was good to have the IMF with European Commission and the ECB involved, but if we were to say one of these institutions should not have been on board we don’t know how the others would be involved. To put it differently, if the IMF had not been on board maybe the European Commission would be totally different from what it was. We will never know. We all made our fair share of mistakes.

What was your biggest mistake?

I should have realized much earlier the degree to which a debt restructuring for Greece was necessary, at the beginning of the first program.

Would things have been different?

If we had a debt restructuring and more cooperative Greek counterparts, then many, many things would have been different. We had to learn the hard way. If we had everything prepared, if the ESM was in place, if we had all of these court of justice verdicts and the German constitution court verdicts all in place, then we could proceed with debt restructuring at the beginning and it would have been much easier.

In 2012, when the possibility of Grexit first appeared, you start drafting a plan Z, as it was called. What was the feeling in Berlin?

There was a very strong feeling that risk was high, that Greece could exit and everybody wanted to be prepared for this situation. The plan was simply designed to make sure that not only the Greek economy but the economies of other member-states will be able to withstand a shock in as robust as possible a manner and this required preparations on monetary policy instruments to custom controls, border controls and humanitarian aid of course. But I would not focus everything on Berlin because there were quite a number of member-states who had limits on how much more they could do. Stop focusing on Berlin. There were a couple of other northern states who were in that camp. This came after quite some years of a very limited sense of cooperation with Greek authorities.

Was there a feeling of hopelessness, fatigue with Greece in 2012?

It was a strong feeling compared to other countries. There was no realization in the political class of what the problem was and it would appear saying that it was the fault of others. And if you look at any other country that had a program, there was a very strong process domestically, essentially saying what we did wrong. Greece is the only country where this process never happened and where there is a strong story line that it’s everybody else’s fault, especially the foreigner.

Conservative prime minister Antonis Samaras was elected in June 2012 and Merkel had still not decided if Greece should remain in the eurozone. When did that perception change?

There were a few conversations in mid-autumn 2012 which I think convinced major players that one should give another try with Greece in the euro area. I cannot say what everybody was thinking, but my impression is that for some people the negative impacts of Greece leaving the euro area played an important role.

Samaras was told by the Eurogroup in November 2012 that if he achieved a primary surplus he would be given debt relief. Why did this not happen?

The debt relief in 2014, if I remember correctly, was agreed to go ahead at the first review after a primary surplus had been reached. But as the Samaras government was not willing to conclude a review there was no debt relief. That is my recollection.

Was there a discussion at the end of 2014 that a new party was gaining momentum in Greece?

That’s where the politics of other member-states comes in. The Germans, Finns, Dutch, Slovaks and others had a feeling that the program has a certain volume, end date and certain conditions – and that if it’s over, it’s over. The Greek government was not doing the reforms under the program agreed because of upcoming elections, and everyone vastly preferred not to have a new program.

What we went through in 2015, with extension after extension, it was a joke. I don’t think the Greek government had any intention to do more in the extension period of extension than before. They were wasting our time.

Why do you say that?

Because one of the leaders of the government said this was their intention: to waste time so we would give the money anyway without doing anything. I told him, “Stop dreaming.”

What was former finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’s role in that period? Some say he cost Greece 80 billion euros. Could that be true?

If you calculate all the destruction of the capital value in the financial system, this is probably true. But I would not personalize it in that manner because it was not a one-man dictatorship. It was always argued that this was a collective decision.

When did the attitude change? When Varoufakis left?

I think that everybody felt the change the first five minutes that Euclid Tsakalotos talked to the Eurogroup. The difference was that with Euclid, one could find a solution. He was not looking for a pulpit to grandstand.

How significant was US involvement in the Greek program?

It was by far stronger than in any other program and I think that the Americans have been extremely knowledgeable and very helpful. Mainly in not being dogmatic but trying to push for a solution that was good for Greece and the eurozone as well. They obviously had very strong interests not because of the pure economics but because of geopolitical factors, which is an issue one has to be reminded of as well, as Europeans.

How would the US apply pressure?

They called everybody constantly. They were totally in the loop. All administrations were in constant and very good contact. People were constantly talking to each other at all levels, the highest level as well.

Trust toward the Greek government was lost completely in the summer of 2015. Do you feel it has recovered since?

It started from a fairly low level, even before elections. Trust in the quality of cooperation was very, very limited. After the election of 2015, it was less than zero. I think there is a strong trust among heads of state that Tsipras means what he says and the firm belief that he wants to deliver the program, exit the program and honor all agreements.

Are you confident we are going to finish the program in August with no further arrangements? How do you see the post-program situation evolving after August?

It remains to be discussed. It depends on what the arrangements at the end of the program are, arrangements on financing and debt relief, and how all this hangs together. If there should be further debt relief after the end of the program then it’s only logical that there will be some kind of additional agreements. There is an existing regulation that is enforced for Ireland, Spain Portugal, Cyprus, an enhanced surveillance until 75 percent of creditors have been repaid.

What does enhanced surveillance mean?

That depends on the economic and financial situation. If the risks are predominantly in the financial sector or fiscal, you have a more frequent and intensive monitoring by the institutions with a more structured and extensive discussion.

Do you fee that there is a gap between the numbers, which show a better situation in Greece, and what is actually happening in the economy?

I still have the feeling that foreign direct investment is not welcomed in Greece as it is in many other countries. I have the feeling that many domestic rules and regulations over the last eight years have changed but it’s true we haven’t seen a significant pickup in investment activity. I think it’s only very recent that there is some trust by national and international investors that Greece is finally approaching the time where it can stand on its own feet again financially and that it’s not a huge risk to invest in its economy. And with the state of Greece being what it was in the last years, no rational investor who had the choice of investing, did. Greece was considered too risky. I guess this is proof that something doesn’t just pop up when you sign a decree or a law but takes months and sometimes years until it is factored in investment decisions.

An important issue which we talked about with many member-states and Greece, is how certain can an investor be that he will get a fair and rapid legal procedure if he/she wants to access collateral, to get a rapid decision by an administrative entity, all of these things. We see huge differences in investment levels in countries where there is rapid and predictable legal proceeding versus other member-states where there is less rapid and predictable decision-making. This has a huge impact on investment levels, growth and employment.

Do you feel you should have focused more on these areas, the justice and maybe education systems?

I would agree that these issues matter most in the long run for the good development of the country. A high-class education system and a well-functioning judicial system are the cornerstones of an affluent and productive society, but this is the responsibility of a domestic government.

Isn’t it ironic when member-states spend so much money and time on Greece and one of the pillars doesn’t work, such as justice or education? Doesn’t the whole program lose purpose and value?

As I said before, the program is only the stepping stone from the very deep water to more shallow waters where a government stands on its own feet and does what needs to be done. It solves the short-term reversal of capital flows, it solves in the short term the fiscal issue if you lose access to capital markets and it can give an impetus to overcome the political impasse of a country as well while structural reforms are undertaken. But it cannot and should not be the instrument with which constitutional pillars of a country are changed. If one doesn’t have trust that the country is moving in the right direction, then one has to take these consequences nationally and not ask whoever is in the UN, NATO, IMF or Brussels to intervene in any country in the world where we think the educational system is not working or do not appreciate the quality of the judicial system.

Do you have the feeling that many prior actions have been passed though Parliament but not actually implemented? Such as the privatization of the former airport plot at Elliniko…

Elliniko is a very good example of why foreign investors are extremely doubtful of investing heavily in Greece across a variety of sectors and also shows how bureaucratic many administrative procedures are. Those are the true reforms that the country needs, cutting through all these processes.

What shocked you most when you started looking at Greece closer?

The absence of meritocratic decisions. I have many examples but I won’t tell you. I don’t know if it has improved. Very many people with good intentions are around but again and again these very good intentions are thwarted by reality.

Did you feel at any point that Greece would leave the eurozone?

Yes, after the summer 2015 referendum. I felt that it was over. I still don’t know what happened, no idea, maybe we totally misunderstood the intention of the referendum, I don’t know. It’s a mystery what happened and Tsipras changed his mind. Was it a Catholic enlightenment? We will never know.

Are there any unsung heroes or villains in the Greek crisis?

Whether you are a villain or not is very subjective. For me the villain is one who is acting in his own interest, not for his country or institution. For me there are two people without whom things would not have happened like this: One is [former Eurogroup chief] Jeroen Dijsselbloem and the other one is Alternate Finance Minister Giorgos Houliarakis. Dijsselbloem is so clever and patient and empathic and socially skilled, that he is the only one who could have pulled all these different elements together and come to a solution which led Greece to start growing again in the euro area. And without Houliarakis, transmission of what people outside Greece were thinking into Greece would never had functioned.

What was the biggest mistake the Europeans made in Greece?

One large mistake was simply in the setup of the troika. We should have designed something different. It was too antagonistic, with too many different institutions, specifics, jealousies and aims. The most efficient would have been to have one institution – but which one?